- Open access

- Published: 05 January 2021

The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis

- Haroon Rasool ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0083-4553 1 ,

- Shafat Maqbool 2 &

- Md. Tarique 1

Future Business Journal volume 7 , Article number: 1 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

122k Accesses

94 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

Tourism has become the world’s third-largest export industry after fuels and chemicals, and ahead of food and automotive products. From last few years, there has been a great surge in international tourism, culminates to 7% share of World’s total exports in 2016. To this end, the study attempts to examine the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth by using the panel data over the period 1995–2015 for five BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries. The results of panel ARDL cointegration test indicate that tourism, financial development and economic growth are cointegrated in the long run. Further, the Granger causality analysis demonstrates that the causality between inbound tourism and economic growth is bi-directional, thus validates the ‘feedback-hypothesis’ in BRICS countries. The study suggests that BRICS countries should promote favorable tourism policies to push up the economic growth and in turn economic growth will positively contribute to international tourism.

Introduction

World Tourism Day 2015 was celebrated around the theme ‘One Billion Tourists; One Billion Opportunities’ highlighting the transformative potential of one billion tourists. With more than one billion tourists traveling to an international destination every year, tourism has become a leading economic sector, contributing 9.8% of global GDP and represents 7% of the world’s total exports [ 59 ]. According to the World Tourism Organization, the year 2013 saw more than 1.087 billion Foreign Tourist Arrivals and US $1075 billion foreign tourism receipts. The contribution of travel and tourism to gross domestic product (GDP) is expected to reach 10.8% at the end of 2026 [ 61 ]. Representing more than just economic strength, these figures exemplify the vast potential of tourism, to address some of the world´s most pressing challenges, including socio-economic growth and inclusive development.

Developing countries are emerging as the important players, and increasingly aware of their economic potential. Once essentially excluded from the tourism industry, the developing world has now become its major growth area. These countries majorly rely on tourism for their foreign exchange reserves. For the world’s forty poorest countries, tourism is the second-most important source of foreign exchange after oil [ 37 ].

The BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) countries have emerged as a potential bloc in the developing countries which caters the major tourists from developed countries. Tourism becomes major focus at BRICS Xiamen Summit 2017 held in China. These countries have robust growth rate, and are focal destinations for global tourists. During 1990 to 2014, these countries stride from 11% of the world’s GDP to almost 30% [ 17 ]. Among BRICS countries, China is ranked as an important destination followed by Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa [ 60 ].

The importance of inbound tourism has grown exponentially, because of its growing contribution to the economic growth in the long run. It enhances economic growth by augmenting the foreign exchange reserves [ 38 ], stimulating investments in new infrastructure, human capital and increases competition [ 9 ], promoting industrial development [ 34 ], creates jobs and hence to increase income [ 34 ], inbound tourism also generates positive externalities [ 1 , 14 ] and finally, as economy grows, one can argue that growth in GDP could lead to further increase in international tourism [ 11 ].

The tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) proposed by Balaguer and Cantavella-Jorda [ 3 ], states that expansion of international tourism activities exerts economic growth, hence offering a theoretical and empirical link between inbound tourism and economic growth. Theoretically, the TLGH was directly derived from the export-led growth hypothesis (ELGH) that postulates that economic growth can be generated not only by increasing the amount of labor and capital within the economy, but also by expanding exports.

The ‘new growth theory,’ developed by Balassa [ 4 ], suggests that export expansion can trigger economic growth, because it promotes specialization and raises factors productivity by increasing competition, creating positive externalities by advancing the dispersal of specialized information and abilities. Exports also enhance economic growth by increasing the level of investment. International tourism is considered as a non-standard type of export, as it indicates a source of receipts and consumption in situ. Given the difficulties in measuring tourism activity, the economic literature tends to focus on primary and manufactured product exports, hence neglecting this economic sector. Analogous to the ELGH, the TLGH analyses the possible temporal relationship between tourism and economic growth, both in the short and long run. The question is whether tourism activity leads to economic growth or, alternatively, economic expansion drives tourism growth, or indeed a bi-directional relationship exists between the two variables.

To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. Financial markets are considered a key factor in producing strong economic growth, because they contribute to economic efficiency by diverting financial funds from unproductive to productive uses. The origin of this role of financial development may is traced back to the seminal work of Schumpeter [ 50 ]. In his study, Schumpeter points out that the banking system is the crucial factor for economic growth due to its role in the allocation of savings, the encouragement of innovation, and the funding of productive investments. Early works, such as Goldsmith [ 18 ], McKinnon [ 39 ] and Shaw [ 51 ] put forward considerable evidence that financial development enhances growth performance of countries. The importance of financial development in BRICS economies is reflected by the establishment of the ‘New Development Bank’ aimed at financing infrastructure and sustainable development projects in these and other developing countries. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no attempt has been made so far to investigate the long-run relationship Footnote 1 between tourism, financial development and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Hence, the present study is an attempt to fill the gap in the existing literature.

Review of past studies

From last few decades there has been a surge in the research related to tourism-growth nexus. The importance of growth and development and its determinants has been studied extensively both in developed and developing countries. Extant literature has recognized tourism as an important determinant of economic growth. The importance of tourism has grown exponentially, courtesy to its manifold advantages in form of employment, foreign exchange production household income and government revenues through multiplier effects, improvements in the balance of payments and growth in the number of tourism-promoted government policies [ 21 , 41 , 53 ]. Empirical findings on tourism and economic development have produced mixed finding and sometimes conflicting results despite the common choice of time series techniques as a research methodology. On empirical grounds, four hypotheses have been explored to determine the link between tourism and economic growth [ 12 ]. The first two hypotheses present an account on the unidirectional causality between the two variables, either from tourism to economic growth (Tourism-led economic growth hypothesis-TLGH) or its reserve (economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis-EDTH). The other two hypotheses support the existence of bi-directional hypothesis, (bi-directional causality hypothesis-BC) or that there is no relationship at all (no causality hypothesis-NC), respectively. According to TLEG hypothesis, tourism creates an array of benefits which spillover though multiple routes to promote the economic growth [ 55 ]. In particular, it is believed that tourism (1) increases foreign exchange earnings, which in turn can be used to finance imports [ 38 ], (2) it encourages investment and drives local firms toward greater efficiency due to the increased competition [ 3 , 31 ], (3) it alleviates unemployment, since tourism activities are heavily based on human capital [ 10 ] and (4) it leads to positive economies of scale thus, decreasing production costs for local businesses [ 1 , 14 ]. Other recent studies which find evidence in favor of the TLGH hypothesis include [ 44 , 52 ]. Even though literature is dominated by TLGH, few studies produce a result in support of EDTH [ 40 , 41 , 45 ]. Payne and Mervar [ 45 ] posit that tourism growth of a country is mobilized by the stability of well-designed economic policies, governance structures and investments in both physical and human capital. This positive and vibrant environment creates a series of development activities which proliferate and flourish the tourism. Pertaining to the readily available information, bi-directional causality could also exist between tourism income and economic growth [ 34 , 49 ]. From a policy view, a reciprocal tourism–economic growth relationship implies that government agendas should cater for promoting both areas simultaneously. Finally, there are some studies that do not offer support to any of the aforementioned hypotheses, suggesting that the impact between tourism and economic growth is insignificant [ 25 , 47 , 57 ]. There is a vast literature examining the relationship between tourism and growth as a result, only a selective literature review will be presented here.

Banday and Ismail [ 5 ] used ARDL cointegration model to test the relationship between tourism revenue and economic growth in BRICS countries from the time period of (1995–2013). The study validates the tourism-led growth hypothesis for BRICS countries, which evinces that tourism has positive influence on economic growth.

Savaş et al. [ 54 ] evaluated the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the context of Turkey. The study employed gross domestic product, real exchange rate, real total expenditure and international tourism arrivals to sketch out the causality among variables. The result reveals a unidirectional relationship between tourism and real exchange rate. The findings suggest that tourism is the driving force for economic growth, which in turn helps turkey to culminate its current account deficit.

