National Geographic

Le miraculé du 11 Septembre

Au 22ème étage d'une des deux tours jumelles, Pasquale Buzzelli a survécu à une veritable tempête de débris. Evitant un nombre invraisemblable d'obstacles guidé par son instinct de survie, ce miraculé nous raconte en détail son expérience. Cette histoire inédite donne un nouveau souffle à l'un des jours les plus sombres des Etats-Unis...

The Miracle Survivors

Just three months after the World Trade Center collapsed on top of him, Pasquale Buzzelli, a brawny 34-year-old structural engineer, returned to his desk at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Buzzelli, a numbers person used to calculating risk, still hadn’t been able to comprehend what happened to him. “When you start to think about the numbers,” he says, “it doesn’t really seem possible that I’m alive.” Still, he told himself, “Shrug it off, move on, get back in the saddle.”

Buzzelli’s office had been on the 64th floor of the North Tower. At about 10 a.m. on September 11, 2001, he’d phoned his wife for the second time that morning. “Don’t worry,” he said. She was seven months pregnant and at their home in Rivervale, New Jersey. She’d been watching on the giant TV in their family room—she’d turned it on after his first phone call. He assured her that he and a dozen other employees were about to head down Stairwell B. He’d investigated. It was free of smoke. Buzzelli took the lead, his briefcase over his shoulder. It was slow going. The stairs were narrow, and clogged with people.

Then, as he reached the 22nd floor, the building shook, stairs started to heave. It sounded to Buzzelli like heavy objects were being dropped right above his head. The sound got louder, closer. He dove into a corner. “I felt the walls next to me crack and buckle on top of me,” he says. Suddenly, he seemed to be in free fall, and the walls seemed to separate and move away from him.

Maybe two hours later, he regained consciousness on a slab of concrete 180 feet below the 22nd floor. (He may be the source of the rumor that someone surfed the collapse and lived.) He was atop a hill of rubble in the midst of an endless field of rubble, smoke, and fire, sitting as if in an armchair, his feet dangling over the edge. His bag was gone. He felt numb. The air was thick with smoke and dust. He heard explosions.

Buzzelli, who is six two, 270 pounds (just that morning, he’d decided to join Weight Watchers), looked around and thought, I’m dead . His right leg, though, was in pain, a sign, he understood, that he was alive. He pulled his shirt over his face to breathe. He shouted for help. A little later, a fireman appeared a short distance below.

“Holy shit, guys, we have a civilian up there,” the fireman called. For a few minutes, a raging fire drove rescuers away. Buzzelli looked around for something sharp. He didn’t want to die by burning alive. Soon, though, half a dozen firefighters reached Buzzelli and led him across the debris field, a rope around his waist. He slid down mangled beams, then, when he could no longer climb, the firemen passed him along on a stretcher, talking to keep him conscious. One fireman said, “Man, you are a heavy fuck. What’s your name?”

By December 2001, though still on crutches—he’d suffered a fractured foot—Buzzelli thought he should get back to his job. He’d grown up in Jersey City, son of Italian immigrants, had won a scholarship to Cooper Union, and had immediately been hired by the Port Authority.

He didn’t believe in therapy. It seemed like babying himself. “You feel stupid even talking about September 11,” he says. “How are the people who lost a loved one supposed to feel? If I were them, I’d say, ‘What the hell are you talking about? You’re alive. What bad days do you have?’ ” Buzzelli loved his job; the Port Authority had always been like a big family for him. Port Authority had lost 84 employees. People were happy to see a survivor.

Buzzelli, though, had trouble fitting in. “I couldn’t understand certain things,” he says. “Things I would have brushed off or discussed rationally before. I would just lose it. One time, I punched the wall.” Buzzelli had little practice at being emotional. “Before, I hardly ever cried,” he says, “and that’s one of the problems now. Talking about the people with me that died, I get choked up, I can’t control it at all.”

At work, there were constant reminders of those people. He developed an ulcer. He’d have nightmares, not about the collapse but about being trapped in an elevator—again and again. “There was something definitely wrong with me,” he says. After a short time, Buzzelli had to take a leave. For the next seven months, he mostly sat in a chair in front of the TV or by the pool, trying to get his head together.

“People think it ended when my husband walked through the door alive,” says Buzzelli’s wife, Louise. “That’s when it began for us. You can’t understand why you feel so bad when you should feel so elated. You can’t make sense of anything.”

To an extent, we are all survivors. One study asserted that 17 percent of the entire United States population outside New York reported symptoms like nightmares, sleeplessness, and anxiety in the days after September 11. Still, the more intense the exposure, the greater its effect. So for every non–New Yorker who suffered, almost three New Yorkers reported symptoms. And the closer that New Yorker was to the Trade Center, the more he felt it. You could measure the difference in blocks. People below Canal Street reported symptoms at almost three times the rate of those below 110th Street. If this is true, then the most intense experience of survival was had by sixteen who experienced almost incomprehensible luck that day. These people—a bookkeeper, an office temp, an engineer, a Port Authority cop, and twelve firemen—survived despite having the World Trade Center collapse on top of them.

For them, surviving has proved to be a complicated task. As one survivor’s wife explains, “Everyone else feels like 9/11 was a long time ago. I still feel like we are stuck on September 12, not really able to move beyond it.” And, as she inevitably reminds herself, they are the lucky ones.

S ixteen people survived inside the collapse of the World Trade Center, and they were all in Stairwell B of the North Tower, in the center of the building. The survivors were spread out between floors 22 and 1. A step or two slower meant death, but so, too, did a step or two faster. Captain Jay Jonas and five of his firefighters from Ladder Six, based in Chinatown, had been on the 27th floor of the North Tower when they heard a rumble, felt the staircase sway, watched as the lights flickered off and on. A captain from another company let Jonas know the cause of the disturbance: The South Tower had just collapsed.

“I’m pulling the plug,” Jonas said, and gave the order to evacuate. He didn’t tell his men why; they didn’t know that the South Tower was gone. “For me, that was the scariest point,” said Jonas. “I’m thinking, We’re not going to make it out. ”

Each firefighter carried close to 100 pounds of equipment that day, but Jonas, a stickler for regulations, wasn’t about to let them drop any of it. Still, they moved down the stairs at a good pace. Matty Komorowski was last in line, and not worried. “We had a building around us. Everything was fine. It was clear as a bell.”

On about the twentieth floor, they ran into Josephine Harris, a heavyset, 59-year-old bookkeeper who’d worked at the Port Authority for six months. Harris had a limp, but she bulled ahead. She was stubborn that way. Just a few months before, she’d been hit by a car. “My back went up in the air,” she says. “I came down on my side.” Still, she’d signed herself out of the hospital that same day. “I put a brace on my leg and went on about my business,” she says, matter-of-factly reassuring herself, “It’s not my time yet.” On September 11, with one good leg, she’d already made it down 50 floors.

Catching sight of the limping Harris, firefighter Billy Butler looked at another firefighter, who looked at Jonas. “What do you want to do with her, Cap?”

Jonas lives in Goshen, New York, just over an hour from his firehouse, and tends to take emergencies in stride—he delivered two of his three kids in the backseat of his car. That day, Jonas was, at 43, the oldest of his firemen. Among them, they had more than half a dozen young children. Others had already run down the narrow stairway by Harris. Would anyone have blamed Jonas if he had left her to struggle on alone, if he had chosen six lives over one?

“That’s not in the culture of the Fire Department,” Jonas would say. “If somebody needs help, we got to give it a shot. It wasn’t a difficult decision.”

“We got to bring her with us,” he told his company. By that point, Harris could barely stand. Butler, short, barrel-chested, the company’s strongest man, put her arm over his shoulder. The company’s pace slowed to Harris’s.

Then, on the fifth floor, Harris stopped. She wasn’t thinking of dying, she’d later say. She was simply exhausted.

Jonas hustled off to look for a chair (he couldn’t find one). They’d carry her down. That’s when Port Authority officer David Lim ran into Jonas. Lim, a canine officer, had locked his yellow Lab in the South Tower, promising to return, and run to the North Tower to help. Now he was racing down the stairs.

A Port Authority captain yelled at Lim to get moving, but he said, “You go ahead,” and he, too, put an arm around Harris, helping to carry her to the fourth floor.

That was when the wind started, even before the noise. “No one realizes about the wind,” says Komorowski.

The building was pancaking down from the top and, in the process, blasting air down the stairwell. The wind lifted Komorowski off his feet. “I was taking a staircase at a time,” he says, “It was a combination of me running and getting blown down.” Lim says Komorowski flew over him. Eight seconds later—that’s how long it took the building to come down—Komorowski landed three floors lower, in standing position, buried to his knees in pulverized Sheetrock and cement.

Lim landed near Harris. “If Josephine doesn’t slow me down, I’m dead,” he’d later say. “I figured this out.” That captain who’d urged Lim to go ahead didn’t make it. “Josephine Harris saved my life,” he says definitively. Harris landed on her side, clinging to the boot of Billy Butler.

A firehouse is a physically intimate place. Twenty-five guys take turns cooking together, bunking together, living together for days at a time. They call one another brother, enjoy a near-tribal camaraderie, much of it around the firehouse’s kitchen table, where a posted sign reads, WHAT YOU HEAR HERE STAYS HERE.

