clock This article was published more than 3 years ago

Jan Morris, artful travel writer who broke many boundaries, dies at 94

As a young reporter, Jan Morris was on the mountainside, at 22,000 feet, when the first expedition in history reached the top of Mount Everest. She reported on wars and revolutions around the globe, published dozens of elegant books exploring far-flung places and times and was regarded as perhaps the greatest travel writer of her time.

Yet the most remarkable journey of her life was across a private border, when she cast off her earlier identity as James Morris and became Jan Morris.

A writer of extraordinary range and productivity, and one of the world’s first well-known transgender public figures, Ms. Morris was 94 when she died Nov. 20 at a hospital in the Welsh town of Pwllheli. Her son Twm Morys announced the death in a statement but did not state the cause.

Jan Morris spent her first 45 years as James Morris, who had been a British cavalry officer, a World War II veteran and a dashing reporter renowned for international adventures and evocative writing.

“On the face of things,” a onetime colleague, David Holden, wrote in 1974, “a less likely candidate for a sex change than James Morris would have been hard to imagine. His whole career and reputation had created an aura of glamorous and successful masculinity.”

In the 1940s, James Morris lived on the Nile on the houseboat of British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. In 1953, never having climbed a mountain before, James joined the expedition of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay and came within 7,000 feet of the summit of Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak. Scrambling back down, James delivered the news that Everest had been conquered for the first time in history. The Times of London printed the story on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

“I went up an unknown,” Ms. Morris told the New York Times in 1997, “and came down the most famous journalist in the world.”

Constantly on the move, James Morris reported from Israel, Algeria, South Africa and Japan, primarily for British newspapers and magazines, published books and was praised by New York Times critic Orville Prescott as a “poet and a phrase-maker with a fine flair for the beauties of the English language.”

James Morris covered the Moscow show trial of U.S. spy plane pilot Francis Gary Powers and the trial in Jerusalem of unrepentant Nazi henchman Adolf Eichmann. In Cuba, James interviewed the charismatic revolutionary Che Guevara and in a 1960 dispatch published in the New York Times offered a grim assessment of what the future would hold for the country under Fidel Castro. ”

“It is a strikingly immature regime — not just in age but in style and judgment too. The rulers of Havana reduce all things to simple right or wrong, East or West, in or out, yours or ours. There still is good in many of their notions, a surviving streak of idealism, a genuine quality of young inspiration. But there is little subtlety, no experience, and scarcely a jot of that prime political commodity, irony.”

In 1960, James Morris published the best-selling “Venice” (called “The World of Venice” in the United States), creating a distinctive style of travel writing, a literary dreamscape evoking past and present at once, as sensory impressions and a poignant awareness of what some called the “psychology of place” were threaded into an elegant, flowing prose.

Venice — for centuries an independent republic before it became part of Italy — “was something unique among the nations, half eastern, half western, half land, half sea, poised between Rome and Byzantium, between Christianity and Islam, one foot in Europe, the other paddling in the pearls of Asia. She . . . even had her own calendar, in which the year began on March 1st, and the days began in the evening.”

Other books followed, about New York, Britain, South America and Spain, as well as an ambitious three-volume history of the British Empire that was so authoritatively written that critics were reminded of Edward Gibbon’s monumental 18th-century chronicle of ancient Rome.

James Morris had public acclaim and a seemingly contented family life as the married father of four children — but there remained a central, inescapable fact: a misaligned gender identity, “a life distorted.”

“I was three or perhaps four years old,” Jan Morris wrote in her first book under that name, the autobiographical “Conundrum” (1974), “when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl. I remember the moment well” — sitting under the piano, while her mother played Sibelius — “and it is the earliest memory of my life.”

Before marrying Elizabeth Tuckniss in 1949, James Morris explained this sense of inner conflict, telling her that “each year my every instinct seemed to become more feminine, my entombment within the male physique more terrible to me.”

James Morris began hormone treatments in 1964 and consulted with Harry Benjamin , an American physician and the author of “The Transsexual Phenomenon” (1966). In 1972, James went to Casablanca for transition surgery, choosing a doctor experienced in the procedure.

Two weeks later, Jan Morris flew back to England, where she was greeted by Elizabeth. Under British law at the time, they had to obtain a divorce because same-sex couples were not permitted to marry. Still, they continued to live together.

“To me gender is not physical at all, but is altogether insubstantial,” Ms. Morris wrote in “Conundrum,” which became an international best seller. “It is the essentialness of oneself, the psyche, the fragment of unity. Male and female are sex, masculine and feminine are gender, and though the conceptions obviously overlap, they are far from synonymous.”

Many readers admired Ms. Morris’s revelatory candor, but others were confused or hostile. In Esquire magazine, Nora Ephron disparaged “Conundrum” as “a mawkish and embarrassing book. . . . Jan Morris is perfectly awful at being a woman; what she has become instead is exactly what James Morris wanted to become those many years ago. A girl. And worse, a 47-year-old girl.”