Dhungel [ 15 ] made an effort to investigate causality between tourism and economic growth, In Nepal for the period of (1974–2012), by using Johansen’s cointegration and Error correction model. The result states that unidirectional causality exists in the long run, while in short run no causality exists between two constructs. The study emphasized that strategies should be devised to attain causality running from tourism to economic growth.

Mallick et al. [ 36 ] analyzed the nexus between economic growth and tourism in 23 Indian states over a period of 14 years (1997–2011). Using panel autoregressive distributed lag model based on three alternative estimators such as mean group estimator, pooled mean group and dynamic fixed effects, Research found that tourism exerts positive influence on economic growth in the long run.

Belloumi [ 8 ] examines the causal relationship between international tourism receipts and economic growth in Tunisia by using annual time series data for the period 1970–2007. The study uses the Johansen’s cointegration methodology to analyze the long-run relationship among the concerned variables. Granger causality based Vector error correction mechanism approach indicates that the revenues generated from tourism have a positive impact on economic growth of Tunisia. Thus, the study supports the hypothesis of tourism-driven economic growth, which is specific to developing countries that base their foreign exchange earnings on the existence of a comparative advantage in certain sectors of the economy.

Tang et al. [ 58 ] explored the dynamic Inter-relationships among tourism, economic growth and energy consumption in India for the period 1971–2012. The study employed Bounds testing approach to cointegration and generalized variance decomposition methods to analyze the relationship. The bounds testing and the Gregory-Hansen test for cointegration with structural breaks consistently reveals that energy consumption, tourism and economic growth in India are cointegrated. The study demonstrated that tourism and economic growth have positive impact on energy consumption, while tourism and economic growth are interrelated; with tourism exert significant influence on economic growth. Consequently, this study validates the tourism-led growth hypothesis in the Indian context.

Kadir and Karim [ 24 ]) examined the causal nexus between tourism and economic growth in Malaysia by applying panel time series approach for the period 1998–2005. By applying Padroni’s panel cointegration test and panel Granger causality test, the result indicated both short and long-run relationship. Further, the panel causality shows unidirectional causality directing from tourism receipts to economic growth. The result provides evidence of the significant contribution of tourism industry to Malaysia’s economic growth, thereby justifying the necessity of public intervention in providing tourism infrastructure and facilities.

Antonakakis et al. [ 2 ] test the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe by using a newly introduced spillover index approach. Based on monthly data for 10 European countries over the period 1995–2012, the findings suggested that the tourism–economic growth relationship is not stable over time in terms of both magnitude and direction, indicating that the tourism-led economic growth (TLEG) and the economic-driven tourism growth (EDTG) hypotheses are time-dependent. Thus, the findings of the study suggest that the same country can experience tourism-led economic growth or economic-driven tourism growth at different economic events.

Oh [ 41 ] verifies the contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy by applying Engle and Granger two-stage approach and a bivariate Vector Autoregression model. He claimed that economic expansion lures tourists in the short run only, while there is no such long-run stable relationship between international tourism and economic development in Korea.

Empirical studies have pronouncedly focused on the literature that tourism promotes economic growth. To further substantiate the nexus, the study will investigate the plausible linkages between economic growth and international tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. The inclusion of financial development in the examination of tourism-growth nexus is a unique feature of this study, which have an influencing role in economic growth as financial development has been theoretically and empirically recognized as source of comparative advantage [ 22 ].

This study employs panel ARDL cointegration approach to verify the existence of long-run association among the variables. Further, study estimated the long-run and short-run coefficients of the ARDL model. Subsequently, Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] panel Granger causality test has been employed to check the direction of causality between tourism, financial development and economic growth among BRICS countries.

Database and methodology

Data and variables.

The study is analytical and empirical in nature, which intends to establish the relationship between economic growth and inbound tourism in BRICS countries. For the BRICS countries, limited studies have been conducted depicting the present scenario. Therefore, present study tries to verify the relevance of tourism in economic growth to further enhance the understanding of economic dynamics in BRICS countries. The data used in the study are annual figures for the period stretching from 1995 to 2015, consisting of one endogenous variable (GDP per capita, a proxy for economic growth) and two exogenous variables (international tourism receipts per capita and financial development). The variables employed in the study are based on the economic growth theory, proposed by Balassa [ 4 ], which states that export expansion has a relevant contribution in economic growth. Further, this study incorporates financial development in the model to reduce model misspecification as it is considered to have an influencing role in economic growth both theoretically and empirically [ 22 , 33 ].

The annual data for all the variables have been collected from the World Development Indicators (WDI, 2016) database. The variables used in the study includes gross domestic product per capita (GDP) in constant ($US2010) used as a proxy for economic growth (EG), international tourism receipts per capita (TR) in current US$ as it is widely accepted that the most adequate proxy of inbound tourism in a country is tourism expenditure normally expressed in terms of tourism receipts [ 32 ] and financial development (FD). In line with a recent study on the relationship between financial development and economic growth by Hassan et al. [ 19 ], financial development is surrogated by the ratio of the broad money (M3) to real GDP for all BRICS countries. Here we use the broadest definition of money (M3) as a proportion of GDP– to measure the liquid liabilities of the banking system in the economy. We use M3 as a financial depth indicator, because monetary aggregates, such as M2 or M1, may be a poor proxy in economies with underdeveloped financial systems, because they ‘are more related to the ability of the financial system to provide transaction services than to the ability to channel funds from savers to borrowers’ [ 26 ]. A higher liquidity ratio means higher intensity in the banking system. The assumption here is that the size of the financial sector is positively associated with financial services [ 29 ]. All the variables have been taken into log form.

Unit root test

To verify the long-run relationship between tourism and economic growth through Bounds testing approach, it is necessary to test for stationarity of the variables. The stationarity of all the variables can be assessed by different unit root tests. The study utilizes panel unit root test proposed by Levin et al. [ 35 ] henceforth LLC and Im et al. [ 23 ] henceforth IPS based on traditional augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test. The LLC allows for heterogeneity of the intercepts across members of the panel under the null hypothesis of presence of unit root, while IPS allows for heterogeneity in intercepts as well as in the slope coefficients [ 48 ].

Panel ARDL approach to Cointegration

After checking the stationarity of the variables the study employs panel ARDL technique for Cointegration developed by Pesaran et al. [ 23 ]. Pesaran et al. [ 23 ] have introduced the pooled mean group (PMG) approach in the panel ARDL framework. According to Pesaran et al. [ 23 ], the homogeneity in the long-run relationship can be attributed to several factors such as arbitration condition, common technologies, or the institutional development which was covered by all groups. The panel ARDL bounds test [ 46 ] is more appropriate by comparing other cointegration techniques, because it is flexible regarding unit root properties of variables. This technique is more suitable when variables are integrated at different orders but not I (2). Haug [ 20 ] has argued that panel ARDL approach to cointegration provides better results for small sample data set such as in our case. The ARDL approach to cointegration estimates both long and short-run parameters and can be applied independently of variable order integration (independent of whether repressors are purely I (0), purely I(1) or combination of both. The ARDL bounds test approach used in this study is specified as follows:

where Δ is the first-difference operator, \(\alpha_{0}\) stands for constant, t is time element, \(\omega_{1} , \omega_{2} \;\;{\text{and}}\;\; \omega_{3}\) represent the short-run parameters of the model, \(\emptyset_{1} , \emptyset_{2} ,and \emptyset_{3}\) are long-run coefficients, while \(V_{it}\) is white noise error term and lastly, it represents country at a particular time period. In the ARDL model, the bounds test is applied to determine whether the variables are cointegrated or not.

This test is based on the joint significance of F -statistic and the χ 2 statistic of the Wald test. The null hypothesis of no cointegration among the variables under study is examined by testing the joint significance of the F -statistic of \(\omega_{1} , \omega_{2} ,\omega_{3}\) .

