- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, benefit-sharing from protected area tourism: a 15-year review of the rwanda tourism revenue sharing programme.

- 1 School of Wildlife Conservation, African Leadership University, Kigali, Rwanda

- 2 School of Tourism and Hospitality, College of Business and Economics, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 3 Conservation Capital, Nairobi, Kenya

- 4 Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda

- 5 International Gorilla Conservation Program, Musanze, Rwanda

The success of protected areas depends to a large degree on the support of local communities living in and around these areas. Research has shown that where communities receive tangible and/or intangible benefits, from protected areas they are often more supportive of conservation. Rwanda introduced a tourism revenue sharing policy in 2005 to ensure that local communities receive tangible benefits specifically from protected area tourism and to enhance trust between the Rwanda Development Board (the then Rwanda Office of Tourism and National Parks) and local communities, and to incentivize the conservation of wildlife and protected areas. This study reviewed the tourism revenue sharing programme over the last 15 years, including primary and secondary data, which included interviewing more than 300 community members living around three national parks, as well as other relevant stakeholders. The results show that the tourism revenue sharing programme has resulted in a positive linkage between the national parks and development. Since 2005, ~80% of the funding was used for infrastructure and education projects. The funds are distributed through local community cooperatives, and most local people who are members of these cooperatives had received or were aware of tangible benefits received by the community and tended to have more positive attitudes toward tourism and the national parks. Despite a large amount of tourism revenue being disbursed over the 15-year period, there are still challenges with the programme and the overall impact could be enhanced. Recommendations as to how to address these are presented.

Introduction

Overview of benefit-sharing from protected area tourism.

If structured properly, tourism can contribute to local and national socio-economic development, as well as to conservation, directly and indirectly, within and around protected areas (PAs) ( Snyman and Spenceley, 2019 ). In Africa, particularly in eastern and southern Africa, tourism revenue is one of the major contributors to the financial sustainability of PAs and contributes to local community development, through employment, value chains and revenue-sharing programmes. For example, in Kenya 50% (US$ 30 million) of Kenya Wildlife Services' annual budget is generated from tourism, while in Zimbabwe 80% of the Zimbabwe Parks and Wildlife Management Authority's budget is derived from tourism ( Lindsey et al., 2020 ). Benefit-sharing programmes are often complex, involve numerous and diverse stakeholders, and have challenges in terms of equity, sustainability and good governance ( Snyman and Bricker, 2019 ). It is important, therefore, that benefit-sharing mechanisms and policies are reviewed and adapt and evolve over time to ensure that they are reaching the people who need them the most, and who are most directly and negatively impacted by a PA, mostly in terms of human-wildlife conflict (HWC) or restricted access to natural resources.

It is broadly recognized that the meaningful involvement of communities that live in and/or adjacent to PAs is critical to the long-term sustainability of these conservation areas ( Ahebwa et al., 2012 ; Dewu and Røskaft, 2018 ). Depending on their level of involvement, communities that live in, or adjacent to, PAs can be effective partners in conservation or can exacerbate threats to PAs, and sometimes it is a combination of both ( Kihima and Musila, 2019 ; Störmer et al., 2019 ). Ensuring that rural communities value conservation, through the receipt of tangible and intangible benefits, is critical to the long-term viability of PAs ( Dewu and Røskaft, 2018 ; Störmer et al., 2019 ). The basic premise is that if communities receive benefits, both tangible and intangible, from conservation and tourism in and around PAs, they will be more inclined to hold positive attitudes toward PAs and to conserve natural resources in PAs ( Kaaya and Chapman, 2017 ; Spenceley et al., 2017 ; Dewu and Røskaft, 2018 ; Snyman and Bricker, 2019 ; Ziegler et al., 2020 ). In addition, if local people can earn an income, or receive benefits through community-based tourism revenue sharing programmes (TRSPs), in turn, they will value wildlife and help protect it ( Wunder, 2000 ; Walpole and Thouless, 2005 ; Munanura et al., 2016 ).

There is no universal definition of revenue sharing. For the purposes of this study, we refer to the definition provided by Franks and Twinamatsiko (2017) : “ Revenue sharing is concerned with the arrangements for sharing a proportion of the protected area's income with local stakeholders to provide an incentive for them to support conservation .” In this study, stakeholders refer to indigenous and non-indigenous people that live within and/or around PAs.

Revenue is usually understood to be gross income rather than net income after the deduction of costs ( Franks and Twinamatsiko, 2017 ). The revenue shared may be in the form of cash payments but is usually disbursed in the form of small grants for selected projects. These may be projects for individual community members (i.e., micro-enterprises, school bursaries) or group projects that benefit part or all of the community (i.e., support for school infrastructure, road repair / development, or clinics).

Despite the benefits of revenue-sharing from PA tourism, there are also numerous challenges. Spenceley (2014) identified six key challenges with benefit-sharing from PAs, several of which were identified during this study as well. These include: (1) the value of money per person is small if divided among a large number of people; (2) benefits of social infrastructure (e.g., schools, water, infrastructure) are not always associated with the conservation or tourism; (3) those who benefit are not necessarily the same as those who experience the costs of conservation, [e.g., human-wildlife conflict (HWC) and loss of access to land)]; (4) poorest residents are often not the beneficiaries; (5) community entities may not have the capacity to partner with other stakeholders or to agree on benefit-sharing processes; and (6) legislation may constrain benefit-sharing processes (adapted from Spenceley, 2014 ).

Uganda and Rwanda are the only countries in Africa to have formal tourism-revenue sharing (TRS) policies that prescribe a specific amount to be shared. Research has been conducted ( Ahebwa et al., 2012 ; Tumusiime and Vedeld, 2012 ; Franks and Twinamatsiko, 2017 ; Twinamatsiko et al., 2018 ; Kambagira, 2019 ) on the tourism revenue-sharing programme (TRSP) in Uganda and has highlighted various challenges as well as benefits from the programme. The majority of the research either focused on one national park or community, rather than the TRSP as a whole. Similarly in Rwanda, research ( Imanishimwe et al., 2019 ; Mananura and Sabuhuro, 2020 ) has also been conducted on various elements of the TRSP, but the last full programme assessment was done in 2017, with a focus on Volcanoes National Park, rather than an overall longitudinal analysis of the TRSP across all national parks and including all major stakeholders. This study fills this gap as it assesses the TRSP over a 15-year period and included consultations with relevant stakeholders related to the three national parks receiving benefits over this period. The goal was to provide an updated comprehensive review of the whole TRSP in Rwanda and to provide policy- and practice-relevant recommendations, many of which could be incorporated into the Uganda TRSP as well as used to inform the development of other TRSPs globally. This study was requested by the Government of Rwanda because as a result of a recently declared a recently declared new protected area, they sought this opportunity to assess the programme, to-date and from there to determine how to adapt and amend the TRS policy to incorporate the new park and to meet the overall TRSP objectives as set out in the TRS Policy.

History of tourism revenue sharing in Rwanda

Rwanda's earliest form of benefit sharing was an informal model that dates back to the 1950s when the Belgians sought to increase cooperation with local communities bordering national game reserves by providing meat from problem animals ( Phiona and Jaya, 2015 ). Over the next five decades, benefit sharing programmes evolved across the country. In 2004, the Office Rwandais du Tourisme et des Parcs Nationaux (ORTPN) (now the Rwanda Development Board, RDB) allocated RWF 42 million (approx. US$ 75,000) from revenue generated in 2003 to the districts bordering the three NPs in the ratio of: 50% for Volcanoes National Park; 25% for Akagera National Park; and 25% for Nyungwe National Park. For this allocation, the district offices, guided by their specific district priorities, led in identifying which projects to fund [ Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2016 , 2017a , b ].

In October 2005, ORTPN formalized a TRSP that allocated 5% of the total revenue generated from three national parks (Akagera, Nyungwe and Volcanoes) to communities located in the areas surrounding the parks [ Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA), 2005 ].

When the Government of Rwanda (GoR) created its fourth national park, the Gishwati-Mukura National Park in 2015 [ Government of Rwanda (GoR), 2016 ], RDB expanded the TRS Policy to incorporate this new national parks in the TRSP. RDB also changed the TRS Policy in 2017 when they increased the Volcanoes National Park mountain gorilla trekking permit fee from US$ 750 to US$ 1,500. As a result of this increase, they also doubled the percentage of revenue allocated to the TRSP from 5 to 10% [ Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2017a ]. The 10% of pooled revenue from the national parks is now allocated according to the following ratio: 35%, Volcanoes National Park; 25%, Akagera National Park; 25%, Nyungwe National Park; and 15%, Gishwati-Mukura National Park. The GoR allocates an additional 5% of revenue to a HWC fund, which this study did not assess. The HWC fund is allocated for compensation due to HWC and is managed separately and not by RDB. Overall, within the zone of influence, the TRSP covers 14 districts and 51 sectors around the four NPs, with a total population of 1.4 million, with the largest population around Nyungwe National Park (538,000), followed by Volcanoes National Park (330,000), Akagera National Park (324,000); and Gishwati-Mukura National Park (21,500) [ Rwanda: Division in Sectors, 2017 ; Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2020 ].

The goal of the TRSP is to ensure sustainable conservation of the national parks by engaging the neighboring communities and contributing to the improvement of their lives. The TRSP outlines three impact objectives [ Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA), 2005 ], (i) Conservation impact objectives, which include to reduce illegal activities; ensure sustainable conservation; and increase community responsibility for conservation; (ii) livelihood impact objectives, to improve livelihoods by contributing to poverty reduction; to compensate for loss of access and/or crop damage; to provide alternatives to park resources; and encourage community-based tourism and (iii) relationship impact objectives (between national parks and the local population), to build trust; increase ownership reduce conflicts increase participation in conservation; and to empower communities.

Given the creation of the fourth NP in Rwanda and the increase in revenue-sharing from 5 to 10%, RDB is updating the TRS Policy to reflect the current situation and to enhance its impact. To adequately assess how best to revise the TRS Policy and related TRSP to create positive impact, RDB commissioned this study to review the impact of the TRSP over the last 15 years, including relevant stakeholder inputs, and to provide recommendations for improving impact.

Methods used in the research

The study utilized three data collection methods: desk research; field surveys in the three focal areas; and electronic and telephonic interviews of key stakeholders (physical meetings were not feasible due to COVID-19 restrictions). These methods were selected as the most comprehensive to ensure that relevant stakeholders were consulted to provide inputs into the review and to incorporate pertinent literature and prior assessments. The identification of key stakeholders was done in collaboration with RDB and the International Gorilla Conservation Programme (IGCP), who funded this research, to ensure that, to the extent possible, relevant stakeholders were included. A broader in-person stakeholder validation workshop was held on 18 May 2022 in Kigali, Rwanda where the results were presented and validated by 46 stakeholders, representing different districts, sectors, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and national government. A presentation of the results was done virtually by the lead author at the workshop and discussions were held regarding the recommendations, which were then revised and validated by the stakeholders.