In any case, Ms. Morris continued with her writing life much as before, only wearing skirts, necklaces, a nimbus of graying hair and a perpetual smile.

She completed the final volume of the British Empire trilogy and continued to wander the globe, writing for Rolling Stone and other publications. The books seem to pour out of her, often with simple titles such as “Travels,” “Journeys,” “Destinations” and “Among the Cities.”

She became almost a revered figure, considered a founder of modern travel writing, even though she resisted the title.

“The reason why I don’t regard myself as a travel writer is that the books have never tried to tell somebody what a city is like,” she told the Independent in 2001. “All I do is say how I’ve felt about it, how it impinged on my sensibility.”

Ms. Morris was often asked which city in the world, out of the hundreds she knew, was her favorite. She invariably named Manhattan and Venice, both of which she visited every year.

But she also had an abiding attachment to Trieste, a somewhat eccentric port city in northeastern Italy. Ms. Morris first saw Trieste in 1945, then returned periodically over the years before publishing in 2001 what she considered perhaps her finest travel book, “Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere.”

“The nostalgia that I felt here 50 years ago was, I realize now, nostalgia not for a lost Europe, but for a Europe that never was, and has yet to be,” she wrote. “But we can still hope and try, and be grateful that we are where we are, in this ever-marvelous and fateful corner of the world.”

James Humphry Morris was born Oct. 2, 1926, in Clevedon, England.

At 17, James Morris joined the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers , a storied British cavalry unit, and served in Italy and the Middle East during World War II. James later worked for a news agency in Cairo, then returned to Britain to study at the University of Oxford, graduating in 1951.

After working for the Times of London for several years, James joined what was then the Manchester Guardian in 1956 as “wandering correspondent,” winning a George Polk Award for journalism in 1960. A year later, James became a freelance writer and received a master’s degree in English literature from Oxford.

It was in Oxford where James Morris made the first tentative steps toward becoming Jan, going out in public wearing dresses and makeup, years before athletes Renée Richards and Caitlyn Jenner were heralded as transgender pioneers.

In 2008, Ms. Morris and Elizabeth Tuckniss Morris were united in a civil union.

“I made my marriage vows 59 years ago and still have them,” Elizabeth Morris told Britain’s Evening Standard. “We are back together again officially. After Jan had a sex change we had to divorce. So there we were. It did not make any difference to me. We still had our family. We just carried on.”

They settled in the Welsh village of Llanystumdwy, with one of their sons living next door. The couple arranged for a headstone with an inscription in Welsh and English: “Here are two friends, at the end of one life.”

In addition to Elizabeth Morris and their son, Twm Morys, survivors include three other children. Another child, a daughter, died in infancy.

If anything, Jan Morris was a more productive writer than James had been. She often published two or three books a year, and more than 45 in all. Besides her accounts of travel, history and autobiography, she wrote two novels and biographical studies of Abraham Lincoln and British admiral John Fisher.

In 2018, she published “Battleship Yamato,” about an ill-fated Japanese warship that was sunk in 1945. It was believed to be one of the last books about World War II written by a veteran of the war. She continued to publish essays about her life in Wales, her memories and what she called the “tangled web” of her life until shortly before her death.

“I spent half my life traveling in foreign places,” Ms. Morris wrote in “Conundrum.” “I did it because I liked it, and to earn a living, and I have only lately recognized that incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.”

Read more Washington Post obituaries

Jan Myrdal, radical and rebellious Swedish writer, dies at 93

Diane di Prima, feminist poet of the Beat Generation, dies at 86

Pete Hamill, journalist, novelist and tabloid poet of New York, dies at 85

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Author Interviews

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Remembering Travel Writer And Memoirist Jan Morris

Terry Gross

Morris, who died Nov. 20, transitioned to female in 1972 when she was 46. She later reflected on gender in her memoir, Conundrum . Originally broadcast in 1989.

Copyright © 2020 NPR. All rights reserved. Visit our website terms of use and permissions pages at www.npr.org for further information.

NPR transcripts are created on a rush deadline by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its final form and may be updated or revised in the future. Accuracy and availability may vary. The authoritative record of NPR’s programming is the audio record.

National Geographic content straight to your inbox—sign up for our popular newsletters here

Why the mystique of Wales gave strength to a legendary writer

With Welsh legends and landscapes as her muse, Jan Morris circled the globe—and reinvented travel writing.

Celebrated travel writer Jan Morris, who died November 20, 2020, lived and worked in the scenic Nant Gwynant valley in westernWales.

She was at ease in the world, but she was never more herself than when at home in Wales. Author and journalist Jan Morris, who died last week at 94, embraced Wales as her physical, intellectual, and spiritual foundation. “I am emotionally in thrall to Welshness,” she said.

