Advertisement

How the Digestive System Works

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

There are very few things in this world that you can honestly say you can't live without. Your digestive system is definitely one of those things. Simply put, this system is in charge of absorbing and transporting all the nutrients your body needs in order to thrive -- and it gets rid of all the waste the body doesn't need. As you read this article, your digestive system is chugging along, all its parts working together as a team (well, at least we hope it is).

This digestive team is composed of a bunch of hollow passageways that start at your mouth and end at your anus. These organs are aided by a couple of friends, the liver and the pancreas, with a few cameos from the brain and nerves .

Everything you eat takes a long journey through your body -- if stretched out, the system would measure about 30 feet, most of it the winding intestines [source: Kids Health: Digestive System ]. And the entire ride is usually over in a matter of hours. Of course, there can be bumps in the digestive road, but we'll get to those later.

So how exactly do all of these organs work together? Let's begin by following the topsy-turvy journey of a ham and cheese sandwich.

The Digestive Tract: Mouth to the Stomach

The large and small intestines, digestive accessories: organs and glands, digestion process, absorption and transport of nutrients, digestive problems at the top, digestive disorders at the bottom.

Let's say you've picked up a ham and cheese sandwich for lunch. Before you even take a bite, your nose smells it and signals the brain , which sends word to the nerves controlling your mouth's salivary (spit) glands. Once the glands have their cue, they get busy secreting juices, making your mouth water. When you bite into the sandwich, the salivary glands get even more excited and secrete more saliva, making the food moister and easier to swallow.

Before the sandwich even leaves your mouth, an enzyme in your saliva called amylase begins to break down the carbohydrates in the bread. When you swallow, the sandwich pieces slide down your pharynx , also known as the throat. They then come to a fork in the road: One pathway is the esophagus , which leads to the stomach, and the other follows the trachea , which leads to the lungs . Of course, the correct path is through the esophagus, but sometimes food can take a careless detour. So when we say something went down the "wrong pipe," it means it went through the trachea, usually because you were breathing or laughing when you swallowed. Not to worry, this rarely happens -- the act of swallowing closes the epiglottis , a flexible flap over the trachea. So the sandwich pieces will normally slide into the esophagus through the upper esophageal sphincter , a ring-shaped muscle that opens only when food is swallowed.

Once the sandwich is in the esophagus, involuntary muscle contractions -- or peristalses -- push it toward the stomach. At the end of the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter lets the food into the stomach. It opens and then quickly closes to keep the food from escaping back into the esophagus. Ever had heartburn? This occurs when this sphincter isn't working properly and stomach acid manages to splash into the esophagus. If this happens chronically, you might have Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease , or GERD.

In the stomach, the food begins its preparation for the small intestine . Glands in the stomach secrete acid, enzymes and a mucous that coats and protects the stomach from its own acids and prevents ulcers. The stomach's smooth muscles contract about every 20 seconds, stirring up the acid and enzymes and turning your sandwich into a liquefied blob ( chyme ). But some foods just can't be reduced to chyme and remain a pasty, solid substance that is released into the small intestine in a process that takes more than an hour. Your liquefied sandwich, however, can be out of the stomach in a mere 20 minutes [source: Gastro.net ].

Next stop: the small intestine.

Your now unidentifiable sandwich squirts into the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine. The breakdown process continues with enzymes from the pancreas and bile from the liver. Again, peristalsis helps mix up these juices. The next small intestine section is the coiled jejunum, followed by the ileum, which leads straight to the large intestine. These two sections absorb nutrients and water more than they break down food.

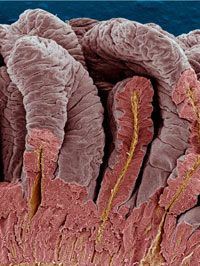

The small intestine has a smaller circumference than the large intestine, but it's actually the longer of the two sections -- it has the surface area of a tennis court! You may wonder how all this fits into your body. The answer is simple: The surface of the small intestine has many tight folds that can absorb nutrients and water -- they greatly increase the surface area. These folds are covered with villi, or tiny projections that have even smaller microvilli on them. Villi and microvilli have affinities for specific nutrients. That means that several different kinds of villi will grab the nutrients, electrolytes and dietary molecules in your sandwich (like the carbohydrates and folic acid from the bread, protein and sodium from the ham, and calcium and vitamin B12 from the cheese ). The absorbed nutrients move through the wall of the intestines and into blood vessels that take them throughout the body.