For the desk-based research, the three main objectives were (i) to inform the data collection process as the desk research provided insights on prior TRSP assessments and identified the information gaps to be addressed during the data collection process; (ii) to understand key lessons learned, which was done through reviewing existing papers, reviews and assessments to help inform the team on challenges and opportunities of the TRSP, areas of impact, and barriers to success; and (iii) to provide examples of best practices of TRSPs from around the world, which was based on the desktop analysis, which assessed global models that RDB may want to consider with specific examples of positive impacts, challenges, and best practices in terms of the effectiveness and impact of the TRSP.

Non-exhaustive sources of information for the desk review included the following: publicly available publications, reports, and audits of the TRSP; key word searches in academic databases; documents provided by the RDB and IGCP; and relevant studies conducted and reports on TRSP developed by Conservation Capital (CC) and the African Leadership University (ALU).

Questionnaires where used to gather data in the communities surrounding the three focal NPs. The questionnaire was developed to determine level of awareness, views and perceptions of the TRSP benefits, challenges and opportunities for the future and data was specifically collected on the TRSP impacts; TRSP project selection; and TRSP project implementation.

The survey was designed to collect data from various stakeholder groups. These included: (i) the TRSP beneficiaries, which included individual cooperative and non-cooperative members; (ii) TRSP management and implementation stakeholders; and (iii) TRSP partners, including government, donors, NGOs.

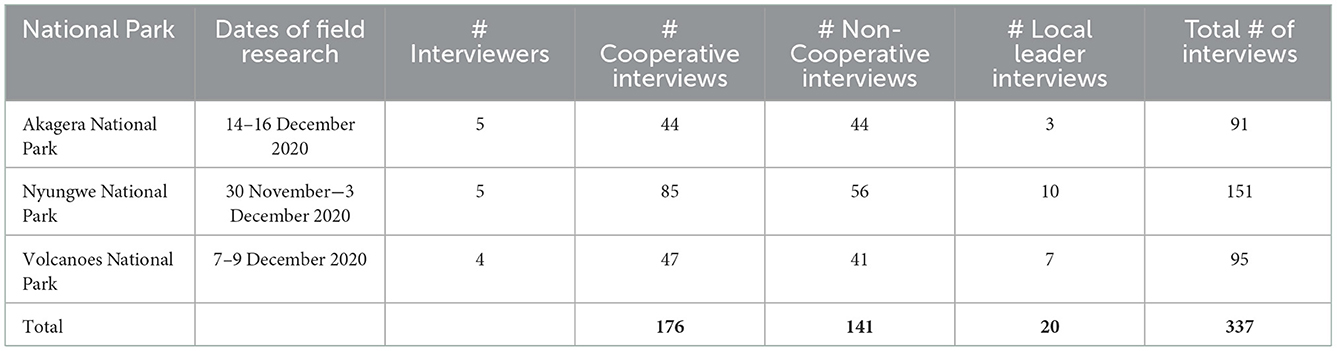

For the field interviews , administrative and logistical support was received from the IGCP and RDB and was conducted by the ALU from 30 November to 16 December 2020, with separate field trips to each of the three NPs. Gishwati-Mukura National Park was not included in the field research due to its recent inclusion in the TRSP: therefore, no disbursements having been done at the time of the research. Four ALU students, trained by the ALU School of Wildlife Conservation (SOWC), conducted the interviews, with support from the SOWC Director of Research at Nyungwe and an ALU SOWC faculty member at Akagera National Park. A distinction was made between cooperative [“ cooperatives are farms, businesses or other organizations, owned and run jointly by its members, who share the profits or benefits” ( Republic of Rwanda, 2018 )] and non-cooperative members as the TRSP only gives programme funds through cooperatives (local community members pay a small fee to be a member of a cooperative), as we wanted to determine if there were any differences in awareness and/or attitudes toward the TRSP and related conservation between those benefitting and those not directly benefitting. Local leaders around each of the NPs were also interviewed to provide an understanding of local leader attitudes to, and awareness of, the TRSP. See Table 1 for the interview schedule details.

Table 1 . Number of interviews conducted around the three national parks.

For the electronic questionnaire , the team used a similar questionnaire as the field interviews, which was uploaded onto a google platform. Participants from NGOs, private sector and government were invited to complete the survey. In addition, the team held telephonic interviews with key stakeholders. The online survey was shared with a total of 15 stakeholders of which 11 responded (73% response rate).

For the telephonic interviews, 12 were conducted (57% response rate) with a variety of stakeholders, including local and national government, conservation NGOs and private sector tourism operators.

The field research data, as well as the online survey and telephonic interview data was collated and analyzed in Excel, using descriptive statistics to calculate, describe, and summarize the collected data in the most efficient way.

The results are presented according to the different data collection methods used: (i) the desk review of how the TRSP funds have been allocated to-date and a review of past TRSP studies; (ii) the community interview results (including the local leader interview results); (iii) the online questionnaire results; and (iv) the telephonic interviews results. The online questionanarie and telephonic interview results were aggregated as they used the same questionnaire. The themes in the results section were selected to align with previous TRSP assessments done in Rwanda to allow for comparison if required.

Overview of the tourism revenue sharing programme funds to-date

Since its inception in 2005, the TRSP has invested RWF 5.8 billion (US$ 5.6 million) 1 in projects surrounding the four national parks. Volcanoes National Park, the largest contributor to the TRSP, saw the largest share of benefits with 41% of total project investment, with Akagera National Park, Nyungwe National Park, and Gishwati-Mukura National Park receiving 28, 26, and 5% 2 , respectively [ Rwanda Development Board (RDB), 2020 ].

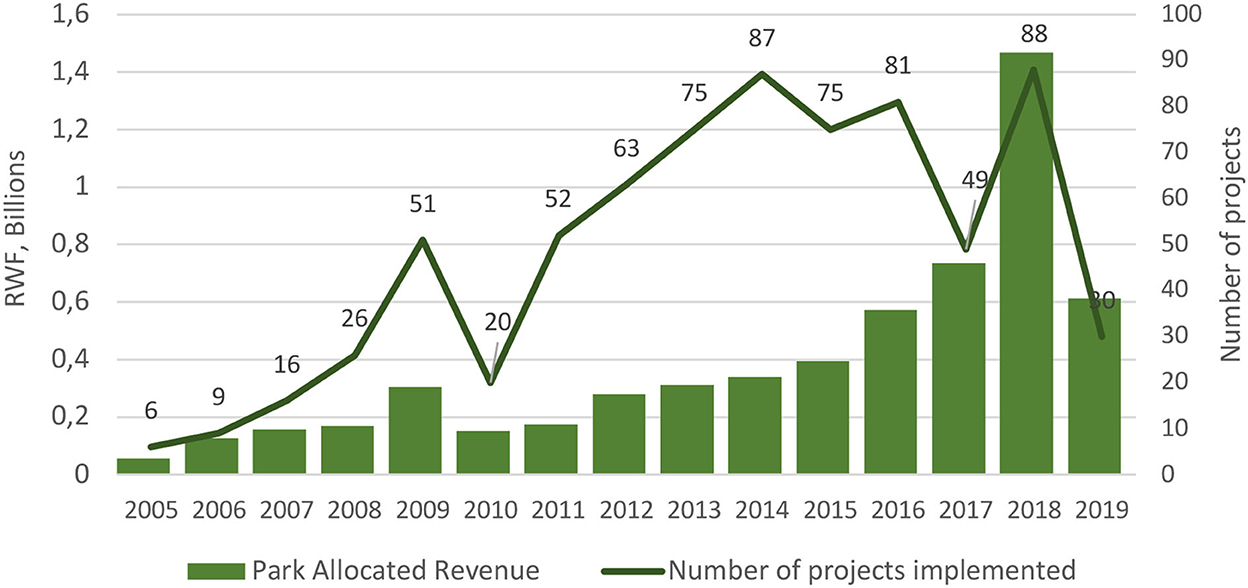

The number of projects supported by the TRSP has increased over the years, starting from five projects in 2005, and reaching an average of 65 projects per year between 2015 and 2019 (see Figure 1 ). The spike in project funding from 2017 to 2018 is related to the doubling of TRSP allocation from 5 to 10%, which corresponded with the increase in gorilla trekking fees from US$ 750 to US$ 1,500. This increase resulted in an increase in the average number of projects as well as in the budget made available per project. For example, the average project budget in 2015 was RWF 5.2 million (~US$ 5,000) (with 75 projects implemented); while in 2018, this number reached RWF 16.7 million (~US$ 16,100) (with 88 projects implemented). The 2019–2020 disbursement was impacted by COVID-19 and part of the allocation was used to purchase face masks for the community members around Volcanoes and Nyungwe NPs.

Figure 1 . Number of projects implemented through the TRSP per year from 2005 to 2019. RDB data, 2005–2019.

Projects funded by the TRSP fell into four major categories: infrastructure projects (80%); agriculture (15%); equipment purchase (2%); HWC (2%) and enterprise (1%).

Among the infrastructure projects, the largest allocation of funds went toward education projects (38% of all infrastructure projects), followed by housing (13%) and water supply (9%). The funded agricultural projects focused mostly on crop production and livestock (72% of all agricultural projects).

HWC support included mainly infrastructure support to prevent wildlife encroachment, such as a buffalo fence or a trench. The equipment purchase included items to support community development and livelihoods, such as milk and cassava processing plant equipment, sewing machines for local businesses, tannery equipment, carpentry equipment and transportation.