Komorowski was recently promoted to lieutenant, and the first floor of his new station in an Orthodox Jewish section of Brooklyn contains barbells, a pool table, a gas pump, a garbage can of dog food, a soda machine, a tool bench, a pole, and two big red trucks. Off to one side is a memorial to the 343 firefighters lost in the World Trade Center. A minute after Komorowski, now 40, steps into the communications room, an alarm sounds. “Can you wait?” Komorowski says, though it’s not really a question. He pulls his gear over his pants. As a truck leaves, a fireman shouts, “Can you close the door?”

The firehouse hasn’t been a place where people generally “give themselves permission to share their emotions.” The environment has not been therapy-friendly. Maybe that’s good. “This is a job for physical, proactive, problem-solving people, which are great qualities if my house is on fire,” says Malachy Corrigan, director of the department’s counseling unit. Emotional distance is probably protective. Sooner or later, every fireman hauls a burnt child out of a fire. “You have to tell yourself that this dead kid I’m pulling out of a fire is no different than pulling a deer out of the woods,” explains Butler. “You can’t look at it like, Oh, my God, I’m pulling out my own child. You can’t go killing yourself.”

September 11 overran the usual defenses. Jonas and his men, finally freed from their stairwell, looked around at fires and flattened buildings. They thought they were witnessing a nuclear attack. “We usually show up at a chaotic situation, we make it better and we go home, almost every time,” says Jonas. “In the World Trade Center that really didn’t happen.” Well-disciplined emotions were suddenly impossible to contain.

Probably half the city’s firefighters have gone into therapy—6,100 uniformed people have received counseling through the department. The department now has 60 full-time counselors instead of the 9 it employed before September 11.

Jonas waited to make his therapy appointment, then nearly backed out. He’d had a tough winter, 2003, worse than the last, which confused him. He thought he should be doing better by now. “I was having nightmares fairly consistently where I’d wake up screaming,” he explains at his home in Orange County one afternoon. Jonas is six feet, 245 pounds, with a gentle voice and an intense way of tipping his head down while gazing up at a listener. “I was back in the stairwell,” he recalls. “I would re-experience the collapse. One time, the nightmare was so vivid I said, I got to talk to someone about this .”

Still, the morning before his first meeting, he asked his wife, “Do you think I really need counseling?”

“I didn’t want him to go for me,” says Judy Jonas, his wife of 22 years. “I wanted him to realize he needed to go.”

Eventually, his wife went, too. So did his son, after he refused to go to baseball camp even though it was at the field across the street from their house.

Lim has spent two years in therapy. “Without counseling, I don’t think I could be here now,” he says at the police station at La Guardia airport, his new dog asleep at his feet. “The biggest thing for me was accepting that I really did miss my partner.” He meant Sirius, the yellow Lab that lived with his family. On September 11, Lim had put Sirius in his cage, intending to return. “He’s just a dog. But I had to admit to myself that I really missed him a lot, that I felt guilty about leaving him there.” The words “leaving him there” affect Lim. “I meant to come back,” he says sadly. “Things didn’t work out.”

Komorowski, now 40, mostly felt the effects at home. He lives in Massapequa Park, a firemen’s town—streets have been renamed for dead firemen—on a lovely middle-class block where the split-level homes are identical, though Komorowski’s is probably the only one where a dust-encrusted fireman’s helmet, the one he was wearing September 11, sits in a glass case on a coffee table.

Summers, Komorowski, his wife, and their two daughters spend a lot of their time outside. One afternoon, Jennifer, Komorowski’s wife of five years, puts hamburgers on the grill. His 4-year-old stands on her chair at the table with the American-flag tablecloth, and with two hands squeezes ketchup out of a plastic jar.

Unfortunately, Komorowski can’t dependably relax enough these days to concentrate on the kids. “I can’t always play with them without losing focus,” he explains. “I kind of lose interest in what I’m doing.” Komorowski seems to accent each word equally—like the actor Christopher Walken—which gives his intense emotions a strange, deliberate quality.

“Sometimes,” he continues, “I cry for no reason,” like when he’s watching a commercial on TV. “When I say no reason, I know it’s 9/11, but there’s nothing in the day that sets it off. It’s just that you’re at a saturation point.” Sometimes, he gets dizzy or lightheaded. “From anxiety, I’ve had shortness of breath and I have to sit down and regroup,” he explains. He sometimes finds that noises spook him, or being in an elevator or on a subway. Once, a few days after September 11, he was jolted awake in the middle of the night; his body shook uncontrollably for twenty minutes. “You got to constantly talk to yourself,” he says. “ ‘I’m not at the World Trade Center. I’m not at 9/11.’

“The image of the staircase is very vivid in my mind,” he continues, “and the image of the debris field is very vivid. I think about that a lot. I’m thinking about that now.” He closes his eyes, rubs his temple, trying, he says, to make himself feel better. “Sometimes the images will come and I will dwell on them,” he says. “That’s when you know, Okay, this is going to be a spiral down .”

His wife has to urge him, Don’t feed into it. “If he talks about everything that happened that day, it just gets worse,” she says. “So we refocus.”

Therapy helps. Still, it can feel like another symptom. “Constantly going over [that day], thinking about it,” says Komorowski.

Surviving is a freakish experience. These people really should be dead. (“That’s the day I should have died,” Buzzelli says sometimes.) And since they’re not, then they should be thankful. They lived a miracle. They should walk through life full of joy. And yet these people—and their families sometimes more so—seem afflicted by a persistent guilt, guilt for having lived.

Louise Buzzelli is vivacious and tiny, an inch or so over five feet. On September 11, 2001, she was seven months pregnant. Getting pregnant had been hard, and when it finally happened, she’d been ecstatic. “I lost my own mother at a young age,” she says. “I’ve always wanted that mother-child relationship again.”

After speaking to her husband that morning and learning that he was about to walk down from the 64th floor, Louise hung up and turned to the TV. Twenty minutes later, she watched as the North Tower collapsed. “Everything inside of me just drained,” she says. “I watched my husband die right in front of my eyes.” Louise walked outside toward the pool. How am I going to bring up this baby? I can’t do this alone. I can’t do this , she thought.

When Buzzelli called at 3:30 everything changed, though not as she’d expected. Soon, she’d know that he’d somehow landed safely in the midst of acres of destruction, a lone soul dropped to safety on a concrete slab. “I heard his voice,” she says, and felt “an explosion of emotions.”

She had her husband back, and yet—it was the oddest thing—she couldn’t quite seem to feel the uncompromised happiness she’d expected. For Louise, those few hours when she was a pregnant wife with a dead husband wouldn’t leave.

Louise, blonde and now with a 21-month-old daughter named Hope, sits on the floor of the family room and talks about her complicated state. “It’s like you feel guilty about feeling good,” she says. The guilt concerned the widows. Some of the other wives are familiar with the feeling. It was as if the widows’ terrible sorrow accused them. Their inexplicable good fortune seemed a source of embarrassment. “You apologized for me being alive,” Jonas told his wife at one point. (She didn’t think she had.)

For Louise, the guilt crystallized one day at the supermarket, where she spotted a magazine cover of the widows who’d been pregnant on September 11. There were 101 of them; for a few hours, Louise had been 102. “It overwhelmed me,” she says. “How do I go on as the person I was before—that happy-go-lucky, that high-spirited person—knowing that these mothers are out there? I know what they felt like, and it was only for that one day.”

Louise felt she had to do something for the mothers. She wrote a song and recorded it as a CD—she has a lovely voice. She set off to sell it to raise money for their new Song for Hope Foundation ( www.songforhope.com ), named for their new daughter. To pursue her plan, Louise wanted to get publicity. The media, though, wanted to talk to her husband, to hear his story.

And that was the last thing Buzzelli wanted. In his family room, Pasquale sits in a club chair, in the same position, he points out, as he’d found himself on that slab of concrete. He’s twenty pounds heavier. It had taken him a long time to decide to talk about this again, and he speaks haltingly. “When I think about that day, I start to feel the emotions I felt that day,” he says, and that’s not good. “I can’t go through a whole day like that,” he says. “I need to forget. And I can’t forget.”

For a long time, Buzzelli wanted to be left alone—most of the survivors did. Billy Butler, who got himself a tattoo—a tattered flag and the date, 9-11-01—would go upstairs when he got home, turn on the TV, ignore his wife and kids. “It’s not a deliberate self-absorption,” explains Komorowski. “You’re just trying to battle to keep yourself together on a day-to-day basis.”

Buzzelli didn’t really want to talk at all. “I was so emotionally drained,” he says, “I just wanted to sit down, watch a movie, not talk to anyone.” He’d started seeing a therapist. “So I can move on,” he says. “And here I was being brought back by Louise. It’s reliving the day you almost died, should have died.”

Louise couldn’t quite fathom her husband’s change. “He always had something going on, some plan,” she says. “It’s not like that anymore.”

“I’m more relaxed,” says Buzzelli.

“More passive,” says Louise. “He’s more like, ‘Whatever, if it happens, it happens.’ ” Louise felt otherwise. She seemed energized by her new mission. She says, “It made me feel alive again.”