Once all the good stuff is taken from the food, the indigestible parts are transported into the large intestine, the final stretch of the digestive process. The large intestine absorbs extra fluid to produce the solid waste we know as feces. To move the waste, the colon uses the same involuntary muscular movements that we learned about earlier. Unlike the stomach and small intestines, though, whose movements take a matter of hours, it takes days for waste to move through the large intestine -- the waste moves at a pace of about 1 centimeter per hour [source: Gastro.net ].

The large intestine has three main parts. First is a pouch called the cecum. (The cecum is home to the appendix, the small fingerlike pouch that can become inflamed and extremely painful in some people.) Next comes the colon, which has three sections: ascending, transverse and descending. In the first two sections, salts and fluids are absorbed from the indigestible food. Billions of bacteria that normally live in the colon help to ferment and absorb substances like fiber. While these tracts absorb, they also produce mucus that helps feces move easily through the descending colon and into the third part of the large intestine: the rectum. Here, your feces wait to be excreted through the anus in your next bowel movement.

While your sandwich moves through the system, other organs, glands, hormones and nerves are pitching in as well. We'll find out what they do and why you should care.

- The largest tapeworms can grow up to 30 feet long [source: New York Times ].

The stomach and intestines get a lot of help from other organs, glands, hormones and a few nerves. Let's look at what these digestive accessories do and how they've made themselves essential to the process.

The main organ involved in digestion is the largest in the body, the liver , which accounts for about 2.5 percent of your overall body weight [source: Gastro.net ]. The liver has a big impact on your bodily functions. In terms of digestion, it is involved in breaking up, digesting and absorbing fats . This is all thanks to bile , a brownish-yellowish fluid that's made in the liver and excreted through the bile ducts and into the small intestine.

The liver's extra bile is stored in the gallbladder . When food starts heading to the intestines, they signal the gallbladder to give up the bile. If the gallbladder has to be removed for one reason or another, the liver just stores the extra bile in newly expanded bile ducts.

The pancreas may be smaller than the liver, but it's an efficient factory. It produces pancreatic juices, which are made up of enzymes that help in digestion. An enzyme is a protein that can cause chemical changes in organic substances like food. The enzymes in the pancreas cause chemical changes that, with the help of bile, break down proteins, fats and carbohydrates.

Essential glands are all over the digestive system, from the mouth to the intestines. In the mouth, salivary glands are there to start the process. Saliva moistens your food and uses an enzyme to begin breaking down starch into smaller molecules.

The stomach glands excrete juices that are a little stronger. When the food arrives, glands in the stomach lining squirt out acids that break down food. They also produce an enzyme specifically designed to break down proteins, like in meat. This breakdown continues when the food encounters even more glands in the intestinal walls. These are in charge of excreting enzymes that work with bile and the pancreatic juices to keep breaking down food and absorbing its nutrients.

Our digestive system might seem a little odd at first, but we have nothing on cows . This system basically has more of everything from stomach compartments to bacteria. Things are weird from the start -- a cow chews and re-chews, up to 60,000 times a day. Once food has slipped down the esophagus, it lands in the first of four stomach compartments, the reticulum. This section allows the cow to regurgitate its food for even more chewing. Next, the well-chewed food moves to the rumen. Bacteria and protozoa aid the digestive process -- in this compartment alone there are half a million bacteria and 50 billion protozoa.

Next, the food slides right into the third compartment, the omasum. Here any of the volatile fatty acids that weren't absorbed in the second compartment get absorbed along with liquids like water and potassium. All this absorbing dries out the remaining food products, which are now ready for the last compartment, the abomasums. This is often called the "true" stomach because it works much like your stomach. The rest of the digestive system is no surprise -- small intestines, large intestines and rectum. All of these stomach compartments give cows a hugely productive digestive system. In 10 months, a cow can ingest enough protein for you to thrive for 10 years, enough energy for five years, and enough calcium for 30 years [source: General Anatomy of the Ruminant Digestive System ].

Hormones control the regulation of the entire digestive process -- some even regulate your appetite. The hormones produced in the mucosa cells of the stomach and small intestines work by stimulating these organs and their digestive juices.