Desk review of prior studies

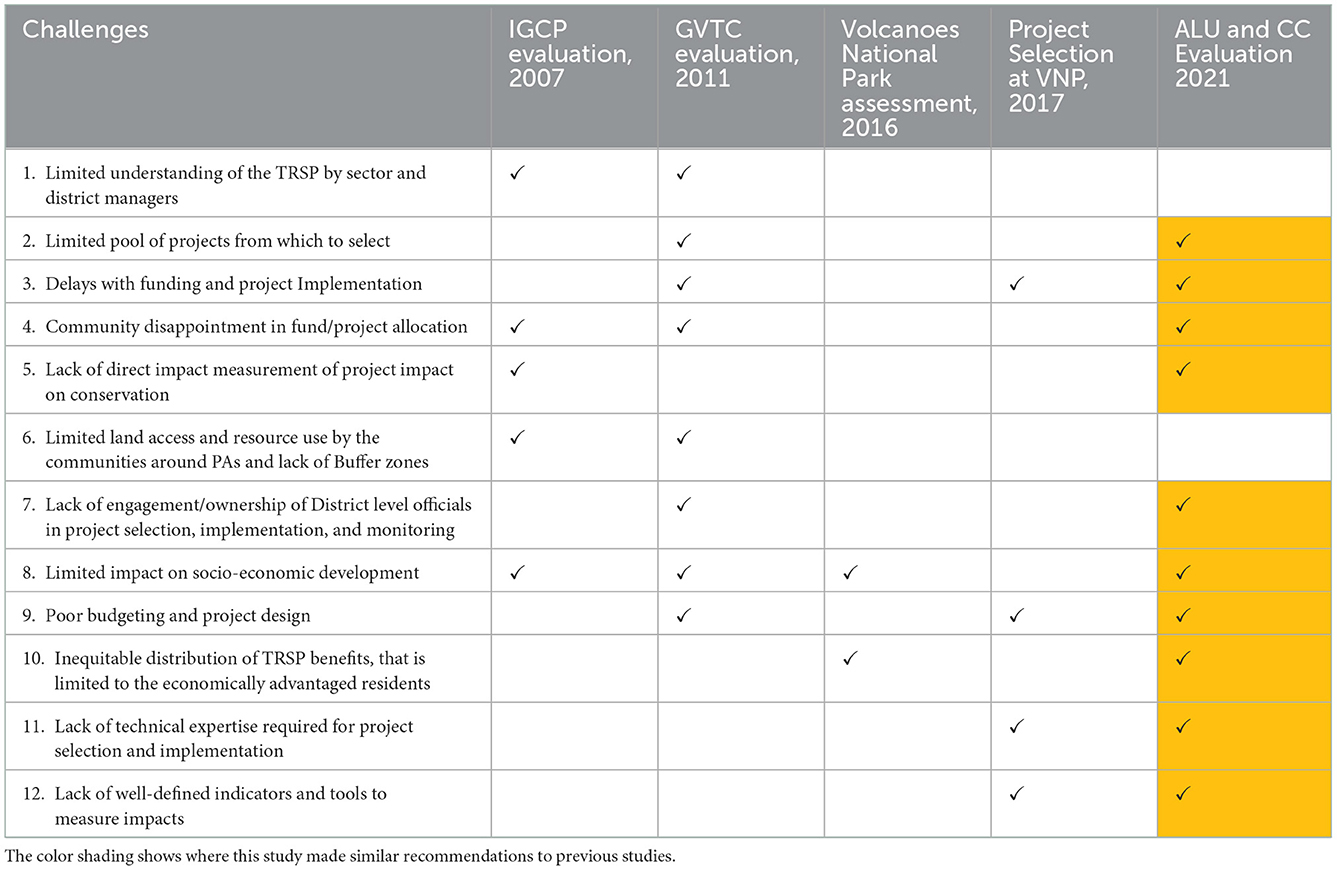

This study reviewed three prior assessments of Rwanda's TRSP [ International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP), 2007 ; Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC), 2011 ; Volcanoes National Park et al., 2015 ] and notes from a TRSP project selection meeting held at Volcanoes National Park. The challenges highlighted in the prior studies were reviewed and compared to the findings in this study (see Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Challenges highlighted in this as well as prior studies on the TRSP.

RDB has implemented several measures to meet some of the challenges (e.g., development of a new TRS Policy in 2020), however the results of the current assessment showed that a number of the challenges identified in prior studies remain.

Community interview results

The community interview results are presented per NP, aggregated for all three NPs together, and then broken down between cooperative and non-cooperative members to provide a complete analysis of the different groups interviewed.

Demographic data

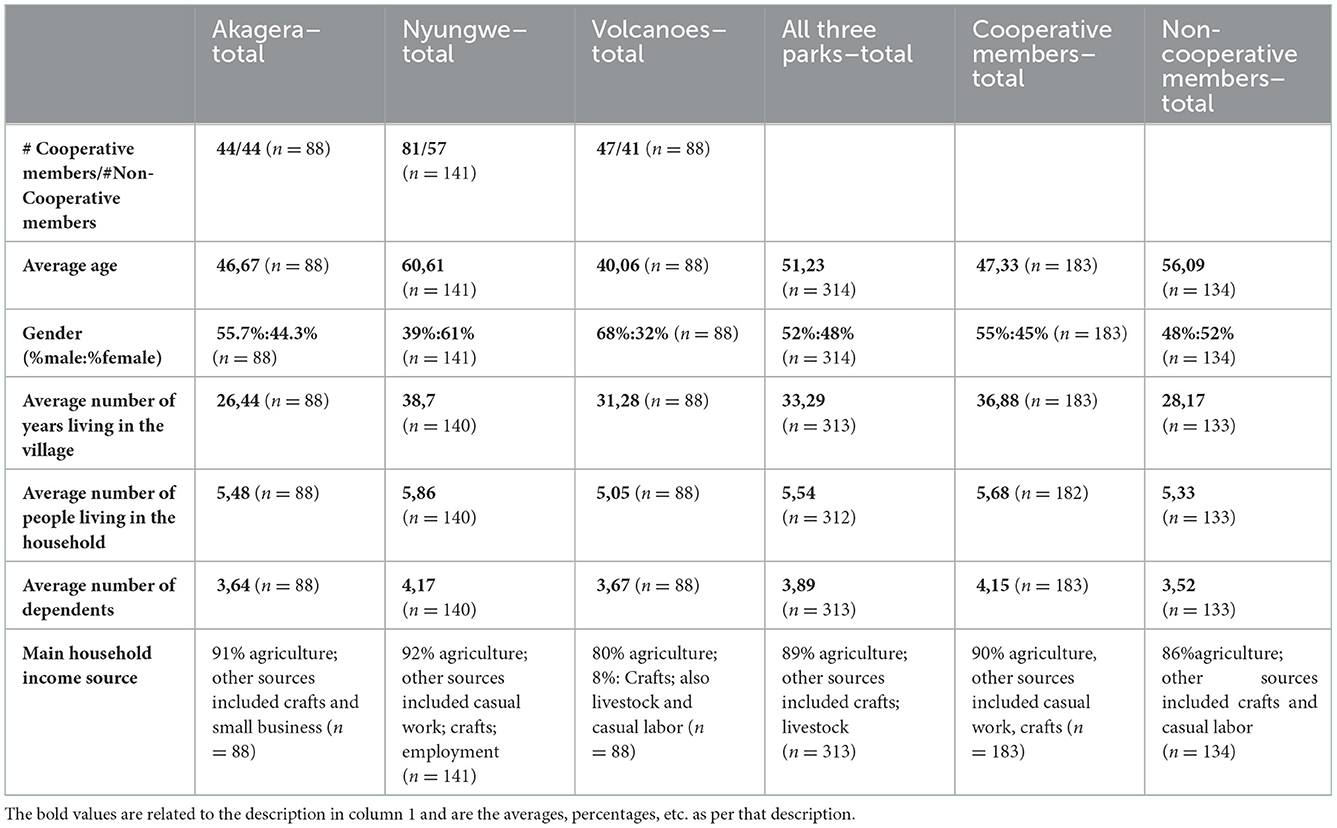

Table 3 shows the demographic information of participants in the field research, showing an average age of all those surveyed as 51.23 years, with 52% of respondents being male and 48% female. The main household income source for all participants was agriculture.

Table 3 . Demographic household data for the community surveys.

Awareness of TRSP

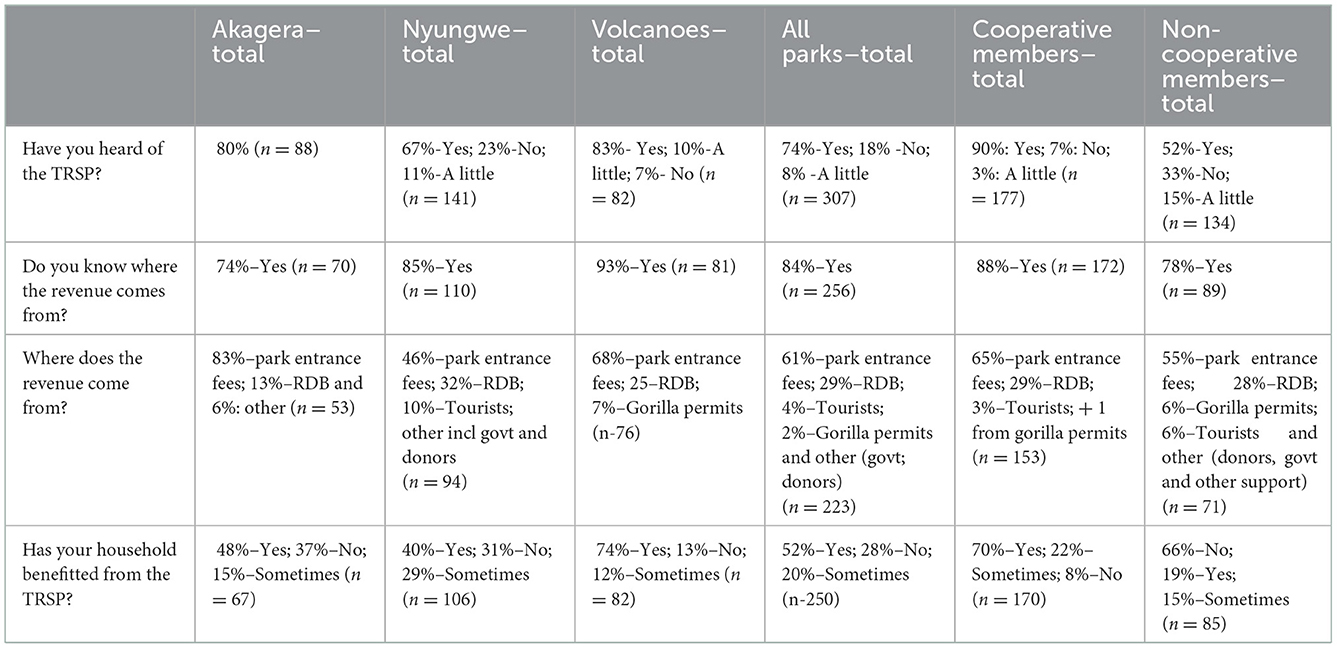

Table 4 presents results related to the awareness of the TRSP. As shown, an average of 74% of all respondents across the three NPs were aware of the TRSP, with Volcanoes National Park respondents having the highest awareness (83% of respondents had heard of the TRSP). This is likely because Volcanoes National Park, home to the mountain gorilla, has the largest number of international tourists with the highest revenues from gorilla permits and several visible TRSP projects conducted in the local community. The majority of participants (84%) said that they know where the revenue for the TRSP comes from, with cooperative members, in general, having greater awareness than non-cooperative members. When asked where the revenue comes from, some respondents said that it was from RDB rather than from tourism specifically, though the majority were aware of the connection to the NP and related tourism. Fifty-two percent of respondents said that their household had benefitted at some stage from the TRSP, with 74% of cooperative members saying they have benefitted while only 19% of non-cooperatives said so they had.

Table 4 . Community awareness of the TRSP.