In case series variables are cointegrated, an error correction mechanism (ECM) can be developed as Eq. ( 2 ), to assess the short-run influence of international tourism and financial development on economic growth.

where ECT is the error correction term, and \(\varPhi\) is its coefficient which shows how fast the variables attain long-term equilibrium if there is any deviation in the short run. The error correction term further confirms the existence of a stable long-run relationship among the variables.

Panel granger causality test

To examine the direction of causality Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] test is employed. Instead of pooled causality, Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] proposed a causality based on the individual Wald statistic of Granger non-causality averaged across the cross section units. Dumitrescu and Hurlin [ 16 ] assert that traditional test allows for homogeneous analysis across all panel sets, thereby neglecting the specific causality across different units.

This approach allows heterogeneity in coefficients across cross section panels. The two statistics Wbar-statistics and Zbar-statistics provides standardized version of the statistics and is easier to compute. Wbar-statistic, takes an average of the test statistics, while the Zbar-statistic shows a standard (asymptotic) normal distribution.

They proposed an average Wald statistic that tests the null hypothesis of no causality in a panel subgroup against an alternative hypothesis of causality in at least one panel. Following equations will be used to check the direction of causality between the variables.

Estimation, results and Discussion

Descriptive statistics.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics of variables selected for the period 1995–2015. The variable set includes GDP, FD and TR for all BRICS countries. Brazil tops the list with GDP per capita of 4.18, while India lagging behind all BRICS nations. In the recent economic survey by International Monetary Fund (IMF report 2016), India was ranked 126 for its per capita GDP. India’s GDP per capita went up to $7170 against all other BRICS countries which were placed in the above $10,000 bracket. China has the highest tourism receipts in comparison to other BRICS countries. China is a very popular country for foreign tourists, which ranks third after France and USA. In 2014, China invested $136.8 billion into its tourist infrastructure, a figure second only to the United States ($144.3 billion). Tourism, based on direct, indirect, and induced impact, accounted for near 10% in the GDP of China (WTTC report 2017).

Stationarity results

Primarily, we employed LLC and IPS unit root test to assess the integrated properties of the series. The results of IPS and PP tests are presented in Table 2 . Panel unit root test result evinces that FD and TR are stationary at level, while GDP per capita is integrated variable of order 1. The result exemplifies that GDP per capita, Tourism receipts and Financial Development are integrated at 1(0) and 1(1). Consequently, the panel ARDL approach to cointegration can be applied.

Cointegration test results

In view of the above results with a mixture of order integration, the panel ARDL approach to cointegration is the most appropriate technique to investigate whether there exists a long-run relationship among the variables [ 42 ]. Table 3 illustrates that the estimated value of F-statistics, which is higher than the lower and upper limit of the bound value, when InEG is used as a dependent variable. Hence, we reject the null hypothesis of no cointegration \(H_{0 } : \emptyset_{1} = \emptyset_{2} = \emptyset_{3} = 0\) of Eq. ( 1 ). Therefore, the result asserts that international tourism, financial development and economic growth are significantly cointegrated over the period (1995–2015).

Subsequently, the study investigates the long-run and short-run impact of international tourism and financial development on economic growth. Lag length is selected on the principle of minimum Bayesian information criterion (SBC) value, which is 2 in our case. The long-run coefficients of financial development and tourism receipts with respect to economic growth in Table 4 indicate that tourism growth and financial development exerts positive influence on economic growth in the long run. In other words, an increase in volume of tourism receipts per capita and financial depth spurs economic growth and both the coefficients are statistically significant in case of BRICS nations in the long run. The results are interpreted in detail as below:

The elasticity coefficient of economic growth with respect to tourism shows that 1% rise in international tourism receipts per capita would imply an estimated increase of almost 0.31% domestic real income in the long run, all else remaining the same. Thus, the earnings in the form of foreign exchange from international tourism affect growth performance of BRICS nations positively. This finding of our study is in consonance with the empirical results of Kreishan for Jordan [ 30 ], Balaguer and Cantavella-Jordá [ 3 ] for Spain and Ohlan [ 43 ] for India.

Further our finding lend support to the wide applicability of the new growth theory proposed by Balassa which states that export expansion promote growth performance of nations. Thus, validates TLGH coined by Balaguer and Cantavell-Jorda [ 3 ] which states that inbound tourism acts a long-run economic growth factor. The so called tourism-led growth hypothesis suggests that the development of a country’s tourism industry will eventually lead to higher economic growth and, by extension, further economic development via spillovers and other multiplier effects.

Likewise, financial development as expected is found to be positively associated with economic growth. The coefficient of financial development states that 1% improvement in financial development will push up economic growth by 0.22% in the long run, keeping all other variables constant. The empirical results are consistent with the finding of Hassan et al. [ 19 ] for a panel of South Asian countries. Well-regulated and properly functioning financial development enhances domestic production through savings, borrowings & investment activities and boosts economic growth. Further, it promotes economic growth by increasing efficiency [ 7 ]. Levine [ 33 ] believes that financial intermediaries enhance economic efficiency, and ultimately growth, by helping allocation of capital to its best use. Modern growth theory identifies two specific channels through which the financial sector might affect long-run growth; through its impact on capital accumulation and through its impact on the rate of technological progress. The sub-prime crisis which depressed the economic growth worldwide in 2007 further substantiates the growth-financial development nexus.

In the third and final step of the bounds testing procedure, we estimate short-run dynamics of variables by estimating an error correction model associated with long-run estimates. The empirical finding indicates that the coefficient of error correction term (ECT) with one period lag is negative as well as statistically significant. This finding further substantiates the earlier cointegration results between tourism, financial development and economic growth, and indicates the speed of adjustment from the short-run toward long-run equilibrium path. The coefficient of ECT reveals that the short-run divergences in economic growth from long-run equilibrium are adjusted by 43% every year following a short-run shock.

The short-run parameters in Table 5 demonstrates that tourism and financial development acts as an engine of economic growth in the short run as well. The coefficient of both tourism receipts per capita and financial development with one period lag is also found to be progressive and significant in the short run. These results highlight the role of earnings from international tourism and financial stability as an important driving force of economic growth in BRICS nations in the short run as well.

Further, a comparison between short-run and long-run elasticity coefficients evince that long-run responsiveness of economic growth with respect to tourism and financial development is higher than that of short run. It exemplifies that over time higher international tourism receipts and well-regulated financial system in BRICS nations give more boost to economic growth.

Analysis of causality

At this stage, we investigate the causality between tourism, financial development and economic growth presented in Table 6 . The result shows bi-directional causal relationship between tourism and economic growth, thereby validates ‘feedback hypothesis’ and consequently supported both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) and its reciprocal, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTH). The bi-directional causality between inbound tourism and GDP, which directs the level of economic activity and tourism growth, mutually influences each other in that a high volume of tourism growth leads to a high level of economic development and reverse also holds true. These results replicate the findings of Banday and Ismail [ 5 ] in the context of BRICS countries, Yazdi et al. [ 27 ] for Iran and Kim et al. [ 28 ] for Taiwan. One of the channels through which tourism spurs economic growth is through the use of receipts earned in the form of foreign currency. Thus, growth in foreign earnings may allow the import of technologically advances goods that will favor economic growth and vice versa. Thus, results demonstrate that international tourism promotes growth and in turn economic expansion is necessary for tourism development in case of BRICS countries. With respect to policy context, this finding suggests that the BRICS nations should focus on economic policies to promote tourism as a potential source of economic growth which in turn will further promote tourism growth.

Similarly, in case of economic growth and financial development, the findings demonstrate the presence of bi-directional causality between two constructs. The findings validate thus both ‘demand following’ and supply leading’ hypothesis. The findings suggests that indeed financial development plays a crucial role in promoting economic activity and thus generating economic growth for these countries and reverse also holds. Our findings are in line with Pradhan [ 48 ] in case of BRICS countries and Hassan et al. [ 19 ] for low and middle-income countries. This suggests that finance development can be used as a policy variable to foster economic growth in the five BRICS countries and vice versa. The study emphasizes that the current economic policies should recognize the finance-growth nexus in BRICS in order to maintain sustainable economic development in the economy. The empirical results in this paper are in line with expectations, confirming that the emerging economies of the BRICS are benefiting from their finance sectors.