She loved its rugged mountains, the spring-green hills where sheep grazed, even the gloomy weather, which was ideal for writing by the fireplace. In Wales , Morris saw an ancient nation that retained its indomitable essence. The endurance of identity was among her great themes.

Morris would often take visitors to lunch at a handsome, ivy-cloaked climbers’ lodge in northwest Wales. The lodge is a converted 200-year-old farmhouse called Pen-Y-Gwryd . One could say it was here, in 1953, that the first successful ascent of Mount Everest began, with Morris joining training climbs up nearby Mount Snowdon.

Late in life, Welsh historian, author, and travel writer Jan Morris is shown near her home in Wales.

Morris was a 26-year-old reporter for the Times of London , the sole journalist on the British expedition led by Colonel John Hunt that was the first to reach the summit of the world’s highest mountain.

( Related: Hike the Wales Way to see the best of this ancient land. )

On May 29, 1953, when Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary reached the summit, Morris hiked thousands of vertical feet above Everest base camp to be the first to get the news. Upon learning that Hillary and Tenzing had succeeded, Morris raced back to base camp, roped up with another climber, then hustled down the mountain and sent an encoded message back to London . The news reached the British on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, giving the nation another reason to celebrate.

Morris later described the Everest scoop as the first and only of her career, which spun her out from Wales to travel the globe, filing lyrical, impressionist essays from Venice , Sydney , New York , Hong Kong . But she’d always return to Wales.

Finding a home and kinship

Born in 1926 to a Welsh father and English mother in Somerset, England—140 miles west of London and just across Bristol Bay from Cardiff, Wales’s capital—Morris loved Wales and wanted to share it.

The Welsh name for the country is Cymru, a word rooted in “kinship.” This appealed greatly to Morris, as did the defiantly proud red dragon that commands the national flag. Despite seven centuries of domination by England, the region of northern Wales that Morris called home remains irrefutably Welsh.

The Welsh language, one of the oldest in Europe, is still spoken widely there, and national pride is so strong that visitors can be initially suspect. Yet the moment outsiders show even a hint of sympathy for the Welsh cause or appreciation of the place, they’re typically welcomed with open arms.

“I live, though, in a Wales of my own, a Wales in the mind, grand with high memories, poignant with melancholy,” Morris writes in her 2002 book, A Writer’s House in Wales , published by National Geographic. Although Morris fiercely supported Wales and all it stands for, she recognized that she had adopted her country; she wasn’t wholly of it. The weathervane gracing her home in Llanystumdwy on the Llŷn Peninsula symbolizes her dual Welsh and English ancestry: E and W mark east and west; G and D stand for gogledd and de , the Welsh words for north and south.

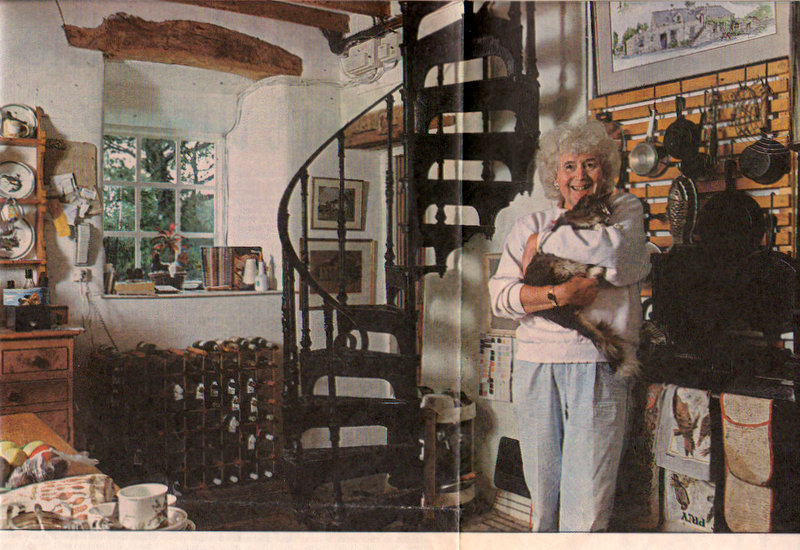

Morris described her small home in Trefan Morys as “a summation, a metaphor, a paradigm, a microcosm, an exemplar, a multum in parvo, a demonstration, a solidification, an essence, a regular epitome of all that I love about my country.” And she opened her doors to countless travelers over the decades.

A man and his dogs rest at the viewpoint from Castell Dinas Bran, a medieval castle far above the Dee Valley in Wales.

Beddgelert is a pretty Welsh village known for the legend of a faithful dog by the same name.

“She had a choice, being half English and half Welsh. She chose Wales,” says photographer Jim Richardson, recalling lunch with Morris in the Smoke Room at Pen-Y-Gwryd. The lodge, festooned with ropes and oxygen tanks and boots used on the Everest expedition, was the site of many reunions.