Awareness of the project selection process

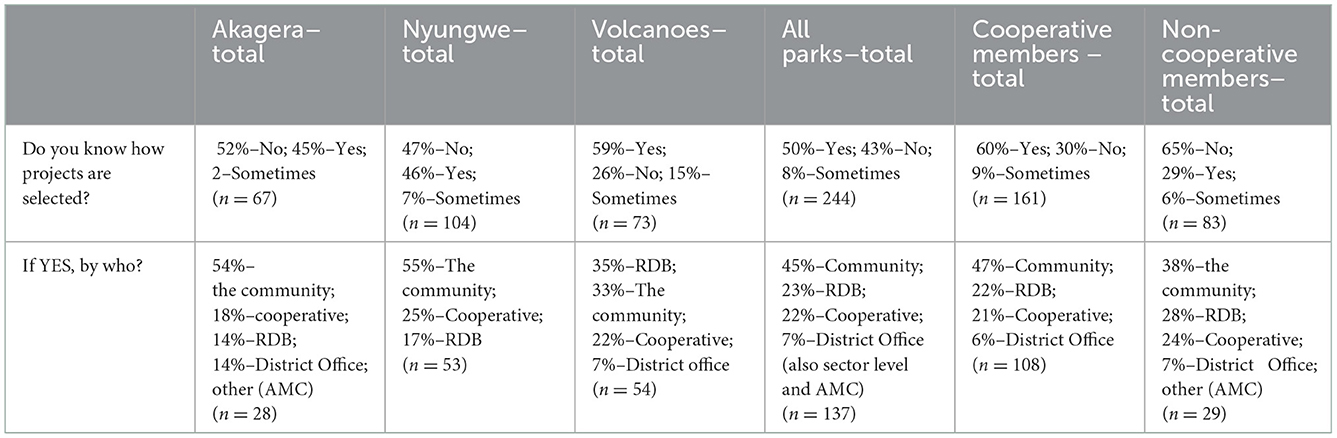

Fifty percent (50%) of the total respondents knew how TRSP projects were selected for funding, with Volcanoes National Park having the highest percentage (59%) ( Table 5 ). Forty five percent (45%) of community respondents said that the community were involved in the selection process, even among the cooperative respondents the percentage was less than half (47%).

Table 5 . Project selection process and implementation.

TRSP project assessment

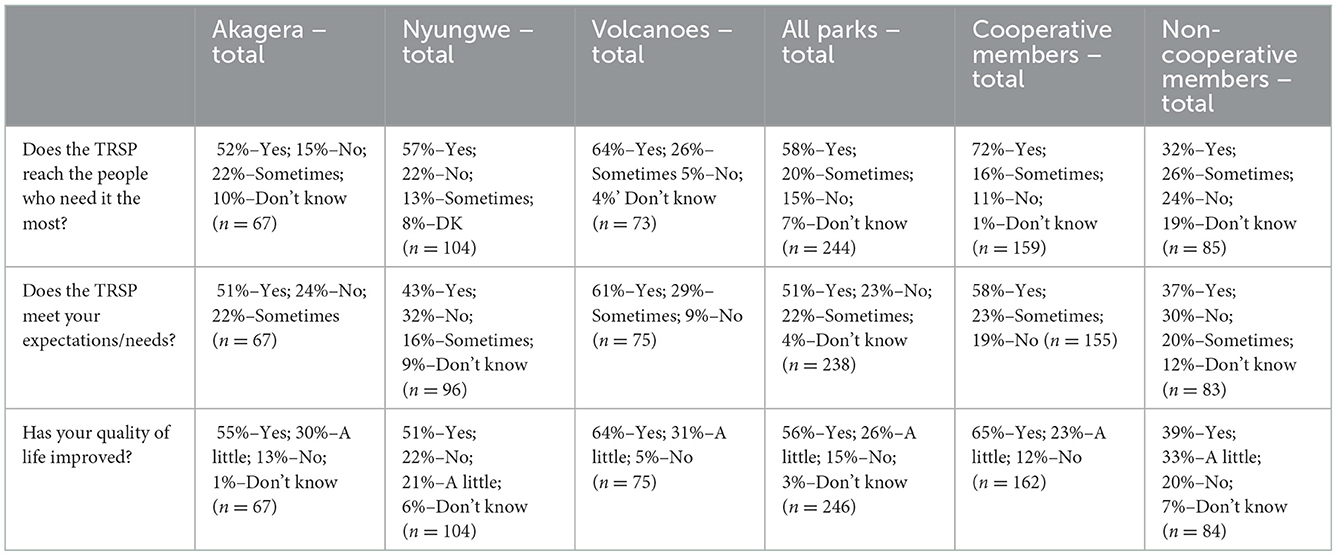

Table 6 presents an overview of respondents' assessment of the projects implemented with the TRSP funds. Fifty eight percent of all respondents felt that the TRSP funds reach the people who need it the most, though only 32% of the non-cooperative respondents felt so, compared to 72% of cooperative members. In terms of expectations, 51% of all respondents felt that the TRSP meets their needs/expectations: 58% for cooperative members and 37% for non-cooperative members. Fifty six percent of all respondents felt that their quality of life had improved as a result of the TRSP, whereas 65% of cooperative members felt that their quality of life had improved and 39% for non-cooperative members.

Table 6 . Tourism revenue sharing project assessment.

Satisfaction with the TRSP

Overall, 57% of respondents across all the NPs were satisfied with the TRSP; with 23% being very satisfied and 19% dissatisfied. Cooperative members (89%), who received the funds for projects, were generally more satisfied with the TRSP than non-cooperative members (63%). Overall, Nyungwe National Park had the highest number of participants who were satisfied (65%), followed by Volcanoes National Park (53%), then Akagera National Park (49%).

Eighty four percent of all community respondents felt that the TRSP has increased community support for conservation, while 95% of the respondents at Volcanoes National Park reported that it does.

Local leader interview results

The field research team also interviewed local leaders involved in the implementation of the TRSP to gain insights into their perspectives of the programme in terms of implementation and impacts on the livelihoods and attitudes of the local community.

Ninety five percent of the respondents were male (20 respondents in total, one female) and their roles in the TRSP were broken down as below, with the average number of years per respondent working in the TRSP being 7.16 years:

55%—Administration.

15%—Reviewer of proposals.

10%—Implementation of projects.

10%—Monitoring.

10%—Selection.

Respondents said that the main TRSP projects implemented were crop damage compensation and prevention measures and that the projects were developed by the cooperatives (68%), RDB (16%) and the community (11%). Given that the TRSP is different to the HWC fund, which supports crop damage compensation, it is clear that respondents were not aware of the difference, illustrating a lack of awareness of the objectives of the TRSP.

In terms of whether the TRSP projects have been developed on time, 32% said that they always were; 32% said sometimes; 21% frequently and 16% said that they were not developed on time. Forty seven percent of respondents said that the TRSP projects were developed as per the proposals/plans submitted, with 32% saying that they sometimes were and 16% saying that they frequently were. The main reasons indicated by respondents for projects not been developed according to the plan were a lack of financing and delayed financing.

Sixty one percent of respondents said that the community were always involved in the project selection process, while 22% and 11% reported being frequently or sometimes involved, respectively. Respondents who said that the community are involved said that they are involved mostly through choosing the project to submit and writing the proposal for the project, not in the decision-making in terms of project selection.

Sixty eight percent of respondents felt that the TRSP always reached the people who needed it the most, with 16% saying it frequently does, 16% saying it sometimes does and 11% saying that it does not. Seventy four percent of respondents said that information on the implementation process is communicated with the community. In terms of the TRSP projects corresponding to community needs/expectations: 55% of respondents said they do; 25% said that they sometimes do and 20% said that they do not. Eighty nine percent of respondents said that they think that the TRSP projects increase community support for conservation.

In terms of TRSP projects leveraging additional funding, 37% said that they sometimes do, 32% said that they do, 16% said that they do not and 16% said that they do not know. Respondents said that leveraged funding usually came from national (sometimes local) government and that it was mostly education projects, which leveraged additional funding, as well as conservation and HWC mitigation projects.

Fifty nine percent of respondents felt that the TRSP funding does not replace government funding, but 29% felt that it does and 12% did not know.

Respondents said the main successes of the TRSP are related to employment and infrastructure and the main challenges of the TRSP were that the proposals were not good enough; there were issues with implementation; there was a lack of connection to conservation; and the process for selecting projects wasn't always clear.

Overall, 53% of respondents were satisfied with the TRSP; 37% very satisfied and 11% dissatisfied.

Interview and online survey results

This section presents the results from the telephonic interviews and the online survey summarizing respondents' impressions of the TRSP in terms of conservation, their awareness of the TRSP and its achievements. In this section the term ‘respondents' collectively refers to to NGOs, private sector partners and government representatives unless otherwise specified.

TRSP impact on conservation

While it is difficult to attribute the direct impact of the TRSP on conservation, the survey results reveal that interviewed stakeholders recognized the role of the TRSP in conservation efforts. Eight out of 11 (73%) respondents indicated that the TRSP always, frequently or sometimes played a role in decreasing illegal activities, and nine out of 11 (82%) indicated that always, frequently or sometimes TRSP-supported projects increased community support for conservation.

TRSP awareness

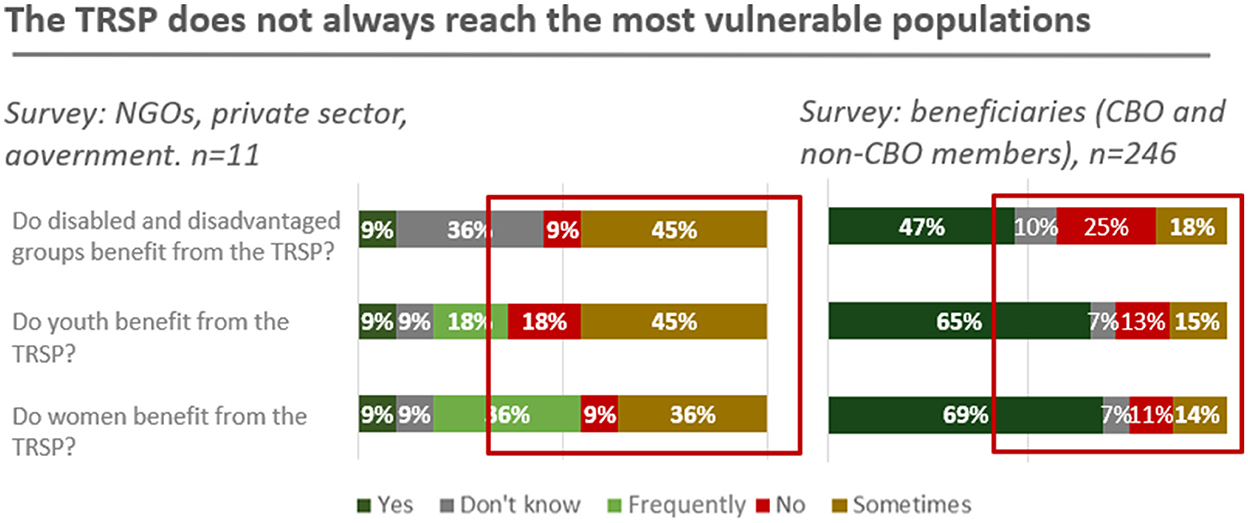

Half of the respondents indicated that disadvantaged, women, and youth either did not benefit at all or occasionally benefited from the TRSP ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 . Awareness of the TRSP. Survey NGO, private sector and government, n = 11.