Finally, two-sided causal relationship is found between tourism receipts and financial development. That is, tourism might contribute to financial development and, in return, financial development may positively contribute to tourism. This means that financial depth and tourism in BRICS have a reinforcing interaction. The positive impact of tourism on financial development can be attributed to the fact that inflows of foreign exchange via international tourism not only increases income levels but also leads to rise in official reserves of central banks. This in turn enables central banks to adapt expansionary monetary policy. The positive contribution of financial sector to tourism is further characterized by supply leading hypothesis. Further, better financial and market conditions will attract tourism entrepreneurship, because firms will be able to use more capital instead of being forced to use leveraging [ 13 ]. Hence, any shocks in money supply could adversely affect tourism industry in these countries. Song and Lin [ 56 ] found that global financial crisis had a negative impact on both inbound and outbound tourism in Asia. This result is in consistent with Başarir and Çakir [ 6 ] for Turkey and four European countries.

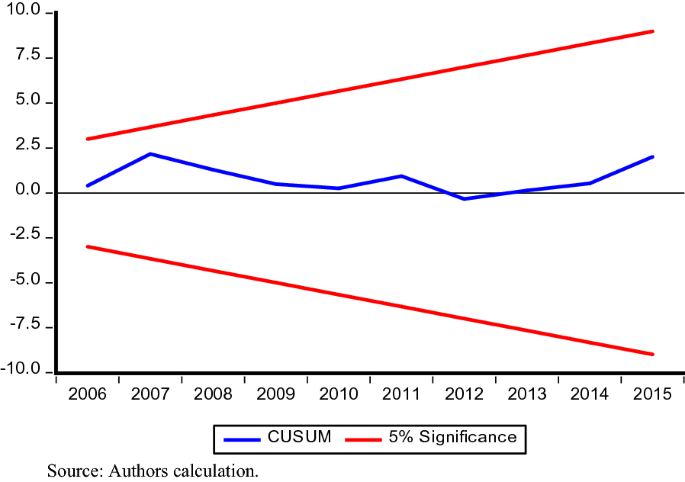

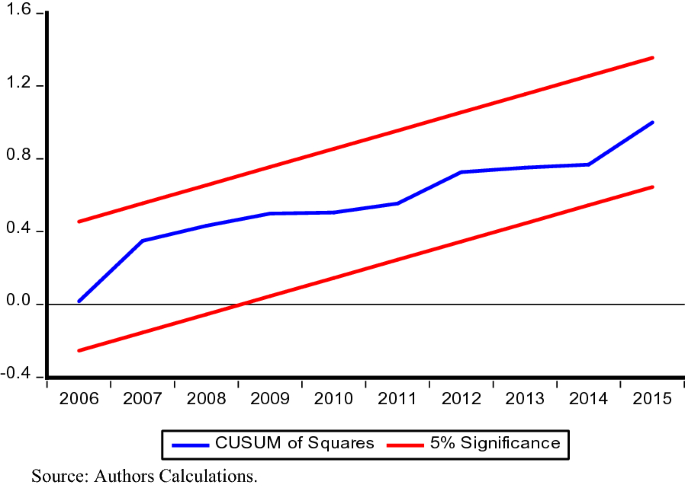

Stability tests

In addition, to test the stability of parameters estimated and any structural break in the model CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests are employed. Figs. 1 and 2 show blue line does not transcend red lines in both the tests, thus provides strong evidence that our estimated model is fit and valid policy implications can be drawn from the results.

Plot of CUSUM

Plot of CUSUMQ

Summary and concluding remarks

A rigorous study of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, through the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) perspective has remained a debatable issue in the economic growth literature. This study aims to empirically investigate the relationship between inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth in BRICS countries by utilizing the panel data over the period 1995–2015. The study employs the panel ARDL approach to cointegration and Dumitrescu-Hurlin panel Granger causality test to detect the direction of causation.

To the best of authors’ knowledge, this is the first study which explored the relationship between economic growth and tourism while considering the relative importance of financial development in the context of BRICS nations. The empirical results of ARDL model posits that in BRICS countries inbound tourism, financial development and economic growth are significantly cointegrated, i.e., variables have stable long-run relationship. This methodology has allowed obtaining elasticities of economic growth with respect to tourism and financial development both in the long run and short run. The result reveals that international tourism growth and financial development positively affects economic growth both in the long run and short run. The coefficient of tourism indicates that with a 1% rise in tourism receipts per capita, GDP per capita of BRICS economies will go up by 0.31% in the long run. This finding lends support to TLGH coined by Balaguer and Cantavell-Jorda [ 3 ] which states that inbound tourism acts a long-run economic growth factor. The so called tourism-led growth hypothesis suggests that the development of a country’s tourism industry will eventually lead to higher economic growth and, by extension, further economic development via spillovers and other multiplier effects.

Likewise, 1% improvement in financial development, on average, will increase economic growth in BRICS countries by 0.22% in the long run. The result seems logical as modern growth theory identifies two channels through which the financial sector might affect long-run growth: first, through its impact on capital accumulation and secondly, through its impact on the rate of technological progress. The sub-prime crisis which hit the economic growth Worldwide in 2007 further substantiates the growth-financial development nexus.

The negative and statistically significant coefficient of lagged error correction term (ECT) further substantiates the long-run equilibrium relationship among variables. The negative coefficient of ECT also shows the speed of adjustment toward long-run equilibrium is 43% per annum if there is any short-run deviation. The estimates of parameters are found to be stable by applying CUSUM and CUSUMQ for the time period under consideration. Therefore, inbound tourism earnings and financial institutions can be used as a channel to increase economic growth in BRICS economies.

Further, Granger causality test result indicates the bi-directional causation in all cases. Hence, the causal relationship between international tourism and economic growth is bi-directional. And, consequently this empirical finding lends support to both the tourism-led growth hypothesis (TLGH) and its reciprocal, the economic-driven tourism growth hypothesis (EDTH). This means that tourism is not only an engine for economic growth, but the economic outcome on itself can play an important role in providing growth potential to tourism sector.

The Granger causality findings provide useful information to governments to examine their economic policy, to adjust priorities regarding economic investment, and boost their economic growth with the given limited resources. Thus, it is suggested that more resources should be allocated to tourism industry and tourism-related industries if the tourism-led growth hypothesis holds true. On the other side, if economic-driven tourism growth is supported then more resources should be diverted to leading industries rather than the travel and tourism sector, and the tourism industry will in turn benefit from the resulting overall economic growth. And, when bi-directional causality is detected, a balanced allocation of economic resources for the travel and tourism sector and other industries is important and necessary. The policy implication is that resource allocation supporting both the tourism and tourism-related industries could benefit both tourism development and economic growth.

To sum up, the major finding of this study lends support to wide applicability of the tourism-led growth hypothesis in case of BRICS countries. Thus, in the Policy context, significant impact of tourism on BRICS economy rationalizes the need of encouraging tourism. Tourism can spur economic prosperity in these countries and for this reason; policymakers should give serious consideration toward encouraging tourism industry or inbound tourism. BRICS countries should focus more on tourism infrastructure, such as, convenient transportation, alluring destinations, suitable tax incentives, viable hostels and proper security arrangements to attract the potential tourists. Most of these countries are devoid of rich facilities and popular tourist incentives, to get promoted as important destination and in the long-run promotes economic growth. Further, they need a staunch support from all sections of authorities, non-government organizations (NGOs), and private and allied industries, in the endeavor to attain sustainable growth in tourism. Both state and non-state actors must recognize this growing industry and its positive implication on economy.

For future research, we suggest that researchers should consider the nonlinear factor in the dynamic relationship of tourism and economic growth in case of BRICS countries. Further one can go for comparative study to examine the TLGH in BRICS countries.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in the study can be provided by the corresponding author on request.