Their lives moved in different directions. Was it possible that, against all odds, her husband had survived only to have his marriage come apart? “Pasquale and I weren’t really communicating anymore,” says Louise. “We were disagreeing on so many things. We were not the same couple anymore. It was almost tearing us apart.”

Still, Louise was intent on organizing a Mother’s Day celebration for these new mothers and recent widows. “I needed to know that these mothers knew that somebody felt what they felt,” she says. She set out to track them down. “Every time I got to speak to or e-mail one more,” she says, “it was like, okay, I could breathe a little easier.”

Louise knew that thinking about September 11 pained Buzzelli. Oh, my God, I’m killing my husband , she thought. Still, she wanted him to tell his story to the media, to help publicize the foundation. “We’re together, we have a baby,” she pleaded with him. “These people don’t have that.”

“I wanted to do it,” Buzzelli says. He wrestled with her request. He didn’t think of himself as the type to mope. He couldn’t remember being afraid of anything. “She felt it was something she had to do, but it was painful to talk about,” Buzzelli says. He decided to give her a day. “I felt like, ‘Who am I to say no?’ ” he says. There were a couple newspaper articles, and Channel 11 did a nice report. Then Buzzelli said, “Don’t ask me to do another thing.” Louise remembers, “Peter Jennings called. Pasquale didn’t talk to him.”

Louise raised $10,000 and distributed it this year at a Mother’s Day luncheon. She gave 50 mothers $200 in the name of their babies, a nice gift, and, for Louise, a tremendous relief.

“When she had her Song for Hope thing, it was a really nice day,” Buzzelli says. “I couldn’t be there. I felt like I would make the mothers feel bad. How can they not feel bad?”

On stairwell B, after the noise of collapse—one fireman said he heard each floor come down, like a drum roll—the narrow space was quiet and almost completely dark. Dust and ash clogged the air. The walls—when flashlights were retrieved—appeared mostly intact, which made the space, as one recalls, “claustrophobic and dreamlike and terrifying.” One fireman shimmied out of his coat and laid it on top of Harris. There wasn’t much talk. A couple guys tried a door. Some stayed on their backs, lethargic, half buried, worried that any movement would trigger a secondary collapse. Entombed was the word that came to Jonas’s mind. He figured that hundreds of feet of rubble lay on top of them.

The highest-ranking officer in the stairwell was Chief Richard Picciotto. After helping clear the nonambulatory from higher floors, Chief Pitch, as he was called, had given the order to evacuate. Then he’d raced down the stairs. He’d landed on his back, a couple floors below Jonas, buried under half a foot of pebbles and dust. Picciotto and Jonas had been pals for years. They lived a few minutes from each other and had studied together for Fire Department tests. “It’s better to die with a friend than a stranger,” Picciotto would later say.

It wasn’t an idle thought. Above and below them, they knew, firemen were dying. They knew that because they broadcast their final words over their walkie-talkies. Chief Richard Prunty said he was in the lobby, pinned under an I-beam, and losing consciousness. “Tell my wife and kids I love them,” he said into his radio. Jonas picked up a Mayday from the lieutenant of Ladder Five, who reported that he was in Stairwell B on the 12th floor. Jonas had passed him on the way down, helping a civilian. “I’m trapped and I’m hurt bad,” he said. Jonas, who was on the fourth floor, tried to climb the stairs but couldn’t ascend more than a floor, and in any case, as he’d later learn, the stairwell had no 12th floor. “I’m sorry, I can’t help you,” he radioed back.

Meanwhile, Jonas and Picciotto radioed their own Maydays. Brother firefighters picked up the distress calls. “We’re in the North Tower,” Jonas radioed. “Where’s the North Tower?” came the reply. Eventually, a slender shaft of light saved them. It would turn out that the stairwell—five flights of it—hadn’t been completely buried. It poked up through the rubble like a chimney. They’d been entombed as much by the smoke and ash clouds as by the debris, and when light broke through an opening in the top of the stairwell, they followed it out, Picciotto in the lead.

Thirteen people would eventually climb out. (Harris would be lifted.) More than 100 floors had fallen on top of them, and after a few hours, this group simply walked out. They were a fortunate handful united by a singular experience. Then, eight months later, Picciotto’s book came out. (“We should write a book,” he’d told his friend Jonas a few days after they climbed out. “Write a book?” Jonas replied. “I can barely get out of bed.”) Picciotto’s Last Man Down became a best-seller.

It would also end his friendship with Jonas—“It’s a very bad book,” says Jonas—and whatever camaraderie he shared that day with the others from Ladder Six. “We don’t speak to him,” says Komorowski. “Liar,” Butler wrote in his copy of the book.

In the scheme of things, this is perhaps a minor intramural scrap. Still, in a sense, history is at issue—who gets credit or blame, and also, maybe, who sleeps well. And so, fueled no doubt by the potent emotions that swirl around that day, there is competition over details—who spotted the shaft of light, who took roll call—which adds up to who was a hero that day. (“It depends who you ask,” says Picciotto.)

“It was part of my personality to take charge of a situation,” Picciotto writes. “I’d never been the type to sit idly by while someone else called the shots, and I wasn’t about to start now.”

“Picciotto was the highest-ranking guy, but he was not the commanding officer. He was doing nothing. He was balled up in a corner,” says Jonas.

In his first days at home, when Picciotto, now 52, couldn’t sleep, he dictated his memories into a tape recorder. Writing the book, and its success, probably helped Chief Pitch get clear of the worst effects. “It was cathartic,” he says. The book also provided a financial cushion. Picciotto retired after almost 30 years as a firefighter.

The book is an account of Picciotto’s day, and he did a lot that day. Yet in some instances, he seems to have gotten carried away. He writes that he matched Josephine Harris with Jonas’s company, Ladder Six. “There was something about Josephine that seemed deserving of my extra special attention,” he writes. But Harris doesn’t remember Chief Pitch. And Jonas and Butler know they came upon Harris alone in the stairwell. Picciotto also writes that he was running the show in Stairwell B. But many of the firemen seem to have taken their orders from Jonas that day. “He writes about us like we’re lemmings, like Please, Rich Picciotto, save us ,” says Jonas.

The book, plainspoken, conversational, is self-glorifying, which may be the source of the trouble. Firefighters live by codes. When, finally, the men trapped in Stairwell B raised rescuers on the radio, the response was, “Brother, we’re coming for you.” By the code, firefighters are brothers. Picciotto’s book is a story of an individual, mainly, rather than of a group, which goes against the grain. “Other people tell you you’re a good firefighter,” explains one department official. “You don’t claim that yourself.”

Clearly, however heroic he was that day, Picciotto was other things, including frightened. Picciotto, the first to escape, tied off his end so others could use the rope, then swiftly “opened up a good deal of distance between myself and the rest of the pack,” he writes. “That was okay. In my head, it had moved from being a leadership situation … to being a question of survival… . My focus shifted … to getting the hell out of there.”

Jonas says, “We would have taken his actions to the grave with us,” which is what the code dictates. But Picciotto violated the code. “He started taking credit for the things that we did,” says Jonas.

Picciotto doesn’t think that’s what he did. “If you ask ten different witnesses to an accident, each has a different story,” he says. As far as Harris, he says, “I wasn’t specifically helping her; I was organizing moving a lot of people.” The conflict bothers him. He hopes to make up with Jonas eventually. “It’s a shame. He doesn’t live far from here,” he says.

These days, Picciotto says, his publisher has been after him to write another book, but he isn’t interested. “I want to enjoy life,” he says. “I don’t know how to go about doing that.” He misses firefighting, a career he loved, and the camaraderie of the firehouse: “I was happier then,” he says. The Fire Department plans to reunite those trapped in Stairwell B for a counseling session, except for Picciotto, who, in this group, has become odd man out.

Louise and Pasquale Buzzelli’s relationship has gotten back on track; they’ve got Hope, a toddler now and a great source of happiness. Many relationships hit a rocky patch at first—“We had difficulty,” Diane Butler says sharply—then got better and often deeper. The disaster brought each firefighter closer to his wife. “We’re more tender with each other now,” says Debbie Picciotto. Husbands, in particular, have a new appreciation for their partners. One day, Billy Butler forgot to pick up a kid at school—he forgets a lot these days. Later, Diane told him pointedly, “Get back in the game.”

“She’s really been the backbone,” he says.

But talk to these survivors for any length of time, and you wonder: Why hasn’t relief followed good fortune? As Louise puts it, “Why aren’t we happy? As opposed to feeling bad and feeling that at any moment it could totally be gone again?”

In fact, many of the survivors are still gripped by the event. If not careful, many find themselves back there in the thick darkness of the stairwell, breathing the sooty air. Prunty dies again over their radios. Those few hours are relentless; they won’t let go. “Our personalities have changed. September 11 affected every part of our lives, the way we interact with each other, with our children, with our friends,” Jennifer Komorowski says wearily one sunny day on her backyard deck.

“Everything seems more subdued, toned down. That sadness in your heart that you felt that day, that week, it kind of hasn’t gone away.”