The three hormones responsible for the digestion of your sandwich are gastrin, secretin and cholecystokinin (CCK).

- Gastrin gives the stomach the signal to produce acid. It also plays an important role in the growth of the stomach, small intestine and colon lining -- which, as you now know, is needed for absorbing nutrients and excreting digestive juices.

- Secretin communicates with all the major digestive accessory organs. In the pancreas, a call from secretin causes the excretion of those helpful digestive juices. Then secretin calls the stomach, causing it to produce pepsin , an enzyme used to digest protein. Secretin's final call is the liver, which then produces more of that much-needed bile.

- CCK talks to the little organs: the pancreas and the gallbladder. With the help of this hormone the pancreas grows and produces more enzymes. Once the gallbladder hears from CCK, it knows to release all the bile it has been storing for the liver.

As we mentioned, a few hormones also work to encourage you to start and stop eating that food . The first of these is ghrelin , which both the stomach and small intestine produce when there is no food in them. So, when ghrelin levels run high, your appetite is stimulated. Peptide YY , a hormone made in the gastrointestinal tract, works in an opposite manner. Once you finish that sandwich, it's excreted to quell your hunger .

Not surprisingly, nerves are involved in digestion regulation.

- Extrinsic nerves are based in the unconscious part of the brain and in the spinal cord, and they need the help of the chemicals acetylcholine and adrenaline . Acetylcholine works with hormones to encourage the stomach and pancreas to make more digestive juices. But its main function involves the movement of the digestive organs. Once released by an extrinsic nerve, acetylcholine causes these organs' muscles to contract and move food through that long digestive tract. Adrenaline, on the other hand, relaxes these muscles when no food is in the system.

- Intrinsic nerves are embedded all along the digestive tract, from the esophagus to the colon. These nerves don't get their signal from the brain but instead jump into action when your food stretches the walls of the various hollow digestive organs. Depending on the amount of stretching, these nerves release an abundant amount of substances that can either speed up or slow down the digestive process.

The most common type of gastric bypass surgery is the Roux-en-Y procedure, in which the small intestine is rearranged into a Y-shaped configuration. One part of this Y, referred to as a "Roux limb," works to move food from the new, smaller stomach pouch into the small intestine, which then bypasses the lower stomach, the duodenum and the first portion of the jejunum to reduce absorption.

The procedure has relatively few complications, but one important one is malabsorption. Because the small intestine is now shorter, the patient absorbs fewer calories -- but also fewer nutrients. This can often result in a lack of iron, calcium or B12 in the body, leading to anemia and even osteoporosis. To learn more, read How Gastric Bypass Surgery Works.

Nearly 140,000 Americans had gastric bypass surgery in 2005 [source: American Society for Bariatric Surgery]. This surgery works by altering the digestive process with two steps. First, the stomach, which is usually the size of a football, is reduced to the size of an egg. Then the small intestine is rerouted so food bypasses parts of it. As a result, the patient feels fuller faster and absorbs fewer calories. This can result in a slow, yet dramatic, weight loss over a matter of months

Now that you have the road map to your digestive system, along with the lowdown on its accessories, let's see how everything works together to give your body all the nutrients you need.

- Carbohydrates: Remember that ham and cheese sandwich we followed earlier? The bread is made up largely of carbohydrates, which begin to break down when you take that first bite. They continue to be broken down by the digestive juices in the pancreas and small intestine lining and are then absorbed in the small intestines, where they enter the bloodstream. The starch in the bread is broken down in much the same way, but with an extra step. Its breakdown produces glucose , which is stored in the liver and provides you with energy .

- Protein: The ham consists of protein molecules that need to be digested -- protein is the key player in building and repairing your body tissues. Enzymes first attack these molecules in the stomach, and they're finished off in the small intestine with help from enzymes and those handy pancreatic and intestinal lining juices. Then the smaller protein molecules become known as amino acids . They're now small enough to be absorbed through the small intestine and right into the blood.

- Vitamins: While our food is digested, vitamins are absorbed in the small intestine. There are two basic types of vitamins in the food we eat: water-soluble and fat-soluble . The water-soluble vitamins (B vitamins and vitamin C) are absorbed easily along with the water in the small intestine, where they then travel through the body via the blood vessels. Fat-soluble vitamins (vitamins A, D, and K) are absorbed just like the fat mentioned above. Once absorbed, however, they are stored for long periods of time in cells called lipocytes . Water-soluble vitamins don't stay in your body for long -- extra amounts of these are usually eliminated in a quick trip to the bathroom.