There are no fixed definitions of short, medium and long run and generally in macroeconomics, short run can be viewed as 1 to 2 or 3 years, medium up to 5 years and long run from 5 years to 20 or 25 years.

Abbreviations

autoregressive distributed lag model

Brazil, Russia, India, China and South-Africa

United Nations World Tourism Organization

World Travel & Tourism Council

gross domestic product

world development indicators

tourism-led growth hypothesis

export-led growth hypothesis

economic-driven tourism hypothesis

augmented Dickey–Fuller test

error correction model

error correction term

Andriotis K (2002) Scale of hospitality firms and local economic development—evidence from Crete. Tourism Manag 23(4):333–341

Google Scholar

Antonakakis N, Dragouni M, Filis G (2015) How strong is the linkage between tourism and economic growth in Europe? Econ Modell 44:142–155

Balaguer J, Cantavella-Jorda M (2002) Tourism as a long-run economic growth factor: the Spanish case. Appl Econ 34(7):877–884

Balassa B (1978) Exports and economic growth: further evidence. J Dev Econ 5(2):181–189

Banday UJ, Ismail S (2017) Does tourism development lead positive or negative impact on economic growth and environment in BRICS countries? A panel data analysis. Econ Bull 37(1):553–567

Basarir C, Çakir YN (2015) Causal interactions between CO 2 emissions, financial development, energy and tourism. Asian Econ Financ Rev 5(11):1227

Bell C, Rousseau PL (2001) Post-independence India: a case of finance-led industrialization? J Dev Econ 65(1):153–175

Belloumi M (2010) The relationship between tourism receipts, real effective exchange rate and economic growth in Tunisia. Int J Tour Res 12(5):550–560

Blake A, Sinclair MT, Soria JAC (2006) Tourism productivity: evidence from the United Kingdom. Ann Tourism Res 33(4):1099–1120

Brida JG, Pulina M (2010) A literature review on the tourism-led-growth hypothesis. Working paper CRENoS201017. Centre for North South Economic Research, Sardinia

Brida JG, Cortes-Jimenez I, Pulina M (2016) Has the tourism-led growth hypothesis been validated? A literature review. Curr Issues Tourism 19(5):394–430

Chatziantoniou I, Filis G, Eeckels B, Apostolakis A (2013) Oil prices, tourism income and economic growth: a structural VAR approach for European Mediterranean countries. Tourism Manag 36:331–341

Chen M-H (2010) The economy, tourism growth and corporate performance in the Taiwanese hotel industry. Tourism Manag 31:665–675

Croes R (2006) A paradigm shift to a new strategy for small island economies: embracing demand side economics for value enhancement and long term economic stability. Tourism Manag 27:453–465

Dhungel KR (2015) An econometric analysis on the relationship between tourism and economic growth: empirical evidence from Nepal. Int J Econ Financ Manag 3(2):84–90

Dumitrescu EI, Hurlin C (2012) Testing for Granger non-causality in heterogeneous panels. Econ Modell 29(4):1450–1460

Daniel Mminele (2016) The role of BRICS in the global economy. Speech at the Bundesbank Regional Office in North Rhine-Westphalia, Düsseldorf, Germany. https://www.bis.org/review/r160720c.pdf

Goldsmith RW (1969) Financial structure and development (No. HG174 G57)

Hassan MK, Sanchez B, Yu JS (2011) Financial development and economic growth: new evidence from panel data. Quart Rev Econ Financ 51(1):88–104

Haug AA (2002) Temporal aggregation and the power of cointegration tests: A Monte Carlo study. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 64:399–412

Henry EW, Deane B (1997) The contribution of tourism to the economy of Ireland in 1990 and 1995. Tourism Manag 18(8):535–553

Hur J, Raj M, Riyanto YE (2006) Finance and trade: a cross-country empirical analysis on the impact of financial development and asset tangibility on international trade. World Dev 34(10):1728–1741

Im KS, Pesaran MH, Shin Y (2003) Testing for unit roots in heterogeneous panels. J Econ 115(1):53–74

Kadir N, Karim MZA (2012) Tourism and economic growth in Malaysia: evidence from tourist arrivals from Asean-S countries. Econ Res Ekonomska istraživanja 25(4):1089–1100

Katircioglu S (2009) Testing the tourism-led growth hypothesis: the case of Malta. Acta Oeconomica 59(3):331–343

Khan M, Senhadji A (2003) Financial development and economic growth: a review and new evidence. J Afr Econ 12:89–110

Khoshnevis Yazdi S, Homa Salehi K, Soheilzad M (2017) The relationship between tourism, foreign direct investment and economic growth: evidence from Iran. Curr Issues Tourism 20(1):15–26

Kim HJ, Chen MH (2006) Tourism expansion and economic development: the case of Taiwan. Tourism Manag 27(5):925–933

King R, Levine R (1993) Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth: theory and evidence. J Monet Econ 32:513–542

Kreishan FM (2010) Tourism and economic growth: the case of Jordan. Eur J Soc Sci 15:229–234

Krueger A (1980) Trade policy as an input to development. Am Econ Rev 70:188–292

Kumar RR (2014) Exploring the role of technology, tourism and financial development: an empirical study of Vietnam. Qual Quant 48(5):2881–2898

Levine R (1997) Financial development and economic growth: views and agenda. J Econ Lit 35(2):688–726

Lee CC, Chang CP (2008) Tourism development and economic growth: a closer look at panels. Tourism Manag 29(1):180–192

Levin A, Lin CF, Chu CSJ (2002) Unit root tests in panel data: asymptotic and finite-sample properties. J Econ 108(1):1–24

Mallick L, Mallesh U, Behera J (2016) Does tourism affect economic growth in Indian states? Evidence from panel ARDL model. Theor Appl Econ 23(1):183–194

Mastny L (2001) Treading lightly: new paths for international tourism. In: Peterson JA (ed) World Watch Paper 159. World Watch Institute

McKinnon RI (1964) Foreign exchange constraints in economic development and efficient aid allocation. Econ J 74(294):388–409

McKinnon RI (1973) Money and capital in economic development. The Brookings Institution, Washington

Narayan PK (2004) Economic impact of tourism on Fiji’s economy: empirical evidence from the computable general equilibrium model. Tourism Econ 10(4):419–433

Oh CO (2005) The contribution of tourism development to economic growth in the Korean economy. Tourism Manag 26(1):39–44

Ohlan R (2015) The impact of population density, energy consumption, economic growth and trade openness on CO 2 emissions in India. Nat Hazards 79(2):1409–1428

Ohlan R (2017) The relationship between tourism, financial development and economic growth in India. Future Bus J 3(1):9–22

Parrilla JC, Font AR, Nadal JR (2007) Tourism and long-term growth a Spanish perspective. Ann Tourism Res 34(3):709–726

Payne JE, Mervar A (2010) Research note: the tourism-growth nexus in Croatia. Tourism Econ 16(4):1089–1094

Pesaran MH, Shin Y, Smith RJ (2001) Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. J Appl Econ 16(3):289–326

Po WC, Huang BN (2008) Tourism development and economic growth—a nonlinear approach. Phys A Stat Mech Appl 387(22):5535–5542

Pradhan RP, Dasgupta P, Bele S (2013) Finance, development and economic growth in BRICS: a panel data analysis. J Quant Econ 11(1–2):308–322

Ridderstaat J, Oduber M, Croes R, Nijkamp P, Martens P (2014) Impacts of seasonal patterns of climate on recurrent fluctuations in tourism demand: evidence from Aruba. Tourism Manag 41:245–256

Schumpeter JA (1911) The theory of economic development: an inquiry into profits, capital, credit, interest, and the business cycle. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, p 1934

Shaw ES (1973) Financial deepening in economic development. Oxford University Press, London

Sugiyarto G, Blake A, Sinclair MT (2003) Tourism and globalization: economic impact in Indonesia. Ann Tourism Res 30(3):683–701

Szivas E, Riley M (1999) Tourism employment during economic transition. Ann Tourism Res 26(4):747–771

Savaş B, Beşkaya A, Şamiloğlu F (2010) Analyzing the impact of international tourism on economic growth in Turkey. Uluslararası Yönetim İktisat ve İşletme Dergisi 6(12):121–136

Schubert SF, Brida JG, Risso WA (2011) The impacts of international tourism demand on economic growth of small economies dependent on tourism. Tourism Manag 32(2):377–385

Song H, Lin S (2010) Impacts of the financial and economic crisis on tourism in Asia. J Travel Res 49(1):16–30

Tang CF (2013) Temporal Granger causality and the dynamics relationship between real tourism receipts, real income and real exchange rates in Malaysia. Int J Tourism Res 15(3):272–284

Tang CF, Tiwari AK, Shahbaz M (2016) Dynamic inter-relationships among tourism, economic growth and energy consumption in India. Geosyst Eng 19(4):158–169

United Nations World Tourism Report (2014) Annual report 2014

World Travel & Tourism Council (2012) Travel & Tourism Economic Impact. World, London: World Travel & Tourism Council.