TRSP achievements

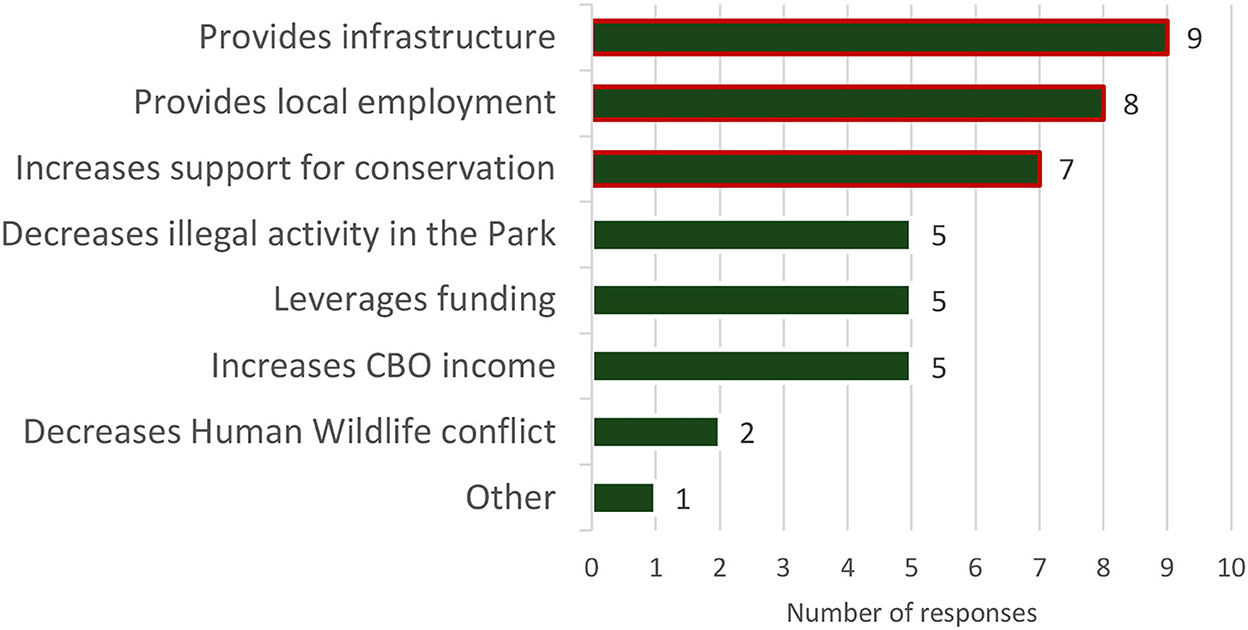

Partner organizations viewed the main achievements of the TRSP to be infrastructure development, employment creation, and conservation support ( Figure 3 ).

Figure 3 . Main successes of the TRSP as indicated by partner organizations.

Funding alignment with community needs

A majority (64%) of the respondents indicated that the TRSP sometimes meets community expectations and needs and 36% indicated that the programme frequently or always meets their needs.

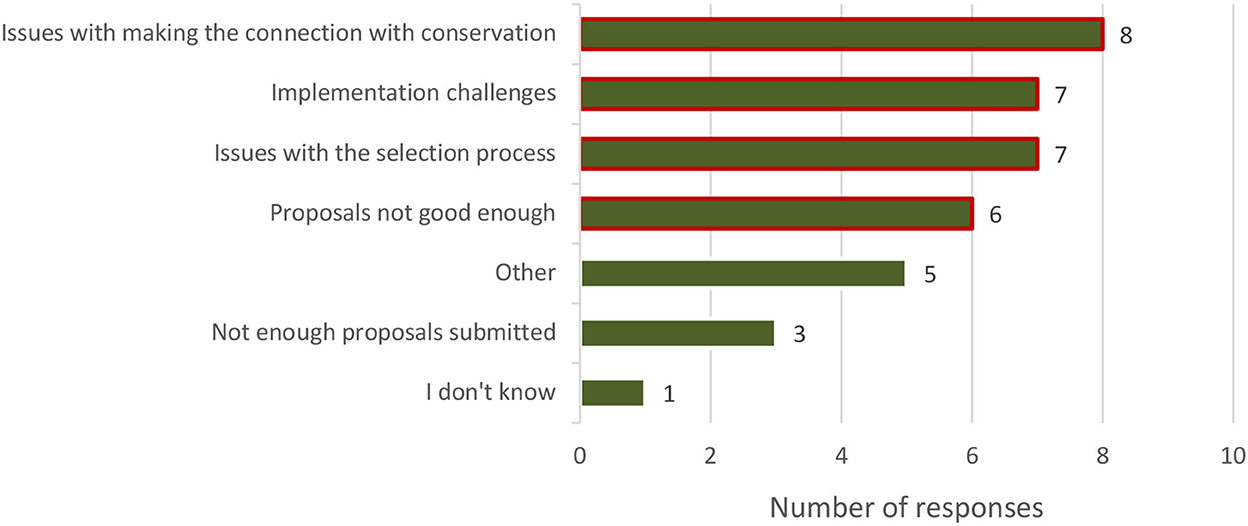

TRSP challenges

A majority (73%) of the respondents indicated the top four challenges of the TRSP are: making the connection between the TRSP and conservation; implementation challenges; issues with the selection process; and proposals not being good enough ( Figure 4 ).

Figure 4 . The main challenges of the TRSP highlighted by partner organizations. Survey NGOs, private sector and government representatives, n = 11.

Community involvement

When asked about community involvement in the TRSP, 45% of respondents think that communities are either not involved at all or involved on an irregular basis in project selection, with many feeling that project selection is determined by the district office.

Project selection transparency

Respondents indicated that there is a lack of overall clarity on the project selection process. Nine percent of the respondents said there is sometimes clarity and 27% said there is no clarity on the process for selecting projects. This is markedly different to the response from the communities, where 65% of non-cooperative members indicated that the process is not clear; whereas 60% of cooperative members indicated that the process is clear.

Monitoring of the TRSP projects

When asked whether the TRSP-selected project implementation progress is regularly monitored, 27% of the respondents indicated no and 27% indicated they did not know.

Stakeholders surveyed and interviewed attributed community support for conservation to the TRSP and its related benefits and stated that the TRSP has developed infrastructure and created jobs. However, they indicate that overall, the TRSP is not meeting the needs of the community and in particular those of the marginalized community members and non-cooperative members, and that there are challenges with implementation and proposal development. In addition, they indicate that the communities are not fully involved in the whole TRSP process.

Only small differences existed between the community respondents and other stakeholders in their awareness of and satisfaction with the TRSP. Overall, the results highlight a general lack of awareness of how projects are selected and a perception that the community is not fully involved in the TRSP and that it is largely driven by the distrcit offices. This was similarly found by Tumusiime and Vedeld (2012) in their study on Uganda's TRSP where they found that there was no real local community participation. Interestingly, in our study partner organizations were less positive about the TRSP meeting community needs/expectations than the community members or the local leaders. More of the local leaders felt that the community were more involved in the selection process (61%) than the partner organization respondents (55%) and only 45% of the community respondents felt so. This indicates that the majority of the main target group—local communities—did not feel part of the selection process.

All groups, including 89% of the local leaders, 84% of community respondents, and 82% of the partner organizations, felt strongly that the TRSP has increased the community support for conservation. The overall percentage of local leader respondents who were satisfied with the TRSP (53%) is aligned with that of the community respondents (57%).

Many of the overall weaknesses identified by the various respondent groups have been previously identified in other studies [ International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP), 2007 ; Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC), 2011 ], particularly in terms of challenges in implementation and the impact on socio-economic development. The recommendations below are based on the results of the primary and secondary research conducted for this study, which were further confirmed by prior assessments. There are several recommendations put forward to improve the overall impact of the TRSP in Rwanda and to ensure a greater understanding of the impacts through better monitoring and evaluation of projects and where and how funds are being spent.

Over the past 15 years, the results of this and previous studies ( Phiona and Jaya, 2015 ; Munanura et al., 2016 ) show that Rwanda's TRSP has met many of the programme's objectives, including creating support for conservation from local communities, generating awareness of conservation and the value of wildlife and PAs, building relationships between RDB and the communities, enhancing the lives of community members and developing infrastructure throughout the NP regions. Rwanda now has developed high quality infrastructure in the focal areas with strong support from local residents for conservation through the TRSP.

The main challenges identified in this study are effective community engagement, reaching the most vulnerable, and ensuring that the TRSP meets community needs. Having requested this study, the GoR is interested in adapting the TRS Policy to more effectively engage the communities living around the PAs in the TRSP and to allocate more funding to directly enhance the lives of Rwandan citizens living around PAs. We recommend that this can be done by involving communities more in the entire TRSP process, making the TRSP more accessible to all community members and allocating more funds to community development programmes proposed and selected by the communities themselves.

Based on the study's results, the following recommendations are made to enhance the TRSP and simultaneously support RDB's role as a leader in innovative community conservation. These recommendations can also be taken into consideration by other countries interested in developing and/or improving community engagement in, and benefits, from TRSPs.

i. Revise the revenue allocation model and eligibility to create resilience .

A majority of the TRSP revenue over the past 15 years has supported infrastructure development. A majority of the respondents consulted urged the GoR to rather allocate a majority of the TRSP revenue to livelihood development programmes. These programmes have the potential to enhance the resiliency of communities, create jobs, diversify revenue (reducing reliance directly on tourism, which is particularly important given the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic) and to garner further conservation support from the communities.

It is recommended that the following percentages be used for the revenue allocation going forward: 70% for livelihood projects; 25% for infrastructure support; and 5% in an emergency fund. Equipment would fall under either livelihood projects or infrastructure support, depending on the project. HWC compensation is already covered by the HWC fund. The emergency fund would be used during times of crisis, such as COVID-19, when tourism revenue is severely impacted. The use of the funds would be guided by the updated TRS Policy and the funds should go into an interest-bearing account managed by RDB. Once the funds reach US$ 150,000 (RWF 1.5 million), the 5% should be allocated to livelihood projects. This amount was calculated by doubling the average annual spend of the TRSP, to ensure that the TRSP would have enough funds for 2 years in a time of crisis. Should there not be a suitable number of livelihood projects proposed by the community, the balance of the funds could be allocated to infrastructure projects. If community members propose a livelihood project that includes infrastructure, such as a shop, this should be included under livelihood projects and not infrastructure.

The TRSP is currently limited to providing funding to cooperatives. Stakeholders indicated that this excludes the most vulnerable community members, as most cooperatives require a membership fee. It is, therefore, recommended that the selection criteria should include individual groups, if projects benefit more than 10 households, as well as NGOs working with and selected by the communities. Inclusion of the most vulnerable community members is a target in the existing TRS Policy and is likely to remain a focus for the GoR in the revised policy.

It is also recommended that proposals for community capacity building (which are not currently permissible) should also be permissible (see recommendation five).