Ever wonder how long it takes for your food to become your poop? We have the answers to a few of your favorites.

- Banana: four hours

- Bowl of cereal: four hours

- Hot dog: seven hours

- Red meat: 12 hours

- Gum : Never. Gum doesn't get digested -- it just eventually passes right through you.

[sources: Unani, Unasked.com, MadSci Network ]

With all the steps involved, there are bound to be some bumps in the digestive road. Many of the following digestive problems may seem relatively harmless, but approximately 14 million people end up hospitalized each year because of them [source: National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse ]. The full list is probably too long to keep most people's attention, so we'll discuss a few of the most common -- starting from the top.

- Belching: Some people are better at it than others, but all burping is the result of the same factor: air. If you drink bubbly beverages or swallow air when eating, air collects in the stomach and then gets pushed back out your esophagus and quickly out the mouth. Three to four burps after a meal is considered normal -- more than that and you might have a medical condition, like an ulcer.

- Vomiting: Vomiting is the forceful expulsion of stomach contents up through the esophagus, usually propelled by the abdominal muscles. One of the most common reasons for vomiting is foreign bacteria that have hitched a ride on your food. Once those bacteria irritate the gastrointestinal system, a signal is sent to the brain and vomiting soon commences. Viral stomach infections are no better -- they can cause vomiting for days until the virus is out of the body. Another digestive reason for vomiting is a food allergy , like lactose intolerance. If the food itself isn't the problem, you might want to watch the overeating, another common cause of vomiting.

- Gastroesophageal Reflux Disorder (GERD): Symptoms of this chronic digestive disorder are seen in nearly 22 million Americans and cause more than 700,000 hospitalizations each year. People who suffer from GERD essentially have a lazy esophageal sphincter, that valve connecting the stomach and the esophagus. The lazy sphincter allows acidic stomach contents to come back up into the esophagus. The presence of all this acid in the esophagus results in a burning sensation in the middle of the chest, better known as heartburn [source: National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse ].

- Peptic Ulcers: A peptic ulcer is essentially a hole in the lining of the stomach or the first part of the small intestine. Once thought to be a reaction to stress, it is now known to be caused by an invasion of the Helicobacter pylori bacterium or of certain medications, like anti-inflammatory drugs. These culprits manage to weaken the protective mucous in the stomach and allow acid to eat through.

- Stomach Bug: It's no accident that an illness that involves cramps, abdominal pain, diarrhea and vomiting is referred to as a "bug." That's because most gastrointestinal infections are caused by unwanted bacteria, viruses and parasites. The names of these little germs depend on where you live, but the most common offenders in the United States include salmonella, shigella, E. coli bacteria and the parasite giardia.

- Lactose Intolerance: Lactose intolerance, which affects up to 50 million Americans, is the inability to digest the major sugar in milk [source: National Digestive Disease Information Clearinghouse ]. If you're lactose intolerant, your digestive system doesn't produce enough of the enzyme lactase , which is found in the small intestine. So, it doesn't break down milk into simpler sugars that the body can digest. Those with lactose intolerance experience mild to severe nausea, cramps, bloating, gas or diarrhea, usually 30 minutes to two hours after ingesting a dairy product.

We've covered the throat, the stomach, and even a tiny bit of the small intestines. But plenty of problems occur below the stomach, too. We'll discuss the most common digestive problems below the belt in the next section.

Let's explore the problems that you might encounter after your food passes through your stomach and enters the intestines. These winding organs can be home to many an ailment, but again, we'll stick to the most common disorders.

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD): There are two major types of IBD, a chronic inflammation of the intestines: ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease . These sometimes debilitating conditions affect more than 600,000 Americans every year [sources: Family Doctor , National Digestive Disease Information Clearinghouse ]. Both diseases create ulcers in the intestines, which results in abdominal cramps, diarrhea, intestinal bleeding and weight loss. Crohn's disease generally affects the entire small and large intestines, and ulcerative colitis usually occurs only in the large intestine, beginning at the rectum.

- Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): Unlike IBD, which is a structural problem in the intestines, IBS is a functional problem. There's no visible damage, like ulcers or tumors, but the intestines are causing trouble. People with IBS can have recurring, unexpected bouts of abdominal pain, bloating, constipation and diarrhea. Many times these symptoms are triggered by ordinary things like stress, hormonal changes and even antibiotics . The exact cause isn't known, but a leading theory is a problem with the signals between the brain and the intestines.

- Celiac Disease: Here, your immune system is to blame -- it damages the digestive system when you eat gluten , a protein found in wheat, rye, barley and the many foods made with these products. People with celiac disease can't easily digest nutrients from gluten-filled foods and experience diarrhea, abdominal bloating and exhaustion. But they can avoid problems if they keep their diets gluten-free.

- Tapeworms: Tapeworms aren't as common as other digestive ailments, but they're worth mentioning for the gross-out factor. Tapeworm eggs or larvae enter your digestive tract via contaminated food. Once they've settled into your intestines, they begin stealing nutrients, like vitamin B12. Strangely, most people won't experience any symptoms. But if the freeloading goes on long enough, you can suffer from malnutrition, weakness, nausea, abdominal pain, diarrhea and weight loss. The ultimate danger comes when the worms decide to move into other parts of your body, like your lungs or liver. There, they form cysts that can cause much more serious problems.

- Flatulence: We all know that everybody farts, but do you know why we do it and how much? Gasses like hydrogen, carbon dioxide and methane are produced during food breakdown in the large intestine. When excess gas is sensed in the rectum, a signal is sent to the brain, which ascertains if it's a good time to release the gas. If it's a go, the sphincters relax, the rectum contracts and a fart is born. An average person produces up to 3 pints of gas per day and will pass it 10 to 25 times a day. If it's happening more often, you might have a digestive issue, like lactose intolerance [source: WebMD: Flatulence ].

- Constipation: An introduction might not be necessary, but constipation is defined as difficult, infrequent or incomplete bowel movements. The meaning of "infrequent" can vary -- anything between three times a day to three times a week is considered normal [source: WebMD ]. The bottom line is: If your stools pass without discomfort and are a normal consistency, you're not constipated. This uncomfortable condition is caused a slow-moving large intestine. When stool stays there for too long, too much water is removed, making it hard. While occasional constipation isn't a problem, chronic constipation can lead to painful hemorrhoids or fissures.

- Diarrhea: Diarrhea happens when muscle contractions cause a person's intestines to move too fast, and the intestines don't have time to absorb water from the waste matter before it's sent out of the body. Intestinal inflammation can also create diarrhea by leaking fluid into the stool. There are numerous causes of diarrhea, from bacteria to stress, so it's no wonder that most Americans suffer around four bouts of it every year [source: WebMD ].

To learn more about digestion, take a gander at the links on the next page.

Lots More Information

Related howstuffworks articles.

- The Ultimate Human Body Quiz

- How does your stomach keep from digesting itself?

- Why does my stomach growl?

- How long can you go without food and water?

- If I couldn't get rid of gas in any way, would I explode?

- Constipation Dictionary

- How Gastric Bypass Surgery Works

More Great Links

- Discovery Kids: Your Gross and Cool Body

- National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- WebMD: Digestive Diseases

- Auerbach: Wilderness Medicine, 4th ed. Mosby, Inc. 2001. http://www.mdconsult.com/das/book/body/89997564-3/683509740/ 1483/489.html#4-u1.0-B978-0-323-03228-5..50058-6--cesec104_2969

- American Society for Bariatric Surgery. http://www.asbs.org/html/patients/bypass.html

- Centers for Disease Control: Taeniasis. http://www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/Taeniasis.htm

- Cleveland Clinic: Gastrointestinal Disorders. http://www.clevelandclinic.org/ health/health-info/docs/1700/1700.asp?index=7040

- Cohen & Powderly: Infectious Diseases, 2nd ed., Mosby, An Imprint of Elsevier. 2004. http://www.mdconsult.com/das/book/body/89997564- 3/683509740/1209/487.html#4-u1.0-B0-323-02407-6..50170-7-- cesec14_4848

- Discovery Health Gross&Cool Body: Poo. http://yucky.discovery.com/flash/body/yuckystuff/poop/js.index.html#