World Travel and Tourism Council (2016) Global travel and tourism economic impact update August 2016

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

This research has received no specific funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Haroon Rasool & Md. Tarique

Department of Commerce, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India

Shafat Maqbool

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

HR has written introduction, research methodology and results and discussion part. Review of literature and data analysis was done by SM. Conclusion was written jointly by HR and SM. MT has provided useful inputs and finalized the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Haroon Rasool .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Authors declare that there are no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rasool, H., Maqbool, S. & Tarique, M. The relationship between tourism and economic growth among BRICS countries: a panel cointegration analysis. Futur Bus J 7 , 1 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Download citation

Received : 02 August 2019

Accepted : 30 November 2020

Published : 05 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s43093-020-00048-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Economic growth

- Inbound tourism

- Financial development

- Cointegration

- Panel granger causality

JEL Classification

- Press Releases

- Press Enquiries

- Travel Hub / Blog

- Brand Resources

- Newsletter Sign Up

- Global Summit

- Hosting a Summit

- Upcoming Events

- Previous Events

- Event Photography

- Event Enquiries

- Our Members

- Our Associates Community

- Membership Benefits

- Enquire About Membership

- Sponsors & Partners

- Insights & Publications

- WTTC Research Hub

- Economic Impact

- Knowledge Partners

- Data Enquiries

- Hotel Sustainability Basics

- Community Conscious Travel

- SafeTravels Stamp Application

- SafeTravels: Global Protocols & Stamp

- Security & Travel Facilitation

- Sustainable Growth

- Women Empowerment

- Destination Spotlight - SLO CAL

- Vision For Nature Positive Travel and Tourism

- Governments

- Consumer Travel Blog

- ONEin330Million Campaign

- Reunite Campaign

Economic Impact Research

- In 2023, the Travel & Tourism sector contributed 9.1% to the global GDP; an increase of 23.2% from 2022 and only 4.1% below the 2019 level.

- In 2023, there were 27 million new jobs, representing a 9.1% increase compared to 2022, and only 1.4% below the 2019 level.

- Domestic visitor spending rose by 18.1% in 2023, surpassing the 2019 level.

- International visitor spending registered a 33.1% jump in 2023 but remained 14.4% below the 2019 total.

Click here for links to the different economy/country and regional reports

Why conduct research?

From the outset, our Members realised that hard economic facts were needed to help governments and policymakers truly understand the potential of Travel & Tourism. Measuring the size and growth of Travel & Tourism and its contribution to society, therefore, plays a vital part in underpinning WTTC’s work.

What research does WTTC carry out?

Each year, WTTC and Oxford Economics produce reports covering the economic contribution of our sector in 185 countries, for 26 economic and geographic regions, and for more than 70 cities. We also benchmark Travel & Tourism against other economic sectors and analyse the impact of government policies affecting the sector such as jobs and visa facilitation.

Visit our Research Hub via the button below to find all our Economic Impact Reports, as well as other reports on Travel and Tourism.

- Topics ›

- Impact of inflation on travel and tourism worldwide ›

Travel and tourism is one of the fastest growing sectors

Sponsored post by booking.com.

For nine consecutive years before the COVID-19 pandemic, the growth of the global travel and tourism sector exceeded that of the global economy. As the damage to the tourism sector caused by the pandemic slowly subsides, the sector is forecast to pick up the pace again and grow by 5.8% annually over the 2022 to 2032 period, more than twice as fast as the forecast global GDP . The sector is thus one of the main powerhouses of global economic growth.

When compared with other sectors, travel and tourism also ranks among the fastest growing. With a GDP growth rate of 3.5% in 2019, travel and tourism trailed only behind information and communication and financial services. Apart from technology and capital, our society is also heavily driven by the movement of people, which contributes to globalization and the growing connectedness of the world.

Description

This infographic shows the total global GDP growth of selected industries in 2019.

Can I integrate infographics into my blog or website?

Yes, Statista allows the easy integration of many infographics on other websites. Simply copy the HTML code that is shown for the relevant statistic in order to integrate it. Our standard is 660 pixels, but you can customize how the statistic is displayed to suit your site by setting the width and the display size. Please note that the code must be integrated into the HTML code (not only the text) for WordPress pages and other CMS sites.

Infographic Newsletter

Statista offers daily infographics about trending topics, covering: Economy & Finance , Politics & Society , Tech & Media , Health & Environment , Consumer , Sports and many more.

Related Infographics

Interest rates, latest economic data throws cold water on rate cut hopes, sponsored post by booking.com, 5% of americans are digital nomads, military spending, military spending rises fastest in asia, eastern europe, global economic outlook, imf: g7 faster to reach coveted 'soft landing', offline hotel bookings defy digitalization, the evolution of air travel, haiti and the dominican republic: contrasting fortunes, social media shapes travel experiences, top 10 nature destinations in southeast asia, the how of improving social cohesion with local tourism, european hospitality sector experiences unprecedented levels of bankruptcies, top 10 history and culture destinations in southeast asia.

- Who may use the "Chart of the Day"? The Statista "Chart of the Day", made available under the Creative Commons License CC BY-ND 3.0, may be used and displayed without charge by all commercial and non-commercial websites. Use is, however, only permitted with proper attribution to Statista. When publishing one of these graphics, please include a backlink to the respective infographic URL. More Information

- Which topics are covered by the "Chart of the Day"? The Statista "Chart of the Day" currently focuses on two sectors: "Media and Technology", updated daily and featuring the latest statistics from the media, internet, telecommunications and consumer electronics industries; and "Economy and Society", which current data from the United States and around the world relating to economic and political issues as well as sports and entertainment.

- Does Statista also create infographics in a customized design? For individual content and infographics in your Corporate Design, please visit our agency website www.statista.design

Any more questions?

Get in touch with us quickly and easily. we are happy to help.

Feel free to contact us anytime using our contact form or visit our FAQ page .

Statista Content & Design

Need infographics, animated videos, presentations, data research or social media charts?

More Information

The Statista Infographic Newsletter

Receive a new up-to-date issue every day for free.

- Our infographics team prepares current information in a clear and understandable format

- Relevant facts covering media, economy, e-commerce, and FMCG topics

- Use our newsletter overview to manage the topics that you have subscribed to

- Understanding Poverty

- Competitiveness

Tourism and Competitiveness

- Publications

The tourism sector provides opportunities for developing countries to create productive and inclusive jobs, grow innovative firms, finance the conservation of natural and cultural assets, and increase economic empowerment, especially for women, who comprise the majority of the tourism sector’s workforce. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, tourism was the world’s largest service sector—providing one in ten jobs worldwide, almost seven percent of all international trade and 25 percent of the world’s service exports —a critical foreign exchange generator. In 2019 the sector was valued at more than US$9 trillion and accounted for 10.4 percent of global GDP.