Many aspects of life seem just fine. Buzzelli is back at the office. He works hard, though he can’t shake the feeling that he’s lost time. “It’s two years later, and everything is the same, if not worse,” he says. Lim, reassigned to La Guardia, still misses his old partner—he can admit that freely now—but he has a new dog, a black Lab named Sprig. Harris returned to work after less than a month off. Butler and Komorowski earned promotions to lieutenant, which keeps them focused. (Though Butler still hides from the sound of thunderstorms, and Komorowski still has to reassure himself in elevators.) Captain Jonas was made a chief—leading his men out of the Trade Center was his last act as a captain. His nightmares come less frequently now, and his son, after considerable coaxing, agreed to go to Boy Scout camp this summer. But just being normal—or what the Fire Department calls the “new normal”—takes work. “Nothing seems easy anymore, or clear-cut. We got to think out everything,” says Jonas. “Are the kids going to be okay? Are we going to be okay?”

“I wish we could just go back to the people we were. We used to be great fun,” says Jennifer Komorowski.

Matt Komorowski recently asked his therapist about the chances of getting it all back. The therapist assured him—these guys quote their therapists now—that over time, a person usually returns to the person he was before a trauma. The answer surprised Komorowski. “I’d like that,” he says, “but I’m not there yet.”

The one thing that takes these guys away from that day and its mysterious echoes is, oddly, a good fire, which is what they call a fire where they get in, help the people, and get out without injury. “When I go to a fire, I don’t really have the time to think about 9/11,” says Komorowski. “There is no dizziness. No shortness of breath. I can’t explain it, but that’s the way it is.” Maybe it’s that work means making a bad situation better, a luxurious feeling. Jonas concurs. “I’m happiest—at ease, comfortable, anxiety gone—immediately after a fire.”

Most viewed

- The Best, Worst, and Weirdest Met Gala 2024 Looks

- A Complete Track-by-Track Timeline of Drake and Kendrick Lamar’s Feud

- Tyla Won the Red Carpet Wearing Sand

- Cinematrix No. 53: May 8, 2024

- Met Gala 2024: All the Looks

- The Package King of Miami

- The Last Thing My Mother Wanted

What is your email?

This email will be used to sign into all New York sites. By submitting your email, you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy and to receive email correspondence from us.

Sign In To Continue Reading

Create your free account.

Password must be at least 8 characters and contain:

- Lower case letters (a-z)

- Upper case letters (A-Z)

- Numbers (0-9)

- Special Characters (!@#$%^&*)

As part of your account, you’ll receive occasional updates and offers from New York , which you can opt out of anytime.

- Buy Paper back in Store

- Buy on Amazon e-book

- Photo Album & Links

The True Stroy of the 9/11 Surfer The story of a miracle... WE ALL FALL DOWN: THE TRUE STORY OF THE 9/11 SURFER is authored by 9/11 survivor Pasquale Buzzelli and his wife Louise, co-written by Joseph Bittick, and edited by Autumn Conley. The memoir/biographical work tells the story of the "9/11 Surfer," survivor of the collapse of the WTC North Tower, and his wife Louise Buzzelli, detailing the struggles of the couple on that fateful day, as well as in the aftermath of the disaster. Pasquale Buzzelli, a structural engineer with Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, was in his office on the 64th floor of the North Tower when the 9/11 attacks began. He spoke to his pregnant wife several times on the phone before he began his evacuation after the South Tower fell. Sensing something ominous, Pasquale crouched down and huddled into a corner of the stairwell as the 110-story tower came crashing down around him. He survived the tower collapse and woke up in the open air hours later on "the pile," a stack of debris some 7 stories high. The firemen who rescued Pasquale shared his remarkable story of survival with the media, as did others who cared for him that day; however, dealing with PTSD and survivor's guilt and trying to move past it, Pasquale Buzzelli did not come forward at that time, and his captivating story, the tale of the "9/11 surfer" became a myth, an urban legend, and an enigma that gave rise to much speculation. Now, 11 years later, Pasquale Buzzelli recalls the events of 9/11/2001 in vivid detail of falling and "surfing" during the collapse of the North Tower.

9/11 Anniversary

Rescued from twin towers, survivor's guilt 10 years later, ten years later, meets with firefighters who saved him, by andrew siff • published september 7, 2011 • updated on september 8, 2011 at 4:58 pm.

Thousands of people went into the twin towers on Sept. 11 nearly 10 years ago, and Pasquale Buzzelli was one of the lucky few who made it out, surviving the collapse of the north tower before he was rescued by firefighters.

When the first plane hit the north tower at about 8:46 a.m., Buzzelli was in an elevator, going up.

"I felt the elevator shake violently and actually drop," he recalled, in an interview with NBC New York.

Buzzelli, an engineer with the Port Authority, was on his way to his 64th floor office. He called his wife, who was seven months pregnant with their daughter, and tried to sound as calm as possible.

"I said 'Louise, don't be alarmed, I'm ok,'" he said.

Buzzelli got out of the elevator around the 44th floor, and started taking the stairs.

At home, his wife couldn't relax. The smoky fire she watched on her TV screeen soon became the most horrifying image she could imagine.

Mister Softee app allows ice cream lovers to track the nearest truck

Organized retail theft ring that targeted Macy's, other retailers is charged in New York

And then the tower collapsed.

"I just prayed that he wouldn't suffer," said Louise Buzzelli.

She was convinced he was dead. So was he.

"I curled up right in the corner in the fetal position and I thought, 'there must be something heavy falling down through the stairs,'" he said.

As the tower around him collapsed, Stairwell B became an unexpected harbor. But Buzzelli didn't know it yet.

"I remember saying 'I can't believe this is how I'm going to die. This is how it's going to end. Please God, take care of my wife, my unborn child,'" he recalled.

But somehow, Buzzelli's cascade from about the 22nd floor ended with him perched atop a crumbled pile of debris, very much alive.

"He was trapped," said Fire Lt. Mike Lyons. "He was isolated on a slab of concrete, 4- by 6 feet. In any of four directions he had a long way to go down."

Lyons and a team of other firefighters couldn't believe that in a sea of wreckage they'd discovered a survivor.

"It was amazing," said firefighter Michael Morabito. "Especially the way he was sitting. The sky was blue and he was just untouched in all that destruction."

The first responders crafted a harness out of rope. They draped the sling around Buzzelli and lowered him to the ground.

He was treated at St. Vincent's for a broken ankle before he was allowed to go home to his wife and friends in Bergen County.

"Every day is a gift," said his wife.

But the next 10 years weren't easy. The Buzzellis have grappled with the reality that thousands died and he didn't.

"A little bit of survivor's guilt," said Buzzelli. "I should be happy, this tastes better -- and then you feel guilty about surviving. You think about the dads that didn't see their daughters being born."

What's helped, said Louise Buzzelli, is that daughter Hope, now nearly 10, has become friends with other children of 9/11.

The Buzzellis' younger daughter, Mia, is 6. The family has even written a book called "We All Fall Down," inspired by the children's game Ring Around the Rosie, and has a website about their story: http://911survivor.com .

Hope, an aspiring artist, drew the book's cover. "I think it's a picture of peace and freedom, almost," she said. "There are kids in red and white and blue holding hands, kind of like a symbol of peace in a way."

As for having a father present when the events of 9/11 nearly made that impossible, Hope Buzzelli had this observation:

"To me it's kind of sad and happy. I feel bad for everyone else that lost important people in their life, but I'm happy my Dad is alive."

Le 11-Septembre, 20 ans plus tard La journée qui a changé le monde

PHOTO JIM COLLINS, ARCHIVES AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

(New York) Il y a 20 ans aujourd’hui, les pirates de l’air d’Al-Qaïda lançaient une attaque terroriste sans précédent aux États-Unis. L'opération, réglée au quart de tour, a été planifiée dès 1996 dans les grottes de Tora Bora, en Afghanistan. C’est là que Khaled Cheikh Mohamed, ingénieur pakistanais ayant fait ses études aux États-Unis, a fait part à Oussama ben Laden de son plan: lancer des avions de ligne contre des objectifs américains. Le plan a séduit le chef d’Al-Qaïda, qui y a vu un moyen de forcer les États-Unis à détaler du Moyen-Orient. Voici comment la journée s’est déroulée, d’heure en heure.

Dans un ciel d’un « bleu incroyable », comme le chantera Bruce Springsteen, le vol 11 d'American Airlines décolle de Boston. Tout vire au cauchemar environ 15 minutes après son départ à destination de Los Angeles.

L’agente de bord Betty Ang Ong prévient le personnel au sol que le cockpit n’est plus accessible.

PHOTO TIRÉE DE WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Je pense que nous sommes en train de nous faire pirater.

L’agente Betty Ang Ong, à l’aide d’un téléphone de bord

L’un des passagers, David Lewin, qui a servi sous le drapeau israélien pendant quatre ans, vient d’être poignardé par l’un des cinq pirates de l’air à bord, probablement Satam al-Suqami. Au total, 92 personnes se trouvent dans l’avion.

Quatre minutes avant l’appel de l’agente de bord, le vol 175 de la compagnie United Airlines a décollé de l’aéroport de Boston en direction de Los Angeles. Cinq autres pirates de l’air sont à bord avec 60 autres personnes.