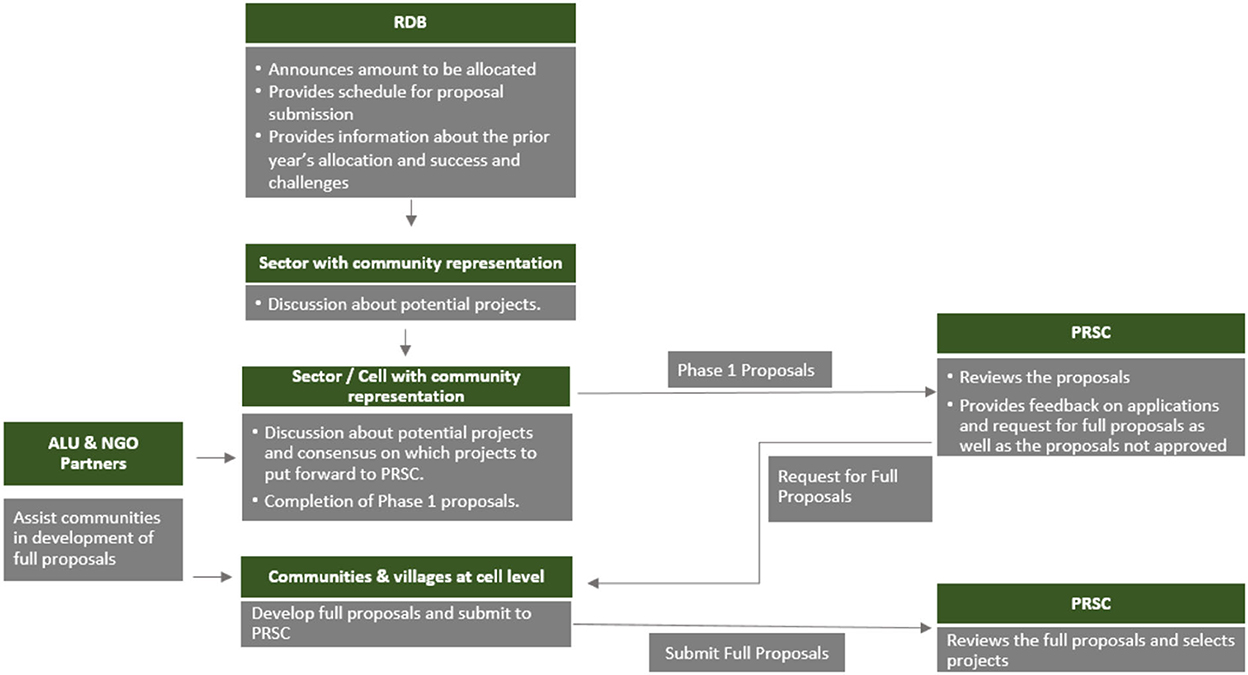

ii. Clarify and create awareness around the TRSP process .

There was a general lack of clarity about the TRSP cycle and process, from identification and selection of potential projects to monitoring and evaluation. Stakeholders indicated that the District Offices ultimately decide which projects are selected, not the communities. The current selection process includes three key steps: (1) communities develop project proposals; (2) the District Technical Committee screens and short lists the proposals; and (3) Park Revenue Sharing Committee (PRSC) selects the projects [ Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA), 2005 ]. The following are recommended:

a. Clarify the selection criteria used to select projects and make this public (and available in the local language) with clear definitions to avoid ambiguity and misinterpretation and to be accessible to to the entire population.

b. Develop and make accessible a programme schedule that makes it clear when proposals are due and when selection will take place. This should be the same every year to ensure consistency.

c. Publicize the list of the Park Revenue Sharing Committee members to create full transparency, accountability, and awareness.

d. Simplify the proposal submission procedure and adopt a two-step proposal process, which will make the application process more accessible and save time for the applicants as well as the reviewers:

• Step 1. Submission of a simple standard application form that is accessible to communities, which includes an option to request support for the full proposal if selected and if needed by the applicant; and

• Step 2. For those selected, a full proposal with standard template available, including a list of the required supporting documents.

e. A project awards ceremony would help launch projects and provide more visibility to the communities and relevant stakeholders on selected projects. This would also help create accountability for the project implementer.

iii. Enhance community involvement throughout the TRSP process .

It is recommended that the project selection process should be more inclusive of and engaging for local communities, who currently feel excluded from the process. The process should be initiated at the sector or cell level were projects would be deliberated by the community to determine collectively which proposals to submit; thus, ensuring community ownership for the decision. Communities should also be represented on the Park Revenue Sharing Committee; thus, part of the final vetting and selection process (see Figure 5 ). Decentralizing decision making and effectively engaging local communities in the process will build capacity as well as support for conservation.

Figure 5 . Recommended TRSP project cycle.

iv. Enhance project execution .

Programme delays resulting from the flow of funding were reported as an issue for effectively and timeously implementing projects. The TRSP funding currently goes through the local government. To enhance efficiency, funding should be transferred directly to the implementing organizations and when needed, NGOs selected by the community, can serve as fiscal agents until capacity is developed.

Implementation can be done, if needed, by an NGO or the private sector (selected by the community) that has the required skills and expertise, and part of the process can be to build the capacity of the community organization.

v. Support capacity for communities, local government and RDB .

Lack of capacity and skills were identified in the qualitative comments as one of the major barriers for community participation, programme management and project implementation. Capacity building should be embedded into the entire TRSP process from supporting communities in the application process to project implementation and monitoring. NGOs and private sector partners operating in all the NP landscapes can help provide capacity support and help with implementation, which will help leverage other programmes in the area. In some cases, capacity building is needed for local government and staff working on the TRSP as well. The TRSP could be used to finance these capacity support programmes.

vi. Enhance monitoring and evaluation .

The capturing of data and information to better inform the TRSP, support adaptive management, and guide other PA revenue-sharing programmes in Africa and around the world is critical. While project verification procedures are stipulated in the TRS Policy, this is rarely followed due to a lack of capacity, and there is an overall lack of clarity on, and understanding of, the monitoring process among partner organizations and a lack of capacity for monitoring and evaluation (M&E). As a result, the following are recommended:

• At a minimum, there should be recruitment of one monitoring and evaluation senior officer fully dedicated to reviewing, monitoring, and reporting on the TRSP. This position could be financed through the TRSP.

• While ultimate responsibility and accountability rests with the monitoring and evaluation senior officer, he/she should develop a system for monitoring as well as relevant tools and should train and engage stakeholders in monitoring and evaluation. Monitoring smart phone platforms that community members can use for project planning, execution and monitoring could also be considered.

The aim of these recommendations is to ensure greater direct community involvement and overall stakeholder awareness and understanding of the TRSP as well as a greater connection between local communities to conservation resulting in greater support for conservation, pride in Rwanda's natural areas and improved livelihoods. In addition, with greater coordination with communities, private sector and NGOs, the TRSP can be used to leverage other funding and to use existing resources more efficiently.

Rwanda has one of the highest revenue sharing programmes, in terms of percentage revenue allocated to the programme, in Africa. Over the past 15 years, the TRSP has financed infrastructure, supported community livelihoods, and established a positive linkage to, and support for, conservation. Despite the TRSP having achieved positive results, various reviews have highlighted challenges with the programme. It was found in the secondary research for this study that many of the past recommendations to improve the TRSP have not been implemented and several of the same challenges exist. It is likely that this is due to the complexity of implementing many of the recommendations due to the diversity of stakeholders involved, lack of capacity within the government to implement recommendations, and the size of the beneficiary population. Although this study attempted to engage with as many relevant stakeholders as possible, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some limitations with access and in-person meetings.

Ultimately, given the vision of the TRSP (community support, conservation linkages, and relationship building with RDB), changes are recommended to ensure that the community are directly engaged in the TRSP, benefitting from it and seeing the linkages between it and the related conservation. A number of the challenges faced by the Rwanda TRSP are similarly faced by other country TRSPs, highlighting that tourism-revenue sharing is complex, with a diversity of stakeholders and dependent on an industry that has also been shown to be volatile and vulnerable to shocks. The recommendations in this study have, therefore, also sought to build greater resilience in the TRSP and to reduce long-term risks. The commissioning of this study by the GoR demonstrates a keen interest in understanding the challenges and how to improve the TRSP, which is a critical first step. Incorporating communities into the entire TRSP process, allocating more revenue to community livelihoods than infrastructure projects, embedding capacity building into the programme and supporting monitoring and evaluation will further enhance the TRSP and help achieve its goals, which will support Rwanda's ambitious conservation and community goals.

As Gishwati-Mukura National Park was only added to the TRSP in 2019, it was not included in the field research as it will take time for the impacts of the TRSP to be felt. It is, therefore, recommended that baseline field research be conducted around Gishwati-Mukura National Park as soon as possible to measure the impacts of the TRSP more accurately over time. This will provide an opportunity to directly assess the impact of the TRSP before and after funds have been distributed. More detailed research on poverty level indicators should also be included in annual monitoring of the TRSP in order to have updated, robust data on impacts, rather than focusing on outputs and outcomes of the TRSP.

Data availability statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data was collected for the government of Rwanda, so we would need to get their permission to share if requested. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to SS, ssnyman@alueducation.com .

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

SS and KF conceived and designed the analysis, collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, performed the analysis, and wrote the paper. AB collected the data, contributed data or analysis tools, and performed the analysis. BM and TN conceived and designed the analysis and provided logistical support. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding for this research was received from the International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP) for funding this research and to the Rwanda Development Board for their support with collating documents and identifying stakeholders. Thank you to all the public, private, NGO and community participants who engaged in the surveys and consultations and also to the ALU SOWC students who conducted the community interviews around the three national parks.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ As of 27 April 2022 exchange rate. https://www1.oanda.com/ .

2. ^ Gishwati-Mukura was integrated into the TRSP in 2019.

Ahebwa, W. M., van der Duim, R., Sandbrook, C. (2012). Tourism revenue sharing policy at Bwindi Impenetrable National Park, Uganda: A policy arrangements approach. J. Sustain. Tour. 20, 377–394. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2011.622768

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dewu, S., Røskaft, E. (2018). Community attitudes towards protected areas: Insights from Ghana. Oryx 52, 489–496. doi: 10.1017/S0030605316001101

Franks, P., Twinamatsiko, M. (2017). Lessons Learnt from 20 Years of Revenue Sharing at Bwindi Impenetrable . IIED report. Available online at: http://pubs.iied.org/17612IIED

Google Scholar

Government of Rwanda (GoR). (2016). ‘Law No45/2015 OF 15/10/2015 Establishing the Gishwati-Mukura national park', Official Gazette n° 05 of 01/02/2016, 104-108 . Government of Rwanda (GoR) 2016 - Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda.

Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC). (2011). Assessment of the Performance of the Revenue Sharing Programme During 2005-2010. Greater Virunga Transboundary Collaboration (GVTC), Kigali, Rwanda.

Imanishimwe, A., Niyonzima, T., Nsabimana, D. (2019). Comparing the community dependence on natural resources in Nyungwe National Park and the contribution of revenue sharing through integrated conservation and development projects. Afr. J. Online 2. doi: 10.4314/rjeste.v2i1.9

International Gorilla Conservation Program (IGCP). (2007). Evaluation des projets financés par les revenus issus du tourisme . International Gorilla Conservation Programme, Kigali, Rwanda

Kaaya, E., Chapman, M. (2017). Micro-credit and community wildlife management: complementary strategies to improve conservation outcomes in Serengeti National Park, Tanzania. Environ. Manage. 60, 464–475. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0856-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Kambagira, A. (2019). Tourism resource distribution and development in Uganda. A case of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park (Ph. D. dissertation). Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda.

Kihima, B. O., Musila, P. M. (2019). Extent of community participation in tourism development in conservation areas: A case study of Mwaluganje Conservancy. Parks 25, 47–56. doi: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2019.PARKS-25-2BOK.en

Lindsey, P., Allan, J., Brehony, P., Dickman, A., Robson, A., Begg, C., et al. (2020). Conserving Africa's wildlife and wildlands through the COVID-19 crisis and beyond. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 4, 1300–1310. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1275-6

Mananura, I. E., Sabuhuro, E. (2020). “The potential of tourism revenue sharing policy to benefit conservation in Rwanda,” in Routledge Handbook of Tourism in Africa . London, United Kingdom: Routledge.