Tourism offers opportunities for economic diversification and market-creation. When effectively managed, its deep local value chains can expand demand for existing and new products and services that directly and positively impact the poor and rural/isolated communities. The sector can also be a force for biodiversity conservation, heritage protection, and climate-friendly livelihoods, making up a key pillar of the blue/green economy. This potential is also associated with social and environmental risks, which need to be managed and mitigated to maximize the sector’s net-positive benefits.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been devastating for tourism service providers, with a loss of 20 percent of all tourism jobs (62 million), and US$1.3 trillion in export revenue, leading to a reduction of 50 percent of its contribution to GDP in 2020 alone. The collapse of demand has severely impacted the livelihoods of tourism-dependent communities, small businesses and women-run enterprises. It has also reduced government tax revenues and constrained the availability of resources for destination management and site conservation.

Naturalist local guide with group of tourist in Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve Ecuador. Photo: Ammit Jack/Shutterstock

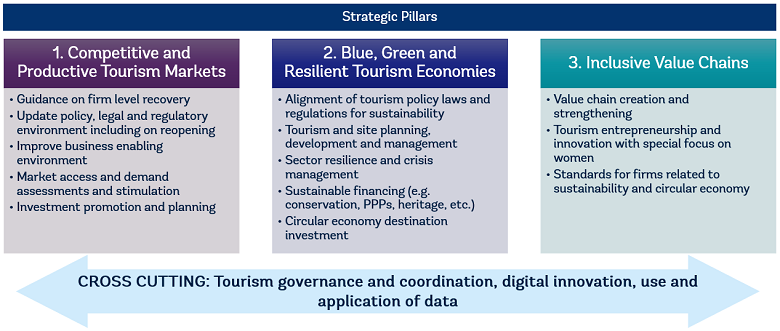

Tourism and Competitiveness Strategic Pillars

Our solutions are integrated across the following areas:

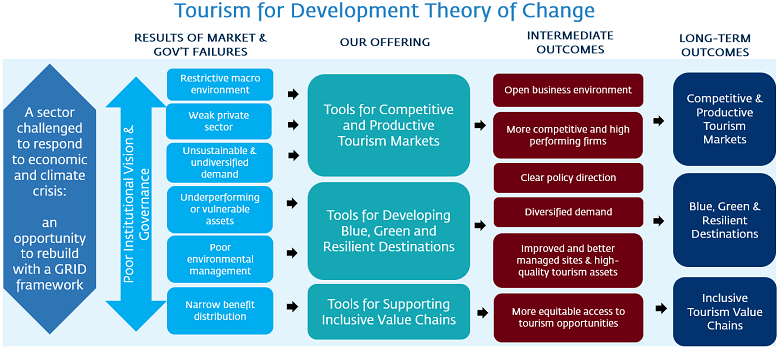

- Competitive and Productive Tourism Markets. We work with government and private sector stakeholders to foster competitive tourism markets that create productive jobs, improve visitor expenditure and impact, and are supportive of high-growth, innovative firms. To do so we offer guidance on firm and destination level recovery, policy and regulatory reforms, demand diversification, investment promotion and market access.

- Blue, Green and Resilient Tourism Economies. We support economic diversification to sustain natural capital and tourism assets, prepare for external and climate-related shocks, and be sustainably managed through strong policy, coordination, and governance improvements. To do so we offer support to align the tourism enabling and policy environment towards sustainability, while improving tourism destination and site planning, development, and management. We work with governments to enhance the sector’s resilience and to foster the development of innovative sustainable financing instruments.

- Inclusive Value Chains. We work with client governments and intermediaries to support Small and Medium sized Enterprises (SMEs), and strengthen value chains that provide equitable livelihoods for communities, women, youth, minorities, and local businesses.

The successful design and implementation of reforms in the tourism space requires the combined effort of diverse line ministries and agencies, and an understanding of the impact of digital technologies in the industry. Accordingly, our teams support cross-cutting issues of tourism governance and coordination, digital innovation and the use and application of data throughout the three focus areas of work.

Tourism and Competitiveness Theory of Change

Examples of our projects:

- In Indonesia , a US$955m loan is supporting the Government’s Integrated Infrastructure Development for National Tourism Strategic Areas Project. This project is designed to improve the quality of, and access to, tourism-relevant basic infrastructure and services, strengthen local economy linkages to tourism, and attract private investment in selected tourism destinations. In its initial phases, the project has supported detailed market and demand analyses needed to justify significant public investment, mobilized integrated tourism destination masterplans for each new destination and established essential coordination mechanisms at the national level and at all seventeen of the Project’s participating districts and cities.

- In Madagascar , a series of projects totaling US$450m in lending and IFC Technical Assistance have contributed to the sustainable growth of the tourism sector by enhancing access to enabling infrastructure and services in target regions. Activities under the project focused on providing support to SMEs, capacity building to institutions, and promoting investment and enabling environment reforms. They resulted in the creation of more than 10,000 jobs and the registration of more than 30,000 businesses. As a result of COVID-19, the project provided emergency support both to government institutions (i.e., Ministry of Tourism) and other organizations such as the National Tourism Promotion Board to plan, strategize and implement initiatives to address effects of the pandemic and support the sector’s gradual relaunch, as well as to directly support tourism companies and workers groups most affected by the crisis.

- In Sierra Leone , an Economic Diversification Project has a strong focus on sustainable tourism development. The project is contributing significantly to the COVID-19 recovery, with its focus on the creation of six new tourism destinations, attracting new private investment, and building the capacity of government ministries to successfully manage and market their tourism assets. This project aims to contribute to the development of more circular economy tourism business models, and support the growth of women- run tourism businesses.

- Through the Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness: Tourism Response, Recovery and Resilience to the COVID-19 Crisis initiative and the Tourism for Development Learning Series , we held webinars, published insights and guidance notes as well as formed new partnerships with Organization of Eastern Caribbean States, United Nations Environment Program, United Nations World Tourism Organization, and World Travel and Tourism Council to exchange knowledge on managing tourism throughout the pandemic, planning for recovery and building back better. The initiative’s key Policy Note has been downloaded more than 20,000 times and has been used to inform recovery initiatives in over 30 countries across 6 regions.

- The Global Aviation Dashboard is a platform that visualizes real-time changes in global flight movements, allowing users to generate 2D & 3D visualizations, charts, graphs, and tables; and ranking animations for: flight volume, seat volume, and available seat kilometers. Data is available for domestic, intra-regional, and inter-regional routes across all regions, countries, airports, and airlines on a daily, weekly, or monthly basis from January 2020 until today. The dashboard has been used to track the status and recovery of global travel and inform policy and operational actions.

Traditional Samburu women in Kenya. Photo: hecke61/Shutterstock.

Featured Data

We-Fi WeTour Women in Tourism Enterprise Surveys (2019)

- Sierra Leone | Ghana

Featured Reports

- Destination Management Handbook: A Guide to the Planning and Implementation of Destination Management (2023)

- Blue Tourism in Islands and Small Tourism-Dependent Coastal States : Tools and Recovery Strategies (2022)

- Resilient Tourism: Competitiveness in the Face of Disasters (2020)

- Tourism and the Sharing Economy: Policy and Potential of Sustainable Peer-to-Peer Accommodation (2018)

- Supporting Sustainable Livelihoods through Wildlife Tourism (2018)

- The Voice of Travelers: Leveraging User-Generated Content for Tourism Development (2018)

- Women and Tourism: Designing for Inclusion (2017)

- Twenty Reasons Sustainable Tourism Counts for Development (2017)

- An introduction to tourism concessioning:14 characteristics of successful programs. The World Bank, 2016)

- Getting financed: 9 tips for community joint ventures in tourism . World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and World Bank, (2015)

- Global investment promotion best practices: Winning tourism investment” Investment Climate (2013)

Country-Specific

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia: Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- Demand Analysis for Tourism in African Local Communities (2018)

- Tourism in Africa: Harnessing Tourism for Growth and Improved Livelihoods . Africa Development Forum (2014)

COVID-19 Response

- Expecting the Unexpected : Tools and Policy Considerations to Support the Recovery and Resilience of the Tourism Sector (2022)