Cinq minutes après l’appel, c’est au tour du vol 77 d’American Airlines de prendre la route de Los Angeles. Au départ de l’aéroport international Dulles de Washington, cinq autres pirates de l’air sont présents dans l’avion avec 59 autres personnes.

L’Égyptien Mohamed Atta, chef des pirates de l’air, diffuse accidentellement du cockpit de l’avion du vol AA11 un message aux contrôleurs aériens qu’il destinait aux passagers et aux membres du personnel de bord :

IMAGE TIRÉE DE WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Nous avons des avions. Restez tranquilles et vous serez OK.

Mohamed Atta

Il s’écoule sept autres minutes avant que la Garde nationale aérienne ne soit mobilisée pour suivre le Boeing 767 à bord duquel Atta se trouve.

Un quatrième avion s’envole pour la côte Ouest, au départ de l’aéroport international de Newark avec 37 passagers, dont 4 pirates de l’air, et 7 membres du personnel à bord. C’est le vol 93 de United Airlines.

Le plan de Khaled Cheikh Mohamed, « cerveau » des attentats du 11 septembre 2001, est en marche.

Khaled Cheikh Mohamed

George W. Bush ne se doute de rien. Fidèle à l’image du conservateur compatissant qu’il veut se donner, le président républicain visite ce jour-là l’école élémentaire Emma E. Booker à Sarasota, en Floride, où les élèves sont majoritairement noirs et hispanophones.

Quand le vol AA11 s’encastre dans la tour nord du World Trade Center, créant une énorme boule de feu entre les 93 e et 99 e étages, il est en train de s’entretenir avec la directrice de l’école, Gwen Tose-Rigell, et des membres de son personnel. Environ quatre minutes plus tard, Karl Rove, conseiller présidentiel, l’informe qu’un avion s’est écrasé dans l’une des tours jumelles. Il laisse entendre qu’il s’agit probablement d’un accident impliquant un petit appareil à hélice. Et la visite du président se poursuit dans la classe de deuxième année de l’enseignante Sandra Kay Daniels.

« L’Amérique est attaquée »

PHOTO SETH MCALLISTER, ARCHIVES AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

Le vol UA175 s'apprête à percuter la tour sud du World Trade Center

Le vol UA175 percute la tour sud du World Trade Center, entre les 77 e et 85 e étages, rendant inaccessibles deux des trois escaliers d’urgence du gratte-ciel. Deux minutes plus tard, Andrew Card, chef de cabinet de la Maison-Blanche, entre dans la classe de Sandra Kay Daniels et chuchote à l’oreille de George W. Bush : « Un deuxième avion a frappé la deuxième tour. L’Amérique est attaquée. »

PHOTO ARCHIVES AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

« L'Amérique est attaquée », dit à l'oreille de George W. Bush son chef de cabinet Andrew Card.

Les caméras de télévision captent le choc et la confusion du président, qui reste cloué sur sa chaise devant des élèves qui se livrent à un exercice de lecture intitulé The Pet Goat . Au fond de la classe, le porte-parole de la Maison-Blanche Ari Fleischer brandit une feuille sur laquelle il a écrit en grosses lettres : « NE DITES RIEN POUR L’INSTANT. »

Le président des États-Unis ne pipe mot sur ce qu’il vient d’apprendre, se contentant d’écouter ou de commenter l’exercice de lecture pendant environ 10 autres minutes.

Il prononce ses premières paroles en public sur les attentats du World Trade Center dans le gymnase de l’école : « Aujourd’hui, nous avons vécu une tragédie nationale. J’ai ordonné que toutes les ressources du gouvernement fédéral soient affectées à l’aide aux victimes et à leurs familles, et qu’une enquête approfondie soit menée pour traquer et trouver ceux qui ont commis cet acte. »

Le vol AA77 s’écrase sur le Pentagone, siège du département de la Défense, tuant 189 personnes sur le coup. Vingt-six minutes plus tard, le vol UA93 finit sa course dans un champ de la ville de Shanksville, au sud-est de Pittsburgh, après une rébellion de passagers menée par Todd Beamer, 32 ans, qui a lancé la charge contre les pirates de l’air avec ces mots : « Let’s roll » (« On y va »).

Après l’attaque du World Trade Center, le service d’incendie de New York (FDNY) orchestre la réponse la plus importante de son histoire, mobilisant toutes les ressources dont il dispose dans les cinq arrondissements de la ville. Des milliers d’autres premiers répondants et responsables de gouvernements locaux ou d’agences fédérales arrivent également sur les lieux de la catastrophe.

Mais les communications sont difficiles, voire impossibles entre les intervenants. Dans le hall de la tour Nord, le chef du FDNY, Thomas Von Essen, se plaint d’en savoir moins sur ce qui se passe que les gens dans la rue ou ceux qui voient à la télévision les tours enfumées et les images en boucle des avions qui les percutent.

Plus de 1000 personnes sont prises au piège au-dessus des zones d’impact des tours Nord et Sud. Au fur et à mesure que la fumée et la chaleur s’intensifient, les appels au 911 deviennent plus désespérés. Coincée au 83 e étage de la tour Sud, Melissa Doi, gestionnaire financière de 32 ans, dit à une répartitrice du 911 :

« C’est très chaud, je ne vois plus l’air… Je ne vois que de la fumée.

— OK, chère, je suis désolée, restez calme…

— Je vais mourir, n’est-ce pas ?

— Non, non, non, dites… dites vos prières.

— Je vais mourir. »

Dehors, les premiers répondants voient des personnes tomber ou sauter des plus hauts étages des tours, en tenant parfois la main d’un ou d’une collègue. En traversant West Street, une responsable du FBI, Wesley Wong, entend un pompier lui dire : « Attention aux corps qui tombent. » Elle ne comprend pas ce qu’elle vient d’entendre jusqu’à ce qu’un autre pompier lui crie, alors qu’elle se trouve près de l’une des tours : « Courez ! En voilà un ! »

PHOTO RICHARD DREW, ARCHIVES ASSOCIATED PRESS

Elle fige, regarde en l’air et voit un homme, vêtu d’un pantalon bleu, d’une chemise blanche et d’une cravate, les jambes et les bras écartés, en plein vol.

Les plus chanceux réussissent à sortir des tours en descendant les marches des escaliers d’urgence accessibles, où la fumée se mêle à l’odeur de kérosène. Ils croisent des pompiers qui montent en transportant leur lourd équipement. Dans la tour Nord, Jean Potter, employée de Bank of America, pose une main sur le bras de Vinnie Giammona, capitaine du FDNY.

« Faites attention », lui dit-elle en pensant qu’il ne parviendrait jamais à sortir vivant de là.

« Où est passée la tour ? »

Beverly Eckert parle au téléphone avec son mari, Sean Rooney, qui se trouve dans les bureaux de la compagnie d’assurances AON, au 98 e étage de la tour Nord. Elle entend de façon distincte une forte explosion, qui se prolonge pendant plusieurs secondes. Puis elle discerne un craquement, suivi par le bruit d’une avalanche et une dernière respiration de son mari au moment où le plancher se dérobe sous ses pieds. Elle répète son nom au téléphone encore et encore.

De Brooklyn, Monica O’Leary, qui a déjà travaillé au One World Trade Center, répète à son voisin John, en observant une scène qu’elle n’aurait jamais pu imaginer : « Où est passée la tour ? Où est passée la tour ? »

PHOTO GULNARA SAMOILOVA, ARCHIVES ASSOCIATED PRESS

Effondrement de la tour Sud

En ondes depuis la première attaque de la journée, le chef d’antenne d’ABC Peter Jennings choisit de ne rien dire pendant que les téléspectateurs peuvent voir à l’écran une image qui dépasse tous les mots du dictionnaire : la tour sud du World Trade Center est disparue sous un nuage de poussière et de fumée qui se répand bientôt partout dans le sud de Manhattan.

La tour Nord s’écroule à son tour, ajoutant à l’horreur dantesque de la journée.

Plus de 2600 personnes viennent de mourir sur le site du World Trade Center. Figurent parmi les victimes 343 pompiers de New York, 37 policiers de l’Autorité portuaire, 23 membres des forces policières de la ville (NYPD) et une douzaine d’autres premiers répondants et représentants d’agences gouvernementales.

Un étrange silence succède à l’effondrement des tours, semblable à celui qui suit les tempêtes de neige à New York. Mais au lieu d’être ensevelis sous des couches de flocons blancs, les rues, les voitures et même les murs des immeubles sont recouverts d’une épaisse couche de cendres grises.

Des cendres enveloppent aussi les humains qui ont réussi à s’éloigner à temps des tours jumelles ou à s’extirper de ses débris. Des cendres qui leur donnent des allures de zombies. Le maire de New York, Rudolph Giuliani, et ses principaux collaborateurs se trouvent parmi eux. Ils sont à la recherche d’un endroit où établir un poste de commandement. Ils ne peuvent utiliser ni le Centre de commandement d’urgence de la Ville, situé malencontreusement au 23 e étage du Seven World Trade Center, ni le quartier général du NYPD, coupé du monde en raison de problèmes de communication.