Munanura, I. E., Backman, K. F., Hallo, J. C., Powell, R. B. (2016). Perceptions of tourism revenue sharing impacts on volcanoes national park, rwanda: a sustainable livelihoods framework. J. Sustain. Tour. 24, 1709–1726. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2016.1145228

Phiona, K., Jaya, N. E. (2015). The effectiveness of rwanda development board tourism revenue sharing program towards local community socioeconomic development: a case study of Nyungwe National Park. Eur. J. Hospital. Tour. Res. 3, 47–63. Available online at: http://www.eajournals.org/wp-content/uploads/The-effectiveness-of-Rwanda-Development-Board-tourism-revenue-sharing-program-towards-local-community-socio-economic-development.pdf

Republic of Rwanda (2018). Ministry of Trade and Industry, National Policy on Cooperatives in Rwanda: “Toward Private Cooperative Enterprises and Business Entities for Socio-Economic Transformation” . Available online at: http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/rwa193693.pdf (accessed on September 2, 2021).

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2017a). Increase of Gorilla Permit Tariffs | Official Rwanda Development Board (RDB) Website . Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda. Available online at: https://rdb.rw/increase-of-gorilla-permit-tariffs/ (accessed on December 2, 2020).

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2020). Tourism Revenue Sharing in Rwanda: Policy and Guidelines. Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda.

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2016). Revenue Sharing 2016–2017: Projects' Selection Report . Musanze.

Rwanda Development Board (RDB). (2017b). Revenue Sharing 2017–2018: Projects' Selection Report . Musanze.

Rwanda Wildlife Authority (RWA). (2005). Tourism Revenue Sharing in Rwanda-Provisional Policy and Guidelines. Office Rwandais du Tourisme et des Parcs Nationaux, Kigali, Rwanda.

Rwanda: Division in Sectors (2017). Available at https://www.citypopulation.de/en/rwanda/sector/admin/ (accessed on January 14, 2021).

Snyman, S., Bricker, K. S. (2019). Living on the edge: benefit sharing from protected area tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 705–719. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2019.1615496

Snyman, S., Spenceley, A. (2019). Private Sector Tourism in Conservation Areas in Africa. Wallingford, Oxfordshire: CABI, Oxford.

Spenceley, A. (2014). Tourism Concession Guidelines for Transfrontier Conservation Areas in SADC . Report to GIZ/SADC. Retrieved from https://tfcaportal.org/sites/default/files/public-docs/tourism_concession_guidelines_sadc_tfcas_final.pdf (accessed on May 12, 2020).

Spenceley, A., Snyman, S., Rylance, A. (2017). Revenue sharing from tourism in terrestrial African protected areas. J. Sustain. Tour. 27, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2017.1401632

Störmer, N., Weaver, L. C., Stuart-Hill, G., Diggle, R. W., Naidoo, R. (2019). Investigating the effects of community-based conservation on attitudes towards wildlife in Namibia. Biol. Conserv. 233, 193–200. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.02.033

Tumusiime, D. M., Vedeld, P. (2012). False Promise or false premise? Using tourism revenue sharing to promote conservation and poverty reduction in Uganda. Conserv. Soc. 10, 15–28. doi: 10.4103/0972-4923.92189

Twinamatsiko, M., Baker, J., Franks, P., Infield, M., Olsthoorn, F., Roe, D. (2018). An Overview of Integrated Conservation and Development in Uganda. London, United Kingdom: Routledge. Available online at: https://www.google.com/search?q=London&stick=H4sIAAAAAAAAAOPgE-LUz9U3ME4xzStW4gAxTbIKcrRUs5Ot9POL0hPzMqsSSzLz81A4Vmn5pXkpqSmLWNl88vNS8vN2sDLuYmfiYAAALM0efE8AAAA&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiQ6O_0por8AhWVnnIEHYSyAxEQmxMoAHoECGEQAg

Volcanoes National Park Rwanda Development Board, and Janvier, K. (2015). Revenue Sharing Projects-Selection, Exercise 2015: The Minutes of the Workshop . Rwanda Development Board, Kigali, Rwanda.

Walpole, M. J., Thouless, C. R. (2005). “Increasing the value of wildlife through non-consumptive use? Deconstructing the myths of ecotourism and community-based tourism in the tropics” in People and Wildlife: Conflict or Coexistence? , eds. R. Woodroffe, S. Thirgood, A. Rabinowitz (2005). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 122–139.

Wunder, S. (2000). Ecotourism and economic incentives—an empirical approach. Ecol. Econ. 32, 465–479. doi: 10.1016/S0921-8009(99)00119-6

Ziegler, J., Araujo, G., Labaja, J., Snow, S., King, J. N., Ponzo, A., et al. (2020). Can ecotourism change community attitudes toards conservation? Oryx 55, 546–555. doi: 10.1017/S0030605319000607

Keywords: tourism, protected areas, revenue-sharing, conservation, development, Rwanda, local communities

Citation: Snyman S, Fitzgerald K, Bakteeva A, Ngoga T and Mugabukomeye B (2023) Benefit-sharing from protected area tourism: A 15-year review of the Rwanda tourism revenue sharing programme. Front. Sustain. Tour. 1:1052052. doi: 10.3389/frsut.2022.1052052

Received: 23 September 2022; Accepted: 19 December 2022; Published: 03 February 2023.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2023 Snyman, Fitzgerald, Bakteeva, Ngoga and Mugabukomeye. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

This article is part of the Research Topic

Ecotourism Models: Identifying Contributions to Conservation and Community

Navigating the Balance Between Revenue Generation and Conservation at a Cham Living Sacred Heritage Site: Priestly Views and Challenges

- Open Access

- First Online: 13 October 2023

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Quang Dai Tuyen 4

Part of the book series: Global Vietnam: Across Time, Space and Community ((GVATSC))

783 Accesses

Tourism Benefit-Sharing (TBS) has gained significant attention in the past two decades as a means of providing economic opportunities and preserving natural protected areas (PAs) and cultural heritage sites globally.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Introduction

Tourism Benefit-Sharing (TBS) has gained significant attention in the past two decades as a means of providing economic opportunities and preserving natural protected areas (PAs) and cultural heritage sites globally (Akbar & Yang, 2021 ; Xu et al., 2009 ). TBS fosters relationships between local communities and authorities, providing an important factor in creating sustainable destinations and contributing to the 17 SDGs (Carius & Job, 2019 ; Imanishimwe et al., 2018 ). Effective benefit-sharing, as described in this study, involves local authorities fairly distributing the economic benefits from tourism revenue to Indigenous communities, which enhances their social and economic environment and encourages mutual relationships (Balmford et al., 2009 ).

Revenue generated from tourism development of PAs has the potential to provide economic benefits, introduce local culture, promote economic diversification, improve the quality of social services, and enhance local infrastructure (Melita & Mendlinger, 2013 ; Tumusiime & Vedeld, 2012 ). However, despite extensive research on TBS, debates on the most effective forms of PA conservation persist (Archabald & Naughton-Treves, 2001 ; Queiros & Mearns, 2019 ; Spenceley et al., 2017 ). Local communities play a crucial role in identifying and evaluating the value of TBS, despite varying stakeholder perceptions (Tumusiime & Vedeld, 2012 ). Hence, there is a pressing need for win–win TBS policies that maintain the sustainable development of PAs (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2010 ; Mukanjari et al., 2013 ; Spenceley et al., 2017 ; Tumusiime & Vedeld, 2012 ).

TBS has been widely studied in the context of national parks around the world (Makame & Boon, 2017 ; Munanura et al., 2016 ), but less research has focused on TBS at cultural heritage sites, particularly living heritage sites, which play a crucial role in preserving the cultural heritage of Indigenous communities. Literature suggests that TBS is an important way to explore the economic impacts of tourism on local communities (Mbaiwa & Stronza, 2010 ; Xu et al., 2009 ). However, most studies have been conducted in African countries, leaving other regions, such as Southeast Asian countries, largely overlooked. This research fills this gap by focusing on TBS in the context of ethnic and cultural heritage in Vietnam.

Studies on TBS have investigated perspectives of various stakeholders, including authorities, PA management boards, and local communities (Bruyere et al., 2009 ; Carius & Job, 2019 ; MacKenzie, 2012 ; Weisse & Ross, 2017 ). However, in-depth studies on different target groups within the local community, especially those engaged in conservation of living heritage, seem to be scarce. Moreover, previous studies have emphasized tourism revenue allocation but have not clarified the distribution of tourism revenue among host communities and who in the community should receive it (Mbaiwa & Stronza, 2010 ; Snyman & Bricker, 2019 ). In the Vietnamese context, there have been studies on the living heritage of the Kinh majority group, such as Huong Pham’s ( 2015 ) examination of the economic impact of tourism on local people in Hoi An Ancient Town. However, the living heritage of minority communities has not received the same level of attention.

Tourism plays a significant role in driving Vietnam’s transformation into a developed nation (Saltiel, 2014 ). One of the key components of this growth is the promotion and preservation of ethnic minority heritage, which attracts a significant number of tourists to the country (Lask & Herold, 2004 ; Salemink, 2013 ; Saltiel, 2014 ; Truong, 2013 ). The government of Vietnam has recognized the importance of ethnic minority heritage and has issued several policies and guidelines aimed at promoting socio-cultural and social development for ethnic minorities, including the Cham people of Ninh Thuận (Lask & Herold, 2004 ). The preservation of the Cham cultural heritage is crucial not only for the promotion of tourism but also for the overall development of the country and its people.

As the focus of this study, the Cham people in Ninh Thuận boast an abundant cultural heritage, including over 70 festivals and ceremonies that are still performed annually with the participation of the Cham community and guidance from religious dignitaries (Sakaya, 2003 ). The Cham’s traditional approaches to the stewardship of sacred sites have been officially recognized and promoted by the government since 2012, with representatives from the Ahier Cham community serving as consultants on cultural and religious issues concerning the Cham community.

This rich cultural heritage, particularly the temple-tower architecture system found throughout the Central region and in Ninh Thuận Province, has become a major tourist attraction and product in Vietnam. In 2019, Ninh Thuận welcomed 2.35 million visitors, a 7.3% increase from the previous year, with 100,000 being international arrivals (an annual increase of 25%) and 2.25 million being domestic arrivals (an annual increase of 6.6%) (Sở VH-TT-DL, 2020 ).

While the rise in tourism has brought positive economic benefits to the region, it has also led to concerns over the allocation of economic benefits from the Cham cultural heritage sites and the satisfaction of the Cham people as the owners and guardians of this cultural heritage. This chapter seeks to address these concerns by exploring the challenges faced by Cham dignitaries in maintaining their cultural heritage through TBS, and examining their perspectives on TBS and its impact on their cultural heritage. This study aims to contribute to the understanding of how equitable TBS can be developed at a living heritage site, where the financial benefits from the commodification of minority culture can be used to support local communities and the custodians of Indigenous heritage.