- Emedicine: Tapeworm Infestation. http://www.emedicine.com/emerg/topic567.htm

- Fact or Fiction? Chewing Gum Takes Seven Years to Digest. http://www.sciam.com/article.cfm?id=8FA2DE22-E7F2-99DF-3F1DEE397 3ED24E7&page=1

- Family Doctor. http://familydoctor.org/online/famdocen/home/common/ digestive/disorders/252.html

- Gastro.net. http://www.gastro.net.au/digesitve_description.html

- General Anatomy of the Ruminant Digestive System. http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/DS061

- Heritage, Ford; Composition and Facts About Foods. Soc. of Metaphysicians (1987)

- Kids Health: Digestive System. http://kidshealth.org/parent/general/body_basics/digestive.html

- MadScientist.org: Digesting a Hot Dog. http://www.madsci.org/

- Mayo Clinic: Tapeworm Infection. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/tapeworm/DS00659/DSECTION=1

- Medtronic: GERD. http://wwwp.medtronic.com/Newsroom/LinkedItemDetails .do?itemId=1101835641931&itemType=fact_sheet

Please copy/paste the following text to properly cite this HowStuffWorks.com article:

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Entire Site

- Research & Funding

- Health Information

- About NIDDK

- Digestive Diseases

- Your Digestive System & How it Works

- Español

Your Digestive System & How it Works

On this page:

What is the digestive system?

Why is digestion important, how does my digestive system work, how does food move through my gi tract, how does my digestive system break food into small parts my body can use, what happens to the digested food, how does my body control the digestive process, clinical trials.

The digestive system is made up of the gastrointestinal tract—also called the GI tract or digestive tract—and the liver , pancreas , and gallbladder. The GI tract is a series of hollow organs joined in a long, twisting tube from the mouth to the anus . The hollow organs that make up the GI tract are the mouth, esophagus , stomach, small intestine, large intestine, and anus. The liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are the solid organs of the digestive system.

The small intestine has three parts. The first part is called the duodenum. The jejunum is in the middle and the ileum is at the end. The large intestine includes the appendix , cecum, colon , and rectum. The appendix is a finger-shaped pouch attached to the cecum. The cecum is the first part of the large intestine. The colon is next. The rectum is the end of the large intestine.

Bacteria in your GI tract, also called gut flora or microbiome, help with digestion . Parts of your nervous and circulatory systems also help. Working together, nerves, hormones , bacteria, blood, and the organs of your digestive system digest the foods and liquids you eat or drink each day.

Digestion is important because your body needs nutrients from food and drink to work properly and stay healthy. Proteins , fats , carbohydrates , vitamins , minerals , and water are nutrients. Your digestive system breaks nutrients into parts small enough for your body to absorb and use for energy, growth, and cell repair.

- Proteins break into amino acids

- Fats break into fatty acids and glycerol

- Carbohydrates break into simple sugars

MyPlate offers ideas and tips to help you meet your individual health needs .

Each part of your digestive system helps to move food and liquid through your GI tract, break food and liquid into smaller parts, or both. Once foods are broken into small enough parts, your body can absorb and move the nutrients to where they are needed. Your large intestine absorbs water, and the waste products of digestion become stool . Nerves and hormones help control the digestive process.

The digestive process

Food moves through your GI tract by a process called peristalsis. The large, hollow organs of your GI tract contain a layer of muscle that enables their walls to move. The movement pushes food and liquid through your GI tract and mixes the contents within each organ. The muscle behind the food contracts and squeezes the food forward, while the muscle in front of the food relaxes to allow the food to move.

Mouth. Food starts to move through your GI tract when you eat. When you swallow, your tongue pushes the food into your throat. A small flap of tissue, called the epiglottis, folds over your windpipe to prevent choking and the food passes into your esophagus.

Esophagus. Once you begin swallowing, the process becomes automatic. Your brain signals the muscles of the esophagus and peristalsis begins.

Lower esophageal sphincter. When food reaches the end of your esophagus, a ringlike muscle—called the lower esophageal sphincter —relaxes and lets food pass into your stomach. This sphincter usually stays closed to keep what’s in your stomach from flowing back into your esophagus.

Stomach. After food enters your stomach, the stomach muscles mix the food and liquid with digestive juices . The stomach slowly empties its contents, called chyme , into your small intestine.