“But most revealing was her ability to find the richness in this simple Welsh countryside,” says Richardson. “As we drove up the Nant Gwynant valley past Mount Snowdon, she was as likely to point with pride to the sheep as she was to the mountain; she did not need epic places in order to see epic things.” Morris told the story of racing down Everest, “as if she were sitting around with some Welsh farmers talking about sheep shearing. She laughed. It was fun, this world of hers.”

Wales, for Morris, was both a place to discover and a place to define. “You can see from the way she writes about Wales that her heart and soul is in it,” said author Paul Theroux in an email after Morris died. “In a word, Jan was passionate about Wales—the land, people, the language—and she was subtle yet forceful in writing about it, to the point of being a Welsh nationalist, not a popular role in Great Britain.”

Forging an identity in an ancient land

Morris was raised as a boy, but “was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl,” she writes in Conundrum . Morris began taking hormones in the mid-1960s and had gender confirmation surgery in Casablanca in 1972, at age 46.

In her view the world made too big of a fuss over this—she lamented her obituary would read: “Sex change author dies.” Yet it was another pioneering journey. “I haven’t gone from one sex to the other,” she told the Times of London in 2018. “I’m both.”

(Related: See how these 21 female explorers changed the world.)

The ruins of the medieval Castell Dinas Bran tower above the Dee Valley and the bustling town of Llangollen. The rugged, foreboding pinnacle was an ideal spot for a castle, but the native Welsh princes who erected it only occupied the site for a few decades.

As an explorer, an author, and most of all as a human being, Morris contained multitudes and didn’t fear contradictions. But she remained steadfastly Welsh.

“I think it was very important for Jan to be Welsh and always to define herself as such,” says author Pico Iyer. Morris’ writing inspired him to envision a life as a traveling journalist. “She was our master impressionist, the greatest portraitist of place we’ll ever read: She gathered a thousand details and pieces of history and perceptions and put them together in a mosaic that caught the soul of a place,” Iyer says.

“Though such a lover of cities, she chose to live in relative isolation in the country; her Welshness allowed her to cast something of an outsider’s eye on all that London sent around the world in the days of Empire, and to feel for the oppressed, the marginal. Solitary, in her own domain, not hostage to England and its limitations, Jan’s life in Wales seemed in many ways a model of her position in the world.”

A diligent and erudite scholar known for her seminal Pax Britannica trilogy about the rise and fall of the British Empire, Morris conveyed a sense of fun in her writing. In keeping with her Welsh roots, she laughed easily and brought a lighthearted tone to much of her work. She loved language and enjoyed using words, such as “kerfuffle,” that may have caused some critics to take her work less seriously than they should have.

Another favorite word was hiraeth , Welsh for an ineffable longing. In the end, Jan’s world was all about kindness and kinship, and she fostered a community of open-hearted travelers.

“There are people everywhere who form a Fourth World, or a diaspora of their own,” she writes in her elegiac book, Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere . “They share with each other… the common values of humour and understanding. When you are among them you know you will not be mocked or resented … they suffer fools if not gladly, at least sympathetically. They laugh easily. They are easily grateful. They are never mean. … They are exiles in their own communities, because they are always in a minority, but they form a mighty nation, if they only knew it.”

Capturing the magic of her homeland

This concept of exile is deeply rooted in Morris’ experience of Wales. It’s not just what her chosen country transmitted to her, but what she projected onto the place. Morris often said that she couldn’t make a sharp distinction between fact and fiction: While her reporting was rigorously accurate and thorough, her writing was typically a synthesis of her imagination and her experience.

Llanddwyn Island sits of the southwest coast of Anglesey in North Wales. To reach it, you must cross a spit of sand at low tide or take a boat.

“It is a different thing for [my son] Twm,” who grew up in Wales, Morris told the Guardian , last year. “I don’t have his instinct for Welshness. With him it is more basic, it comes out of the soil.”

In her 1984 book, The Matter of Wales: Epic Views of a Small Country , Morris writes that the Welsh “never altogether abandoned their perennial vision of a golden age, an age at once lost and still to come—a vision of another country almost, somewhere beyond time.”

( Related: Why does Wales have the most castles of any country in Europe? )

At her 90th birthday party in 2016, Morris said that although her travels have taken her to many exotic locations, her corner of Wales has been her “chief delight,” recalls Paul Clements, author of Jan Morris: Around the World in Eighty Years , a collection of tributes by noted authors. “What I have done for Wales,” Morris said at her party, “is infinitesimal compared to what Wales has done for me.”

When I interviewed Morris for my book, A Sense of Place , she noted that for centuries Anglo civilization has been “pressing on Wales, and yet the little country seems to have survived and kept its soul and spirit. I like the nature of the Welsh civilization, which is basically very kind; it’s not very ambitious or thrusting. It’s based upon things like poetry and music, which are still very deeply rooted in this culture.”