- Rebuilding Tourism Competitiveness. Tourism response, recovery and resilience to the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- COVID-19 and Tourism in South Asia Opportunities for Sustainable Regional Outcomes (2020)

- WBG support for tourism clients and destinations during the COVID-19 crisis (2020)

- Tourism for Development: Tourism Diagnostic Toolkit (2019)

- Tourism Theory of Change (2018)

Country -Specific

- COVID Impact Mitigation Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Preparedness for Reopening Survey Results (South Africa) (2020)

- COVID Study (Fiji) (2020) with IFC

Featured Blogs

- Fiona Stewart, Samantha Power & Shaun Mann , Harnessing the power of capital markets to conserve and restore global biodiversity through “Natural Asset Companies” | October 12 th 2021

- Mari Elka Pangestu , Tourism in the post-COVID world: Three steps to build better forward | April 30 th 2021

- Hartwig Schafer , Regional collaboration can help South Asian nations rebuild and strengthen tourism industry | July 23 rd 2020

- Caroline Freund , We can’t travel, but we can take measures to preserve jobs in the tourism industry | March 20 th 2020

Featured Webinars

- Destination Management for Resilient Growth . This webinar looks at emerging destinations at the local level to examine the opportunities, examples, and best tools available. Destination Management Handbook

- Launch of the Future of Pacific Tourism. This webinar goes through the results of the new Future of Pacific Tourism report. It was launched by FCI Regional and Global Managers with Discussants from the Asian Development Bank and Intrepid Group.

- Circular Economy and Tourism . This webinar discusses how new and circular business models are needed to change the way tourism operates and enable businesses and destinations to be sustainable.

- Closing the Gap: Gender in Projects and Analytics . The purpose of this webinar is to raise awareness on integrating gender considerations into projects and provide guidelines for future project design in various sectoral areas.

- WTO Tourism Resilience: Building forward Better. High-level panelists from Sri Lanka, Costa Rica, Jordan and Kenya discuss how donors, governments and the private sector can work together most effectively to rebuild the tourism industry and improve its resilience for the future.

- Tourism Watch

- [email protected]

Launch of Blue Tourism Resource Portal

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 24 February 2024

Modeling the link between tourism and economic development: evidence from homogeneous panels of countries

- Pablo Juan Cárdenas-García ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1779-392X 1 ,

- Juan Gabriel Brida 2 &

- Verónica Segarra 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 308 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1533 Accesses

Metrics details

- Development studies

Having previously analyzed the relationship between tourism and economic growth from distinct perspectives, this paper attempts to fill the void existing in scientific research on the relationship between tourism and economic development, by analyzing the relationship between these variables using a sample of 123 countries between 1995 and 2019. The Dumistrescu and Hurlin adaptation of the Granger causality test was used. This study takes a critical look at causal analysis with heterogeneous panels, given the substantial differences found between the results of the causal analysis with the complete panel as compared to the analysis of homogeneous country groups, in terms of their dynamics of tourism specialization and economic development. On the one hand, a one-way causal relationship exists from tourism to development in countries having low levels of tourism specialization and development. On the other hand, a one-way causal relationship exists by which development contributes to tourism in countries with high levels of development and tourism specialization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

The economic commitment of climate change

Frequent disturbances enhanced the resilience of past human populations

Introduction.

Across the world, tourism is one of the most important sectors. It has undergone exponential growth since the mid-1900s and is currently experiencing growth rates that exceed those of other economic sectors (Yazdi, 2019 ).

Today, tourism is a major source of income for countries that specialize in this sector, generating 5.8% of the global GDP (5.8 billion US$) in 2021 (UNWTO, 2022 ) and providing 5.4% of all jobs (289 million) worldwide. Although its relevance is clear, tourism data have declined dramatically due to the recent impact of the Covid-19 health crisis. In 2019, prior to the pandemic (UNWTO, 2020 ), tourism represented 10.3% of the worldwide GDP (9.6 billion US$), with the number of tourism-related jobs reaching 10.2% of the global total (333 million). With the evolution of the pandemic and the regained trust of tourists across the globe, it is estimated that by 2022, approximately 80% of the pre-pandemic figures will be attained, with a full recovery being expected by 2024 (UNWTO, 2022 ).

Given the importance of this economic activity, many countries consider tourism to be a tool enabling economic growth (Corbet et al., 2019 ; Ohlan, 2017 ; Xia et al., 2021 ). Numerous works have analyzed the relationship between increased tourism and economic growth; and some systematic reviews have been carried out on this relationship (Brida et al., 2016 ; Ahmad et al., 2020 ), examining the main contributions over the first two decades of this century. These reviews have revealed evidence in this area: in some cases, it has been found that tourism contributes to economic growth while, in other cases, the economic cycle influences tourism expansion. Moreover, other works offer evidence of a bi-directional relationship between these variables.

Distinct international organizations (OECD, 2010 ; UNCTAD, 2011 ) have suggested that not only does tourism promote economic growth, it also contributes to socio-economic advances in the host regions. This may be the real importance of tourism, since the ultimate objective of any government is to improve a country’s socio-economic development (UNDP, 1990 ).

The development of economic and other policies related to the economic scope of tourism, in addition to promoting economic growth, are also intended to improve other non-economic factors such as education, safety, and health. Improvements in these factors lead to a better life for the host population (Lee, 2017 ; Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

Given tourism’s capacity as an instrument of economic development (Cárdenas-García et al., 2015 ), distinct institutions such as the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, the United Nations World Tourism Organization and the World Bank, have begun funding projects that consider tourism to be a tool for improved socio-economic development, especially in less advanced countries (Carrillo and Pulido, 2019 ).

This new trend within the scientific literature establishes, firstly, that tourism drives economic growth and, secondly, that thanks to this economic growth, the population’s economic conditions may be improved (Croes et al., 2021 ; Kubickova et al., 2017 ). However, to take advantage of the economic growth generated by tourism activity to boost economic development, specific policies should be developed. These policies should determine the initial conditions to be met by host countries committed to tourism as an instrument of economic development. These conditions include regulation, tax system, and infrastructure provision (Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Lejárraga and Walkenhorst, 2013 ; Meyer and Meyer, 2016 ).

Therefore, it is necessary to differentiate between the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, whereby tourism boosts the economy of countries committed to tourism, traditionally measured through an increase in the Gross Domestic Product (Alcalá-Ordóñez et al., 2023 ; Brida et al., 2016 ), and the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic development, which measures the effect of tourism on other factors (not only economic content but also inequality, education, and health) which, together with economic criteria, serve as the foundation to measure a population’s development (Todaro and Smith, 2020 ).

However, unlike the analysis of the relationship between tourism and economic growth, few empirical studies have examined tourism’s capacity as a tool for development (Bojanic and Lo, 2016 ; Cárdenas-García and Pulido-Fernández, 2019 ; Croes, 2012 ).

To help fill this gap in the literature analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, this work examines the contribution of tourism to economic development, given that the relationship between tourism and economic growth has been widely analyzed by the scientific literature. Moreover, given that the literature has demonstrated that tourism contributes to economic growth, this work aims to analyze whether it also contributes to economic development, considering development in the broadest possible sense by including economic and socioeconomic variables in the multi-dimensional concept (Wahyuningsih et al., 2020 ).

Therefore, based on the results of this work, it is possible to determine whether the commitment made by many international organizations and institutions in financing tourism projects designed to improve the host population’s socioeconomic conditions, especially in countries with lower development levels, has, in fact, resulted in improved development levels.

It also presents a critical view of causal analyses that rely on heterogeneous panels, examining whether the conclusions reached for a complete panel differ from those obtained when analyzing homogeneous groups within the panel. As seen in the literature review analyzing the relationship between tourism and economic development, empirical works using panel data from several countries tend to generalize the results obtained to the entire panel, without verifying whether, in fact, they are relevant for all of the analyzed countries or only some of the same. Therefore, this study takes an innovative approach by examining the panel countries separately, analyzing the homogeneous groups distinctly.