Small intestine. The muscles of the small intestine mix food with digestive juices from the pancreas, liver, and intestine, and push the mixture forward for further digestion. The walls of the small intestine absorb water and the digested nutrients into your bloodstream. As peristalsis continues, the waste products of the digestive process move into the large intestine.

Large intestine. Waste products from the digestive process include undigested parts of food, fluid, and older cells from the lining of your GI tract. The large intestine absorbs water and changes the waste from liquid into stool. Peristalsis helps move the stool into your rectum.

Rectum. The lower end of your large intestine, the rectum, stores stool until it pushes stool out of your anus during a bowel movement .

Watch this video to see how food moves through your GI tract .

As food moves through your GI tract, your digestive organs break the food into smaller parts using:

- motion, such as chewing, squeezing, and mixing

- digestive juices, such as stomach acid, bile , and enzymes

Mouth. The digestive process starts in your mouth when you chew. Your salivary glands make saliva , a digestive juice, which moistens food so it moves more easily through your esophagus into your stomach. Saliva also has an enzyme that begins to break down starches in your food.

Esophagus. After you swallow, peristalsis pushes the food down your esophagus into your stomach.

Stomach. Glands in your stomach lining make stomach acid and enzymes that break down food. Muscles of your stomach mix the food with these digestive juices.

Pancreas. Your pancreas makes a digestive juice that has enzymes that break down carbohydrates, fats, and proteins. The pancreas delivers the digestive juice to the small intestine through small tubes called ducts.

Liver. Your liver makes a digestive juice called bile that helps digest fats and some vitamins. Bile ducts carry bile from your liver to your gallbladder for storage, or to the small intestine for use.

Gallbladder. Your gallbladder stores bile between meals. When you eat, your gallbladder squeezes bile through the bile ducts into your small intestine.

Small intestine. Your small intestine makes digestive juice, which mixes with bile and pancreatic juice to complete the breakdown of proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. Bacteria in your small intestine make some of the enzymes you need to digest carbohydrates. Your small intestine moves water from your bloodstream into your GI tract to help break down food. Your small intestine also absorbs water with other nutrients.

Large intestine. In your large intestine, more water moves from your GI tract into your bloodstream. Bacteria in your large intestine help break down remaining nutrients and make vitamin K . Waste products of digestion, including parts of food that are still too large, become stool.

The small intestine absorbs most of the nutrients in your food, and your circulatory system passes them on to other parts of your body to store or use. Special cells help absorbed nutrients cross the intestinal lining into your bloodstream. Your blood carries simple sugars, amino acids, glycerol, and some vitamins and salts to the liver. Your liver stores, processes, and delivers nutrients to the rest of your body when needed.

The lymph system, a network of vessels that carry white blood cells and a fluid called lymph throughout your body to fight infection, absorbs fatty acids and vitamins.

Your body uses sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, and glycerol to build substances you need for energy, growth, and cell repair.

Your hormones and nerves work together to help control the digestive process. Signals flow within your GI tract and back and forth from your GI tract to your brain.

Cells lining your stomach and small intestine make and release hormones that control how your digestive system works. These hormones tell your body when to make digestive juices and send signals to your brain that you are hungry or full. Your pancreas also makes hormones that are important to digestion.

You have nerves that connect your central nervous system—your brain and spinal cord—to your digestive system and control some digestive functions. For example, when you see or smell food, your brain sends a signal that causes your salivary glands to "make your mouth water" to prepare you to eat.

You also have an enteric nervous system (ENS)—nerves within the walls of your GI tract. When food stretches the walls of your GI tract, the nerves of your ENS release many different substances that speed up or delay the movement of food and the production of digestive juices. The nerves send signals to control the actions of your gut muscles to contract and relax to push food through your intestines.

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and other components of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) conduct and support research into many diseases and conditions.

What are clinical trials, and are they right for you?

Watch a video of NIDDK Director Dr. Griffin P. Rodgers explaining the importance of participating in clinical trials.

What clinical trials are open?

Clinical trials that are currently open and are recruiting can be viewed at www.ClinicalTrials.gov .

This content is provided as a service of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), part of the National Institutes of Health. NIDDK translates and disseminates research findings to increase knowledge and understanding about health and disease among patients, health professionals, and the public. Content produced by NIDDK is carefully reviewed by NIDDK scientists and other experts.

IMAGES

VIDEO