Après avoir arpenté plusieurs pâtés de maisons, ils s’installent dans un poste de pompiers de Greenwich Village. Andrew Kirtzman, journaliste de la chaîne d’information NY1, est avec eux. Rudolph Giuliani l’a invité à se joindre à son groupe, oubliant la biographie sans complaisance que Kirtzman a fait paraître à son sujet sous le titre Rudy Giuliani : Emperor of the City .

Le journaliste connaît les nombreux défauts du maire, mais il constate qu’il est, ce jour-là, le plus calme du groupe. Ni peur ni panique n’émanent de sa personne. La ville, le pays, le monde sont à la recherche de leadership depuis le début de la journée. En l’absence du président, isolé volontairement pour sa protection, Giuliani répond à l’appel.

Aujourd’hui est évidemment l’un des jours les plus difficiles de l’histoire de la ville.

Le maire Giuliani, d’une voix posée, lors de sa première conférence de presse de la journée

« La tragédie que nous vivons en ce moment est quelque chose que nous avons vu dans nos cauchemars, poursuit-il. Je suis de tout cœur avec toutes les victimes innocentes de cet acte de terrorisme horrible et vicieux. Et notre objectif doit maintenant être de sauver autant de vies que possible. »

Un journaliste lui pose la question inévitable : combien de vies perdues ? Le maire lève les yeux, conscient que parmi les téléspectateurs de ce point de presse en direct se trouvent les mères, les pères, les conjoints, les amoureux et les enfants de ceux qui travaillaient dans les tours détruites.

« Le nombre de victimes sera plus grand que ce que quiconque d’entre nous peut supporter en fin de compte », dit-il.

Air Force One quitte la base aérienne d’Offutt, au Nebraska, pour rentrer enfin à Washington. Jusque-là, les Services secrets et les principaux conseillers de George W. Bush lui ont interdit de retourner à la Maison-Blanche. Trop risqué dans les circonstances.

PHOTO ERIC DRAPER, ARCHIVES AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

George W. Bush à bord d' Air Force One , le 11 septembre 2001

Depuis sa visite à l’école élémentaire Emma E. Booker, le président des États-Unis a ainsi passé la journée dans les airs, où il ne recevait que des informations parcellaires des attentats visant son pays, ou sur des bases aériennes, d’abord celle de Barksdale, en Louisiane, puis celle d’Offutt, qui est dotée d’un bunker de commandement souterrain.

C’est à cet endroit qu’il a dirigé une vidéoconférence au cours de laquelle George Tenet, directeur de la CIA, lui a dit : « Monsieur, je crois que c’est Al-Qaïda. »

Et c’est de cet endroit que la Maison-Blanche s’est préparée pour que le président s’adresse à la nation plus tard en soirée. Mais George W. Bush a insisté pour regagner Washington. Cette fois-ci, il a fini par surmonter la résistance de son entourage.

Le Seven World Trade Center, édifice de 47 étages situé à un jet de pierre des tours jumelles, s’effondre à son tour, des heures après avoir été évacué. Dépassé par les évènements de la journée et aux prises avec une faible pression d’eau, le FDNY a décidé de le laisser brûler sans intervenir.

Pendant le reste de l’après-midi et jusqu’à la fin de la soirée, les recherches se poursuivent à New York pour trouver ceux qui manquent à l’appel. Munis de simples seaux en plastique, des volontaires se joignent aux premiers répondants, commençant la tâche titanesque de déblayer ce qu’on appelle déjà « The Pile » (« le tas ») mais pas encore Ground Zero, afin de trouver des survivants sous les décombres fumants.

Il y en a. Pasquale Buzzelli, ingénieur de l’Autorité portuaire de New York, est repéré par des pompiers qui réussissent à l’extirper d’une cavité à l’aide d’une corde et d’une civière. À l’ambulancier qui lui demande où il a mal, l’homme de 34 ans répond :

Avant de parler de ça, j’ai besoin d’un téléphone. Ma femme est à la maison. Elle est enceinte de sept mois. Elle sait que je n’étais pas sorti de la tour.

Pasquale Buzzelli, rescapé

À Union Square Park et dans beaucoup d’autres endroits de Manhattan, des centaines, puis des milliers d’affiches photocopiées apparaissent, identifiant les personnes qui n’ont pas encore donné signe de vie. Elles serviront moins à combler les espoirs de leurs proches qu’à mettre des visages et des noms sur une tragédie innommable.

Un grand mouvement de sympathie, de solidarité et de patriotisme prend alors forme, lequel se manifeste notamment par les files de personnes prêtes à donner du sang aux hôpitaux qui en réclament. Dans le sud de Manhattan, les gens applaudissent les pompiers et les policiers qui se dirigent vers les ruines du World Trade Center. La bannière étoilée apparaît aux fenêtres.

« Notre nation a vu le mal »

George W. Bush s’adresse enfin à la nation traumatisée et endeuillée du bureau Ovale de la Maison-Blanche.

« Aujourd’hui, notre nation a vu le mal, le pire de la nature humaine. Et nous avons répondu avec le meilleur de l’Amérique – avec l’audace de nos secouristes, avec la sollicitude des étrangers et des voisins qui sont venus donner leur sang et aider de toutes les manières possibles. »

Il conclut ainsi : « C’est un jour où tous les Américains, de tous les horizons, s’unissent dans leur détermination pour la justice et la paix. L’Amérique a déjà fait face à des ennemis, et nous le ferons cette fois-ci. Aucun d’entre nous n’oubliera ce jour. Pourtant, nous allons de l’avant pour défendre la liberté et tout ce qui est bon et juste dans notre monde.

« Merci. Bonne nuit, et que Dieu bénisse l’Amérique. »

PHOTO DOUG KANTER, ARCHIVES AGENCE FRANCE-PRESSE

The Only Plane in the Sky : An Oral History of 9/11 , de Garrett Graff, éditions Avid Reader Press/Simon & Schuster, 2019

102 Minutes : The Untold Story of the Fight to Survive Inside the Twin Towers , de Jim Dwyer et Kevin Murphy, éditions Times Book/Henry Holt & Company, 2005

9/11 Memorial : « September 11 Attack Timeline »

'9/11 Surfer' tells survival tale 11 years later

Pasquale Buzzelli, a New Jersey engineer for the Port Authority, was in the north tower of World Trade Center in New York City when it collapsed after being hit by a plane during the 9/11 terrorist attack. Despite working on the 64th floor, he survived.

Buzzelli, and his wife Louise, joined Morning Joe Tuesday, on the 11th anniversary of 9/11 terrorist, to discuss their story, which will also appear in a documentary airing on Discovery Channel at 8 p.m. tonight.

Buzzelli and some of his colleagues had remained in the building in part to keep the stairways clear for rescue personnel, but when they "felt a rumbling," they decided to gather their things and make their way down. By the time they made it into the twenties, another "loud, tremendous rumbling" shook the building. Buzzelli went to a far wall and curled up in the fetal position, trying to protect himself from falling debris. The "floor cracked and gave way," and he thought, "I'm going to die."

When he looked up, he saw blue sky. "I couldn't believe I was alive."

Buzzelli, dubbed the "9/11 Surfer," had somehow landed safely on a pile of rubble that had been the World Trade Center after about a 15-story fall.

Meanwhile, his pregnant wife was at home watching the tower collapse and thinking her husband had just died.

MSNBC's Willie Geist narrates The 9/11 Surfer Tuesday night.

- TV & Film

- Say Maaate to a Mate

- First Impressions - The Game

- Daily Ladness

- Citizen Reef

To make sure you never miss out on your favourite NEW stories , we're happy to send you some reminders

Click ' OK ' then ' Allow ' to enable notifications

9/11 survivor describes the feeling of falling 22 stories as building collapsed

Pasquale buzzelli, known as the '9/11 surfer', survived the terrorist attacks as the north tower collapsed.

Gregory Robinson

A man who survived the 9/11 attacks has his described his incredible survival story in a powerful interview.

Pasquale Buzzelli, who became known as the '9/11 surfer', arrived at work on the morning of 11 September, 2001 in the North Tower of the World Trade Center when a plane struck the building.

Buzzelli, like the rest of the world , had no idea of the horror that would unfold that fateful Tuesday, or how he would become one of the survivors.

He sat down with internet personality Joe Budden to speak about his miraculous survival story.

He worked on the 64 th floor and the first sign of trouble came when he rode the elevator up to work but felt the structure drop several feet.

Once he arrived at his desk, Buzzelli called his wife, Louise, and asked her to turn the TV on to see what was wrong. Louise was horrified when she saw reports about a plane flying into the North Tower.

With his fellow office workers, Buzzelli attempted to escape through a stairwell. By the time they reached the 22 nd floor, the building had started to rumble and shake and a 'tremendous pounding noise' he compared to the sound of a freight train.

All Buzzelli had was a briefcase as the building continued shaking. Fearing that debris was about to fall through the staircase, Buzzelli made a leap of faith.

He explained: “I look back and I dove from basically the middle of [the] stairs.

"I just took a couple of steps and I jumped and I landed on that intermittent platform landing and I just put myself right into the corner and I curled up and tried to make myself as small as possible in the corner there thinking whatever’s falling through, there was nothing to protect me other than the floor below me and the two walls that I can get into a corner on, so I just kind of curled up.