The contribution of this research is substantial in several key aspects. Firstly, it brings to light the difficulties faced by Cham dignitaries in safeguarding the cultural heritage of the Cham community in Ninh Thuận. Secondly, it explores the views of the Cham dignitaries on TBS and its impact on their cultural heritage. Additionally, it provides an in-depth understanding of the distribution of economic benefits from Cham cultural heritage sites and the satisfaction of the Cham community with TBS. Furthermore, this research contributes to the broader knowledge base on the significance of TBS in the preservation and promotion of cultural heritage. The findings can serve as a useful reference for policymakers and practitioners when developing equitable TBS programs, especially in the context of living heritage sites. The study emphasizes the importance of inclusive and culturally appropriate TBS programs that prioritize the involvement and benefit of local communities, including Indigenous people, by taking into account the challenges faced by the Cham dignitaries and their perspectives. Furthermore, the insights gained from this study can also inform the creation of sustainable and socially responsible cultural tourism programs. By highlighting the challenges faced by the Cham dignitaries, this research can steer future research in the field of cultural heritage preservation and promote best practices for equitable TBS. Overall, this study provides valuable insights into the challenges and opportunities faced by the Cham community in preserving their cultural heritage and the role of TBS in supporting these efforts.

Traditional Custodianship and Cultural Heritage Preservation

The preservation of cultural heritage has been a topic of great concern in the contemporary era. Western heritage management practices have widely impacted many nations, and although these approaches have had a significant impact, they have often neglected the vital role that traditional custodianship systems play in protecting and preserving a community’s heritage in the long term. Despite the recognition of the crucial role that traditional custodianship systems play in heritage management, these systems have often been overlooked in regions such as Asia and Africa (Chirikure et al., 2010 ; Ndoro & Wijesuriya, 2015 ).

However, this perspective has been challenged by several case studies in Africa that demonstrate the significance of traditional custodianship systems in heritage management (Abungu, 2015 ; Waterton, 2010 ). These studies highlight the importance of incorporating traditional management systems into the management of cultural heritage and have been recognized by UNESCO ( 2013 ) as a key component in the management of cultural heritage.

Unfortunately, some researchers have found that there is a lack of consultation with local communities in the management of cultural heritage in Africa in practice, as these communities are not considered to be conservation experts (Abungu, 2015 ; Waterton, 2010 ). This overlooks the vital role that traditional custodianship systems play in protecting and managing cultural heritage over the long term (Chirikure et al., 2010 ; Ndoro & Wijesuriya, 2015 ). However, there is a growing recognition of the significance of traditional custodianship systems in managing cultural heritage, and their role is increasingly being acknowledged and integrated into heritage management practices (Abungu, 2015 ; UNESCO, 2013 ).

To effectively preserve cultural heritage, it is crucial to recognize the value of traditional custodianship systems and to involve local communities in the management and protection of their cultural heritage (Chirikure et al., 2010 ; Ndoro & Wijesuriya, 2015 ). By doing so, we can ensure that cultural heritage is not only preserved, but also sustained and passed down from generation to generation (Abungu, 2015 ; UNESCO, 2013 ). The integration of traditional management systems into heritage management practices will also ensure that the heritage reflects the values and traditions of the local communities and that their voices are heard in the decision-making process (Weise, 2013 ). In short, the recognition of the importance of traditional custodianship systems and the involvement of local communities in the management of cultural heritage are critical components in ensuring the preservation and sustainability of cultural heritage (Abungu, 2015 ; Chirikure et al., 2010 ; Ndoro & Wijesuriya, 2015 ; UNESCO, 2013 ; Weise, 2013 ).

Traditional custodianship systems play a key role in the preservation and management of cultural heritage within communities. These systems are often rooted in customary laws that govern the use of sacred sites and protect them from violations (Abungu & Githitho, 2012 ; Harris, 1991 ; Shen et al., 2012 ). The regulations and principles established by these traditional systems help to minimize negative impacts on heritage sites and are a significant aspect of the local community’s connection to the landscape and its resources (Smith & Turk, 2013 ). However, the significance of traditional custodianship systems is often disregarded in heritage conservation and development, leading to the creation of a form of heritage that goes against local views and traditions, thereby reducing the cultural significance of the heritage being preserved (Byrne, 2012 ). This is due in part to the fact that these systems are often overlooked in heritage management practices (Bwasiri, 2011 ).

To address this issue, scholars have recommended integrating local customary systems within Western conservation models as the most effective approach to cultural heritage management (Bwasiri, 2011 ; Smith & Turk, 2013 ). This approach enables the exploration of the social concerns and needs of the local community, which is a crucial consideration, particularly in the case of the Cham community studied in this research. By considering the perspectives and needs of the Cham community, the government can effectively manage the Cham temples for the benefit of the Cham people, while preserving the cultural heritage and its traditional values.

The preservation of cultural heritage requires a holistic approach that takes into account the perspectives and needs of the local community who are connected to the heritage site (Weise, 2013 ). A top-down approach to heritage management, such as limiting access to cultural heritage resources for local communities, can have negative consequences for their livelihoods and traditional ways of life (Fletcher et al., 2007 ; Miura, 2005 ). Miura ( 2005 ) suggests that heritage sites should be protected by incorporating the values held by the living population, as they are the ones who will be responsible for passing down these values to future generations.

Moreover, imposing heritage management without taking into account the desires of the community and providing a functional and sustainable system will result in the loss of authenticity, as argued by Weise ( 2013 ). In order to preserve cultural heritage, it is necessary to consider both the tangible and intangible aspects of heritage, as well as the social concerns of the local community. Decision-making in heritage management should be guided by the living heritage and the perspectives of the community who holds the heritage, as this will ensure that the heritage is maintained in a culturally appropriate and sustainable manner (Weise, 2013 ).

Tourism Benefit-Sharing: The Importance of Involving Local Communities

The literature review section on Tourism Benefit-Sharing (TBS) has focused on exploring the relationship between protected areas (PAs) that have become tourism destinations and the allocation of benefits to local communities. TBS has emerged as a crucial component of sustainable tourism development in protected areas, providing finance for conservation activities and infrastructure development (Mbaiwa & Stronza, 2010 ; Spenceley et al., 2017 ). In recent years, scholars have become interested in integrating heritage conservation and tourism development (Munanura et al., 2016 ), recognizing that benefits derived from tourism can bring tangible and intangible benefits to local communities.

Tangible benefits include the creation of jobs, direct income, and improved infrastructure, while intangible benefits include capacity building, skills training, and cultural development (Spenceley et al., 2017 ). The key to effective TBS is a mutual understanding between the government and local communities, where the government provides welfare opportunities and the local communities maintain conservation and sustainable development (Bebbington, 1999 ; Makame & Boon, 2017 ; Spenceley et al., 2017 ). This relationship can be further strengthened by providing social and cultural capital, as well as living support and substantive opportunities to encourage community engagement in heritage conservation (Bebbington, 1999 ; Gautam, 2009 ). Local communities should also have equal social and economic support and opportunities to achieve sustainable livelihoods (Norton & Foster, 2001 ; Spenceley et al., 2017 ).

However, there have been cases where TBS has not been fair to local communities, with only a small part of tourism revenue being shared with a small number of direct beneficiaries in the community (Schnegg & Kiaka, 2018 ). Benefits are often leaked externally to foreign travel agencies, provincial or central businesses, or other organizations (Ahebwa et al., 2012 ; Sandbrook, 2010 ). To ensure that economic benefits are directly shared with the local community, it is important to establish access rights and sharing mechanisms for the host community (Kiss, 2004 ; Lapeyre, 2011 ; Wunder, 2000 ). For example, in Rwanda, 5% of the annual income from tourism revenue is dedicated to promoting local community livelihoods, demonstrating that TBS can improve lives and sustainably preserve heritage (Munanura et al., 2016 ).

The concept of Tourism-based Sustainability (TBS) has been a topic of interest among scholars and researchers due to its complexity and difficulty in implementation. This is highlighted in the studies conducted by Adams et al. ( 2004 ) and Snyman and Bricker ( 2019 ) which indicate the multifaceted nature of TBS. To address the challenges of TBS, local authorities must adopt a comprehensive approach that considers the interests of all stakeholders (Benjaminsen & Svarstad, 2010 ). One way of enhancing the success of TBS is through community empowerment. This involves encouraging communities to take an active role in tourism activities, such as through joint ventures or other cooperative management models (Baghai et al., 2018 ). This is further emphasized by Heslinga et al. ( 2019 ) who stress the significance of community empowerment in overcoming participation barriers in TBS.

Furthermore, a study by Li ( 2006 ) on community participation in decision-making in Sichuan, China found that communities still benefit from tourism development even when their participation in decision-making is weak. This highlights the importance of community involvement in TBS, as it not only benefits the community but also contributes to the overall success of TBS initiatives. Li ( 2006 ) argues that community participation is not a final goal in itself, but rather a means to achieving community involvement in tourism activities.

The literature on Tourism-based Sustainability (TBS) has mainly focused on collaborations between Indigenous communities and governments (Chirikure et al., 2010 ; Smith & Waterton, 2009 ; Waterton, 2015 ) and Indigenous custodian systems (Jones, 2007 ; Ndoro, 2004 ; Sharma, 2013 ; Smith & Turk, 2013 ). However, despite this extensive research, the social conditions of the Indigenous custodians, who play a central role in Indigenous custodianship, have often been overlooked. This is particularly problematic in the case of the Ahiér priests, who serve as Cham custodians, and are vital for effectively managing living Cham heritage sites to achieve sustainability. The Ahiér priests bring the Po Klaong Girai temple and Cham culture to life.

This research highlights the importance of understanding the social conditions of Cham custodians in the context of TBS. Snyman and Bricker ( 2019 ) argue that identifying the needs and problems of the community’s institutional system is necessary to comprehend the effectiveness of TBS. Moreover, MacKenzie ( 2012 ) and Strickland-Munro and Moore ( 2013 ) emphasize that understanding the needs of Indigenous communities and stakeholders in TBS is a critical foundation for achieving sustainable development goals.

In conclusion, the literature highlights the importance of considering the social conditions of Indigenous custodians in TBS. It is necessary to understand the community’s institutional system and the needs of Indigenous communities and stakeholders for effective TBS and sustainable development.

Study Background and Context

The Cham are a distinct ethnic group in Vietnam, originating from the central region and known for their long-standing history and rich cultural traditions. Their contributions to Vietnamese culture are especially evident in their beliefs and customs, which are reflected in traditional festivals and ancient beliefs.

The Cham communities are still predominantly concentrated in certain provinces in South Central and Southern Vietnam, with the oldest settlements located in Ninh Thuận Province. According to the General Statistics Office, there were 178,948 Cham people in Vietnam in 2019, with 82,532 residing in Ninh Thuận Province alone. The Cham culture is alive and vibrant in Ninh Thuận, with vibrant colors evident in writing, costumes, architectural art, sculptures, and traditional crafts. The preservation of Cham matriarchal customs is noteworthy (Biên et al., 1989 , 1991 ; Sakaya, 2003 ), and many forms of Cham cultural heritage have been recognized by the Vietnamese state (Table 9.1 ).