Trefan Morys, the home Morris shared with her lifelong partner Elizabeth Tuckniss Morris, who survives her, sits just above the River Dwyfor. A year from now her ashes will be spread on an island in this stream, said Morris’s son, Twm Morys, the renowned Welsh poet and author. The islet is called Ynys Llyn Allt y Widdan, which means the “Island of the Pool of the Slope of the Sorceress.”

How fitting. For Jan Morris was, in a way, the sorceress of Wales. She conjured a sympathetic and uplifting vision of her beloved adopted country, and through eloquence and determination transmuted it into her personal reality. Through a lens of generosity and imagination, Morris saw Wales as no one has before, and the world is richer for it.

Related Topics

- MOUNTAINEERS

You May Also Like

Why visit Annecy, gateway to the shores and summits of the French Alps

Sleeper trains, silent nights and wee drams on a wild walk in Scotland

For hungry minds.

What you need to know about volcano tourism in Iceland

How to plan the ultimate adventure in the Himalayas, from beginners' hikes to Everest base camp

Max Leonard treks back in time along the mountainous Italian-Austrian border

Photo story: horseback adventures on the gaucho trail through southern Patagonia

Meet the British mountaineer chasing small adventures after a life-changing stroke

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Gory Details

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Manage Your Subscription

- Give a Gift Subscription

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Culture + Design

The Extraordinary Life of Jan Morris, Travel Writer and Pioneering Trans Person

In her classic travel narratives, Morris captured the essence of the world’s great cities—and the complexities of her own life.

In her masterful 2002 book, Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere , Jan Morris writes of how the northern Italian city always evoked in her a vague but powerful yearning. "My acquaintance with the city spans the whole of my adult life, but like my life it still gives me a waiting feeling, as if something big but unspecified is always about to happen," she writes.

A twilight book, published the year Morris turned 75, it is about the port city of the former Habsburg Empire and how the city's essence lies in its long and layered history as a generally felicitous meeting of cultures and peoples, languages and empires. But it is also a book about returning to places we knew in the past, and how travel lets us take the measure of ourselves as well as of our destinations. "The allure of lost consequence and faded power is seducing me, the passing of time, the passing of friends, the scrapping of great ships!" she writes of the city. "It is as though I have been taken, for a brief sententious glimpse, out of time to nowhere."

That description is pure Morris. So is the exclamation mark. There's nothing mournful or lugubrious here, but exuberance, vivacity, a piercing clarity of vision that characterizes all of Morris' work. I also can't help but read Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere as somewhat autobiographical—an account of a city that, like Morris herself, is a palimpsest of lives, that contains multitudes and layers and does so with dignity, clarity and self-awareness.

Morris died in late November at age 94 after an extraordinary life. Born James Morris, she (then he) sang in the boys' choir at Christ Church, Oxford, served in the British Army, scaled two-thirds of Mount Everest to report on Sir Edmund Hillary's triumphant ascent to the summit in 1953, became a foreign correspondent who broke news of French involvement in the Suez crisis in 1956, wrote dozens of brilliant works of history and travel reportage—and then, after years of hormone therapy, underwent a change of sex in Casablanca in 1972, emerging as Jan.

Her 1974 autobiography, Conundrum , begins: "I was three or perhaps four years old when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl." The book is notable for its matter-of-fact lucidity. "I never did think that my own conundrum was a matter either of science or of social convention," Morris wrote in a 2001 introduction to the book's reissue. "What was important was the liberty of us all to live as we wished to live, to love however we wanted to love, and to know ourselves, however peculiar, disconcerting or unclassifiable, at one with the gods and angels."

That same spirit of self-knowledge informs the works in which Morris captured the spirit of a place with a few seemingly effortless brush strokes. Deeply learned, Morris was more a student of history than a teacher—always an enthusiast, never a pedant. I particularly love the dispatches she wrote for Rolling Stone between 1974 and 1979—socio-anthropological portraits of cities. (They were collected in a 1980 volume, Destinations .)

On Johannesburg in 1976, after the start of the township riots that would years later help bring down the Apartheid regime: "There it stands ringed by its yellow mine dumps, like stacks of its own excreta, the richest city in Africa but altogether without responsibility." And Istanbul in 1978: "There can never be a fresh start in Istanbul. It is all too late. Its successive pasts are ineradicable and inescapable."

Related : 2 Transgender Travelers on Exploring the U.S. and the World, Episode 15 of Travel + Leisure's New Podcast

Morris was fascinated by what makes cities work—their geographies, the source of their wealth. " London is hard as nails, and it is opportunism that has carried this city of moneymakers so brilliantly through revolution and holocaust, blitz and slump, in and out of empire, and through countless such periods of uncertainty as seem to blunt its assurance now," she wrote in 1978. In 1976 she visited Los Angeles, stayed in the Chateau Marmont, and examined the city's celebrity industry. Of New York in 1979, Morris observed: "Analysis, I sometimes think, is the principal occupation of Manhattan—analysis of trends, analysis of options, analysis of style, analysis of statistics, analysis above all of self."