“I had nowhere to run.”

The ‘freight train’ sound was the noise of the floors from above collapsing and ‘pancaking’.

When Buzzelli felt the wall next to him ‘crack’ and the ‘floor start to give’ his thoughts turned to his wife and daughter.

“I can’t believe this is how I die,” he remembered thinking as he fell while on a slab of concrete he 'surfed' as the building collapsed.

“I’m on this sub but it broke away and I’m kind of like free falling, getting knocked around, getting hit… I see flashes of light from getting hit in the head, you know, some even say you see stars."

“I was getting knocked around in the head, my back. I just stayed tucked in. This is all happening quick. All those thoughts are going through my head and then I see one big boom. Flash,” he added.

Buzzelli lost 14 colleagues who were with him when the tower collapsed. He described feeling a sense of guilt after he made it out of the tower with a broken leg and ankle.

The horrendous terrorist attacks in New York City claimed the lives of nearly 3,000 people. The city was forever changed and life shifted drastically for those who survived.

Topics: News , US News

Gregory is a journalist for LADbible. After graduating with a master's degree in journalism, he has worked for both print and online publications and is particularly interested in TV, (pop) music and lifestyle. He loves Madonna, teen dramas from the '90s and prefers tea over coffee.

Choose your content:

Scary moment plane smashes nose into runway while having to perform emergency landing

The boeing pilot tried to perform an emergency landing after finding out that his landing gear had failed.

The nine personality traits someone must show in order to be diagnosed as a narcissist

You need to show just five of the nine traits to be diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder.

Little-known sunglasses rule could catch British drivers out this summer

Although your shades might look the business, they might not be legal to drive in.

New images show incredible development of Saudi Arabia's £800 billion project 'The Line'

The project could costing more than twice as much as planned.

- Newly Restored Footage Shows The Horrific Aftermath Of 9/11 Attacks

- Tragic Story Of FBI Agent Who Warned About Growing Threat Of US Terrorist Attack Prior To 9/11

- American Man Who Survived 9/11 Killed In Terror Attack In Nairobi

- Never Before Seen Footage From 9/11 Has Just Appeared Online

- Tout le programme TV

- Toutes les chaines

- Câble - Adsl - Satellite

- Films à la TV

- Le guide Netflix

- Le guide Prime Video

- Le guide des chaînes Canal+

- Toutes les news

- Tous les événements

- Mon petit renne (Netflix)

- The Voice 2024

- Secret Story 2024

- Fiasco (Netflix)

- Terminal (Canal+)

- Koh-Lanta, les chasseurs d'immunité

- Pékin Express, saison 18

- Mask Singer 2024

- Toutes les séries

- Top 50 Séries

- Séries à la télé

- La Casa de papel

- Stranger Things

- Plus belle la vie

- Grey's Anatomy

- Demain nous appartient

- Tout le cinéma

- Sorties cinéma

- Prochainement

- Tous les films

- Toutes les vidéos

- Tous les podcasts

- À la demande

- Previously : Les séries cultes

- Yakoi en audiodescription

- Parents d'abord

- Les séries en questions

- Femmes de Télé

- Tout le sport

- Toutes les stars

- Top 100 Stars

- Programme TV

Le miraculé du 11-Septembre

- 0 Commenter

- Enregistrer

- Culture Infos Histoire

- Durée : 52min

- Sortie : 2012

- Pays : Etats-Unis

Résumé Le miraculé du 11-Septembre

Connexion à Prisma Connect

Sarasota Sailing Squadron

In 2007, the Stiletto Nationals was reformatted to be open to all multihull sailboats and renamed after the late Bob Buzzelli, an avid multihull and Stiletto sailor. The regatta has grown from a small fleet of Stilettos to a varied fleet on multiple courses.

Buzzelli Multihull Rendezvous

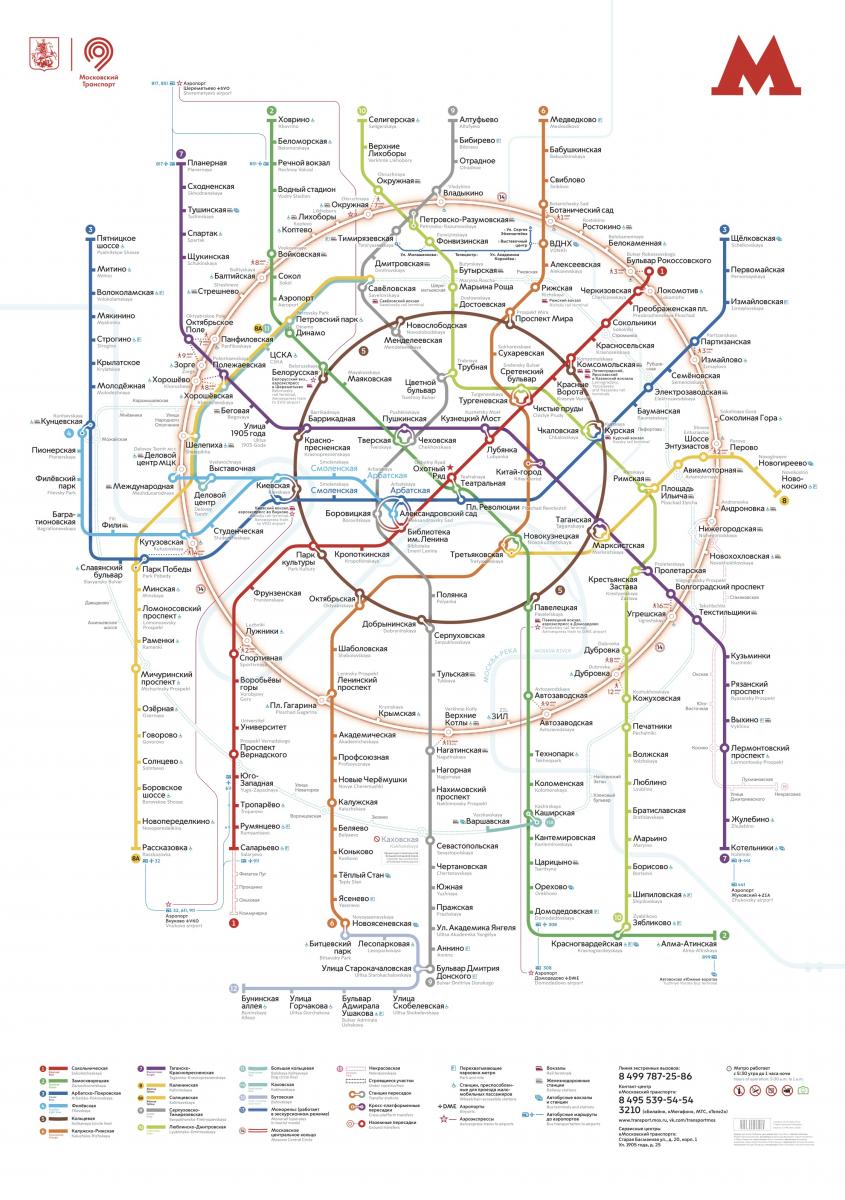

Moscow Metro Tour

- Page active

Description

Moscow metro private tours.

- 2-hour tour $87: 10 Must-See Moscow Metro stations with hotel pick-up and drop-off

- 3-hour tour $137: 20 Must-See Moscow Metro stations with Russian lunch in beautifully-decorated Metro Diner + hotel pick-up and drop off.

- Metro pass is included in the price of both tours.

Highlight of Metro Tour

- Visit 10 must-see stations of Moscow metro on 2-hr tour and 20 Metro stations on 3-hr tour, including grand Komsomolskaya station with its distinctive Baroque décor, aristocratic Mayakovskaya station with Soviet mosaics, legendary Revolution Square station with 72 bronze sculptures and more!

- Explore Museum of Moscow Metro and learn a ton of technical and historical facts;

- Listen to the secrets about the Metro-2, a secret line supposedly used by the government and KGB;

- Experience a selection of most striking features of Moscow Metro hidden from most tourists and even locals;

- Discover the underground treasure of Russian Soviet past – from mosaics to bronzes, paintings, marble arches, stained glass and even paleontological elements;

- Learn fun stories and myths about Coffee Ring, Zodiac signs of Moscow Metro and more;

- Admire Soviet-era architecture of pre- and post- World War II perious;

- Enjoy panoramic views of Sparrow Hills from Luzhniki Metro Bridge – MetroMost, the only station of Moscow Metro located over water and the highest station above ground level;

- If lucky, catch a unique «Aquarelle Train» – a wheeled picture gallery, brightly painted with images of peony, chrysanthemums, daisies, sunflowers and each car unit is unique;

- Become an expert at navigating the legendary Moscow Metro system;

- Have fun time with a very friendly local;

- + Atmospheric Metro lunch in Moscow’s the only Metro Diner (included in a 3-hr tour)

Hotel Pick-up

Metro stations:.