Although Morris is more often generous of spirit, her dispatch from Washington, D.C. in 1976 is cutting. "Nowhere in the world, I think, do people take themselves more seriously than they do in Washington, or seem so indifferent to other perceptions than their own," she wrote. In her visits to all three American metropolises, she was struck by their peculiar combination of global power and extreme provincialism.

In this era of Instagram stories and this pandemic season of armchair travels , I have found great pleasure in reading Morris' dispatches. They offer rich, complex pictures, not individual pixels. But it's still her Trieste book that hits me deepest. It is a vision of a city fully aware of itself and its historical obsolescence, yet that nevertheless endures. "To my mind this is an existentialist sort of place," she writes. "Its purpose is to be itself." So was Morris'. Her work lives on.

Related Articles

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Jan Morris: She sensed she was ‘at the very end of things’. What a life it was …

In her final interview just before the first lockdown, the renowned travel writer spoke cheerfully of her last journey

U sually, nine months after meeting someone, interviewing them and writing about them for the newspaper, you would expect one or two details of the encounter to stay alive in your mind. But my recollection of the day in late February that I visited Jan Morris at her home in north-west Wales is not like that. Every moment remains vivid.

Perhaps, you might say, this is because my pre-lockdown journey there – driving through Snowdonia on a wild, windy morning and down to the sea at Criccieth – was just about the only travelling I’ve done all year. But I don’t believe it is that. As anyone knows who ever made that journey to visit her at home, or who ever opened any of her 40 books, Morris dealt in adventure. Having packed her life brim full of extraordinary journeys, pilgrimages and quests, she knew exactly how to conjure their contours for others.

On Friday, her son Twm, a celebrated poet who writes in Welsh, and has a cottage across the road from hers, announced her death, at 94, in fitting bardic terms: “This morning at 11.40 at Ysbyty Bryn Beryl, on the Llyn, the author and traveller Jan Morris began her greatest journey. She leaves behind on the shore her lifelong partner, Elizabeth.”

When we met, in the promise of spring, part of Morris’s always cheerful talk was about that last journey. Elizabeth, who said hello from her bedroom, had for some years been suffering with dementia. Morris feared her own mind was failing, though there was scant evidence of that in her conversation. While we drank tea and talked in the long beamed sitting room, like the creaking cabin of a tall ship, a small fluttering bird tapped its beak on the window from time to time as if to gain entry. “Do you hear the bird tapping?” Morris asked. “It used to portend death, didn’t it? We have it every day at different windows.”

If she had a sense, as she said, that she was “at the very end of things”, she had not forgotten any of the steps that had brought her there. And what a journey! Morris, at 26, was the only journalist to accompany Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay on their 1953 ascent of Everest, and broke the story in the Times on Coronation Day. At other times, she wrote about living on Field Marshal Montgomery’s family houseboat on the Nile, and in a palazzo on the Grand Canal in Venice. She retained just a vestige of the journalist’s one-upmanship. Pointing at a picture of the 22,000ft Everest camp she reached, she said “That wasn’t a bad story, was it?”

When I got back from that day in Wales, I filled in gaps of books of Morris’s I hadn’t read and, in lockdown, I listened to the audio versions of some of those I had. These included her towering trilogy about the British empire, Pax Britannica , and Conundrum , a personal odyssey that began with her understanding aged “three or perhaps four … that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl” and ended with years of hormone treatment and pioneering gender reassignment surgery in Casablanca in 1972.

Of all the perilous journeys she had made in her life, that biological one seemed almost of least interest to her when we met, though she corrected something I said at one point. “I should say I would never use the word change, as in ‘sex-change’, for what happened to me. I did not change sex; I really absorbed one into the other. I’m a bit of each now. I freely admit it… But that’s all in that book I wrote, isn’t it?”

One consequence of what she called her “at-one-ment” was that she and Elizabeth had to divorce, though they continued to live together and keep a home for their children. When it became possible, Jan and Elizabeth reaffirmed their bond in a civil union ceremony in nearby Pwllheli in 2008, witnessed by a local couple who invited them to tea at their house afterwards.

That union will persist. When we met, Morris mentioned how they owned a small island on the Dwyfor river, which flows by their house. When the time came, their ashes would be scattered there together, and the place marked with a slate headstone – currently in a cupboard under the stairs – reading: “Here lie two friends, at the end of one life”.

The idea of eternal rest held little appeal for Morris’s roving soul. In one fantasy, she imagined a posthumous affair with a 19th-century admiral, Jack Fisher; and in her most haunted book, about the city of Trieste , she pictured another eternity beneath its seashore castle which sounds about perfect. “Most of the after-time, I shall be wandering with my beloved along the banks of the Dwyfor: but now and then you may find me in a boat below the walls of Miramar, watching the nightingales swarm.”

- The Observer

- Travel writing

- Transgender

- History books

Most viewed

Jan Morris, ground-breaking travel writer, dies at 94

Nov 21, 2020 • 3 min read

Welsh author Jan Morris pictured at the 1998 Hay Festival Hay on Wye Powys, Wales © Jeff Morgan 13 / Alamy Stock Photo

Jan Morris passed away on Friday morning at Ysbyty Bryn Beryl, a Welsh hospital on the the Llŷn Peninsula, at the age of 94. Born in 1926 in Somerset, her storied career started with a stint at the Western Daily Press in Bristol before she joined the army and served in World War II as an intelligence officer in Palestine and Trieste, Italy. After the war, Morris worked for The Times as a sub editor and two years later was sent on the assignment of a lifetime to cover the summit of Mt. Everest achieved by Colonel John Hunt, Tenzing Norgay, and Edmund Hillary in 1953.

Those early experiences were the foundation of a prolific and influential career as a journalist and author. Morris covered destinations from Hong Kong to Oman, Sydney to the South Africa in dozens of magazine and newspaper features, as well as books that spanned travel, history, biography, and memoir. One of her first full-length works was Coast to Coast, a family travelogue of the United States at the height of its post-war glitter. Morris spent much of the 1970s writing and publishing The Pax Britannica Trilogy, an exhaustive history of the British empire – indeed, her travels and nationality gave her a bird's eye view of the dawn of the post-colonial era. Even Morris's fiction was steeped in place, in particular Last Letters from Hav and Return to Hav – a pair of short post-modern novellas that fictionalized some of her long-term observations about the Middle East and cast them through the lens of science fiction. Last Letters was short listed for the 1985 Booker Prize.

Despite her success with travel writing and numerous awards, Morris often chafed at categorization , uncomfortable with the confines of genre or even the idea that she was strictly a place-based writer. In a 1989 interview with The Paris Review she observed, "I resist the idea that travel writing has got to be factual. I believe in its imaginative qualities and its potential as art and literature. ...I think of myself more as a belletrist, an old-fashioned word. Essayist would do; people understand that more or less. I believe my best books to be more historical than topographical."

Twenty years into her career, in 1972, Jan Morris traveled to Casablanca, Morocco for gender affirming surgery and ceased to use the male given name James personally or professionally. She published a book about her transition in 1974, noting that she had felt since she was a small child that she had been born in the wrong body. “I no longer feel isolated and unreal," she wrote. "Not only can I imagine more vividly how other people feel: released at last from those old bridles and blinkers, I am beginning to know how I feel myself.” Though she was forced to legally divorce her wife upon returning from Morocco – same-sex partnerships not being legal in the UK at the time – Morris and her wife Elizabeth were able to obtain a civil union in 2008. Their marriage lasted the rest of Morris's life, and spanned 71 years.

Morris never retired from writing; she published her final book, Thinking Again , in March of 2020. It collects a series of daily diary entries penned between 2018 and 2019, which range from personal reminiscences to reflections on Welsh nationalism and current affairs like Brexit. Though she was by then sticking close to her home in Llanystumdwy, Morris's final work still conveys a deep and abiding passion for people and place and the acute observations that drew many to her oeuvre. But her legacy is broader and deeper than her writings, encompassing nationality and identity as well. She will be remembered not just as an author, but also as a pioneer for women – and particularly trans women – both in travel and in publishing. Indeed, what Morris once said of libraries could well be said of her life – "Book lovers will understand me, and they will know too that part of the pleasure of a library lies in its very existence.”

Explore related stories

Art and Culture

Dec 6, 2021 • 6 min read

Curling up with a book this winter? London's beautiful, unique bookshops are the perfect place to pick one up.

Nov 22, 2021 • 5 min read

Nov 19, 2020 • 7 min read

May 11, 2024 • 11 min read

May 12, 2024 • 9 min read

May 11, 2024 • 9 min read

May 10, 2024 • 9 min read

May 10, 2024 • 5 min read

May 9, 2024 • 9 min read

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Jan Morris Talks Travel, Dictionaries, and Other People’s Diaries

Paul clements in conversation with the late, great travel writer.