Komsomolskaya

Novoslobodskaya

Prospekt Mira

Belorusskaya

Mayakovskaya

Novokuznetskaya

Revolution Square

Sparrow Hills

+ for 3-hour tour

Victory Park

Slavic Boulevard

Vystavochnaya

Dostoevskaya

Elektrozavodskaya

Partizanskaya

Museum of Moscow Metro

- Drop-off at your hotel, Novodevichy Convent, Sparrow Hills or any place you wish

- + Russian lunch in Metro Diner with artistic metro-style interior for 3-hour tour

Fun facts from our Moscow Metro Tours:

From the very first days of its existence, the Moscow Metro was the object of civil defense, used as a bomb shelter, and designed as a defense for a possible attack on the Soviet Union.

At a depth of 50 to 120 meters lies the second, the coded system of Metro-2 of Moscow subway, which is equipped with everything you need, from food storage to the nuclear button.

According to some sources, the total length of Metro-2 reaches over 150 kilometers.

The Museum was opened on Sportivnaya metro station on November 6, 1967. It features the most interesting models of trains and stations.

Coffee Ring

The first scheme of Moscow Metro looked like a bunch of separate lines. Listen to a myth about Joseph Stalin and the main brown line of Moscow Metro.

Zodiac Metro

According to some astrologers, each of the 12 stops of the Moscow Ring Line corresponds to a particular sign of the zodiac and divides the city into astrological sector.

Astrologers believe that being in a particular zadiac sector of Moscow for a long time, you attract certain energy and events into your life.

Paleontological finds

Red marble walls of some of the Metro stations hide in themselves petrified inhabitants of ancient seas. Try and find some!

- Every day each car in Moscow metro passes more than 600 km, which is the distance from Moscow to St. Petersburg.

- Moscow subway system is the 5th in the intensity of use (after the subways of Beijing, Tokyo, Seoul and Shanghai).

- The interval in the movement of trains in rush hour is 90 seconds .

What you get:

- + A friend in Moscow.

- + Private & customized Moscow tour.

- + An exciting pastime, not just boring history lessons.

- + An authentic experience of local life.

- + Flexibility during the walking tour: changes can be made at any time to suit individual preferences.

- + Amazing deals for breakfast, lunch, and dinner in the very best cafes & restaurants. Discounts on weekdays (Mon-Fri).

- + A photo session amongst spectacular Moscow scenery that can be treasured for a lifetime.

- + Good value for souvenirs, taxis, and hotels.

- + Expert advice on what to do, where to go, and how to make the most of your time in Moscow.

Write your review

- Preplanned tours

- Daytrips out of Moscow

- Themed tours

- Customized tours

- St. Petersburg

Moscow Metro 2019

Will it be easy to find my way in the Moscow Metro? It is a question many visitors ask themselves before hitting the streets of the Russian capital. As metro is the main means of transport in Moscow – fast, reliable and safe – having some skills in using it will help make your visit more successful and smooth. On top of this, it is the most beautiful metro in the world !

. There are over 220 stations and 15 lines in the Moscow Metro. It is open from 6 am to 1 am. Trains come very frequently: during the rush hour you won't wait for more than 90 seconds! Distances between stations are quite long – 1,5 to 2 or even 3 kilometers. Metro runs inside the city borders only. To get to the airport you will need to take an onground train - Aeroexpress.

RATES AND TICKETS

Paper ticket A fee is fixed and does not depend on how far you go. There are tickets for a number of trips: 1, 2 or 60 trips; or for a number of days: 1, 3 days or a month. Your trips are recorded on a paper ticket. Ifyou buy a ticket for several trips you can share it with your traveling partner passing it from one to the other at the turnstile.

On every station there is cashier and machines (you can switch it to English). Cards and cash are accepted. 1 trip - 55 RUB 2 trips - 110 RUB

Tickets for 60 trips and day passes are available only at the cashier's.

60 rides - 1900 RUB

1 day - 230 RUB 3 days - 438 RUB 30 days - 2170 RUB.

The cheapest way to travel is buying Troyka card . It is a plastic card you can top up for any amount at the machine or at the ticket office. With it every trip costs 38 RUB in the metro and 21 RUB in a bus. You can get the card in any ticket office. Be prepared to leave a deposit of 50 RUB. You can get it back returning the card to the cashier.

SamsungPay, ApplePay and PayPass cards.

One turnstile at every station accept PayPass and payments with phones. It has a sticker with the logos and located next to the security's cabin.

GETTING ORIENTED

At the platfrom you will see one of these signs.

It indicates the line you are at now (line 6), shows the direction train run and the final stations. Numbers below there are of those lines you can change from this line.

In trains, stations are announced in Russian and English. In newer trains there are also visual indication of there you are on the line.

To change lines look for these signs. This one shows the way to line 2.

There are also signs on the platfrom. They will help you to havigate yourself. (To the lines 3 and 5 in this case).

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Un survivant du 11 septembre raconte ce qu'il a vécu lors de l'effondrement d'une des tours jumelles Dans une interview bouleversante, un homme qui a survécu aux attentats du 11 septembre 2001 revient sur son incroyable histoire et décrit sa chute de 22 étages suite à l'effondrement d'une des tours jumelles.

Découvrez l'histoire incroyable de Pasquale Buzzelli, un Américain, qui le 11 septembre 2001, s'est retrouvé piégé dans la tour Nord du World Trade Center au...

Le miraculé du 11 Septembre. Au 22ème étage d'une des deux tours jumelles, Pasquale Buzzelli a survécu à une veritable tempête de débris. Evitant un nombre invraisemblable d'obstacles guidé par son instinct de survie, ce miraculé nous raconte en détail son expérience. Cette histoire inédite donne un nouveau souffle à l'un des jours ...

Buzzelli's office had been on the 64th floor of the North Tower. At about 10 a.m. on September 11, 2001, he'd phoned his wife for the second time that morning. "Don't worry," he said.

The True Stroy of the 9/11 Surfer The story of a miracle... WE ALL FALL DOWN: THE TRUE STORY OF THE 9/11 SURFER is authored by 9/11 survivor Pasquale Buzzelli and his wife Louise, co-written by Joseph Bittick, and edited by Autumn Conley. The memoir/biographical work tells the story of the "9/11 Surfer," survivor of the collapse of the WTC North Tower, and his wife Louise Buzzelli, detailing ...

Pasquale Buzzelli was rescued from the twin towers on 9/11, and 10 years later still feels lucky to be able to come home and see his daughter. Andrew Siff reports. Thousands of people went into ...

Le Seven World Trade Center, édifice de 47 étages situé à un jet de pierre des tours jumelles, s'effondre à son tour, des heures après avoir été évacué. ... Pasquale Buzzelli ...

Despite working on the 64th floor, he survived. Buzzelli, and his wife Louise, joined Morning Joe Tuesday, on the 11th anniversary of 9/11 terrorist, to discuss their story, which will also appear ...

Retrouvez les intégrales de l'émission sur FranceTV : https://www.france.tv/france-2/ca-commence-aujourd-hui/ Le 11 septembre 2001, 2 avions percutaient les ...

Pasquale Buzzelli, who became known as the '9/11 surfer', arrived at work on the morning of 11 September, 2001 in the North Tower of the World Trade Center when a plane struck the building. Advert ...

Abonnez-vous http://bit.ly/inasociete12/14 | France 3 | 12 septembre 2001Des attentats terroristes ont frappé les tours jumelles du World Trade Center à Ne...

Pasquale Buzzelli, qui se trouvait au 22e étage d'une des deux tours jumelles du World Trade Center lors des attentats du 11-Septembre, est un miraculé. Après avoir survécu à une véritable ...

Sarasota Sailing Squadron. In 2007, the Stiletto Nationals was reformatted to be open to all multihull sailboats and renamed after the late Bob Buzzelli, an avid multihull and Stiletto sailor. The regatta has grown from a small fleet of Stilettos to a varied fleet on multiple courses.

Days. 00. Hours. 00. Minutes

11 septembre 2001 : quatre avions remplis de passagers s'écrasent en plein cœur de New-York sur les tours jumelles qui s'effondrent et sur le Pentagone. Au t...

Moscow Metro. The Moscow Metro Tour is included in most guided tours' itineraries. Opened in 1935, under Stalin's regime, the metro was not only meant to solve transport problems, but also was hailed as "a people's palace". Every station you will see during your Moscow metro tour looks like a palace room. There are bright paintings ...

2-hour tour $87: 10 Must-See Moscow Metro stations with hotel pick-up and drop-off. 3-hour tour $137: 20 Must-See Moscow Metro stations with Russian lunch in beautifully-decorated Metro Diner + hotel pick-up and drop off. Metro pass is included in the price of both tours.

Customized tours; St. Petersburg; SMS: +7 (906) 077-08-68 [email protected]. Moscow Metro 2019. Will it be easy to find my way in the Moscow Metro? It is a question many visitors ask themselves before hitting the streets of the Russian capital. As metro is the main means of transport in Moscow - fast, reliable and safe - having some ...

Le matin du 11 septembre 2001, deux Boeing 767 percutaient les Tours Jumelles du World Trade Center (WTC). Moins de deux heures plus tard, les deux Tours s'...

Moscow has some of the most well-decorated metro stations in the world but visitors don't always know which are the best to see. This guided tour takes you to the city's most opulent stations, decorated in styles ranging from neoclassicism to art deco and featuring chandeliers and frescoes, and also provides a history of (and guidance on how to use) the Moscow metro system.