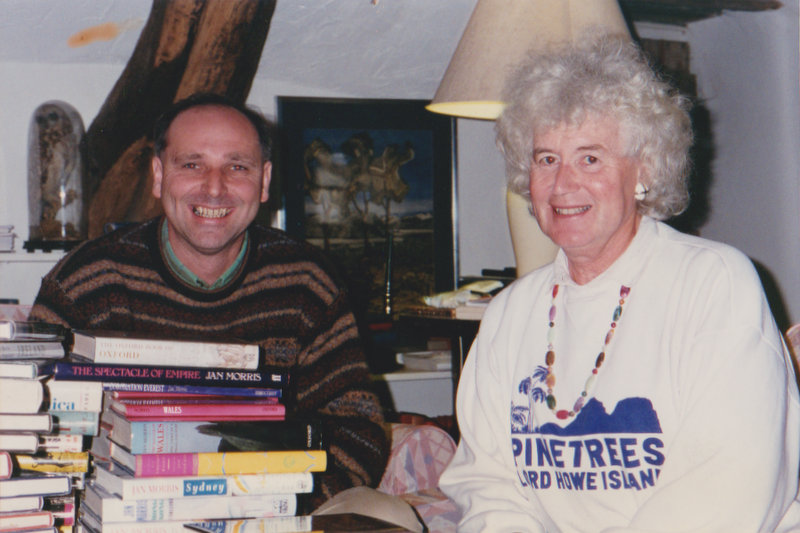

When I interviewed Jan Morris about her extensive book collection running to more than 8,000 titles, I had known her personally for seven years, had been familiar with her writing for more than two decades, and written a monograph on her in the “Writers of Wales” series. She agreed to what turned out to be a lengthy interview about the books that inspired her and those that she often re-visited and cherished or were in some way special.

The interview ran in The Book and Magazine Collector (issue No. 200, November 2000), a monthly magazine published in London from 1984-2010. It was carried out at Morris’s house, Trefan Morys, in the northwest corner of Wales where the family had moved to live in 1965. After the interview, in her usual generous manner, Morris’s wife Elizabeth served bara brith fruit loaf, Welsh cheese and coffee.

For agreeing to be interviewed and giving off her time, I brought Jan a bottle of red Barolo wine, and told her it was known as the “Wine of Kings and the King of Wines.” She telephoned me later to thank me and said that they enjoyed the full-bodied Barolo and now felt “quite noble.” It was an important interview to carry out for the historical and literary record, and I later drew on material from it for my biography: Jan Morris, Life from Both Sides , published by Scribe in 2022 .

Which books did you read as a child? The first book which I consciously remember reading was the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn . I like water, and the book had a great sense of adventure. The language was strange to me as it was American, so it was very exotic. It was my grandfather’s Chatto & Windus edition, which I still have. It wasn’t the first book I read because it was quite difficult to read, but it was the first I remember.

What other children’s books did you read? I also read Alice in Wonderland , which is a great book. I didn’t really like children’s books, but I enjoyed what you might call “grown-up” children’s books like Alice.

Were there always books in your house when you were growing up? My mother read a lot and there were always books lying around the house, so they played an extremely important part in my early life.

You have a huge collection. Could we begin with your travel books, which seem to form a large section? To tell you the truth, I don’t believe in travel books as such, because I feel they all blur into each other. I call them “place books”, because they are books about places. The biggest segment is probably my guidebooks which I use chiefly for reference, although one or two are obviously works of art in their own right. I especially like Murray’s Handbook for Spain by Richard Ford, which is the best book about the country. My copy is a reprint of the original edition, which came out in 1845. He was a racy, exuberant and uninhibited traveler who was often rude because he didn’t care for anybody’s opinion.

What else do you like about old guidebooks—is it the atmosphere they conjure up? Partly that, but I also like the look of them as objects. They are nice to hold and to own, and as they get older, for me, they get quainter and more interesting. They also take you to another time, another place and back into the company of something long gone.

I notice you have a run of the legendary Baedeker guides? I use the Baedekers constantly and especially when I am traveling, even if they are out of date. At the moment, I am writing about Trieste and one of the most useful books to me has been the Austria-Hungary Baedeker of 1905. It includes Dalmatia and Bosnia and describes the whole of Austria-Hungary at the turn of the century. So I would never get rid of my Baedekers for anything.

You have a big collection of new guidebooks as well. Which do you like best? I find the Lonely Planet and Rough Guides very useful. I have some of the colorful Insight guides, as well as Michelin, Blue Guides, Pallas Guides, and the rather posher ones like Everyman Guides to cities, which are lavishly illustrated. I also have a lovely collection of the Companion Guides to countries and cities which were published by Collins in the seventies and eighties.

What is the rarest item amongst your travel books? It would probably be some of my old books of Arabian travel. I have a copy of Sir Richard Burton’s Pilgrimage to El-Medinah and Meccah . It’s a first edition in three volumes, published in 1855. It’s a beautifully produced book, with colored endpapers, and was presented to me by a friend, which was rather rash of him. I suppose it is a rare and valuable book, although I have no idea how much it is worth. Apart from that it is a very good book which you could read equally well in paperback.

Which book has meant most to you during your writing and traveling life? Travels in Arabia Deserts by Charles Doughty. It is a magical book and I have several copies of it. The first one is an American one-volume edition which I bought from Steimatsky’s in Jerusalem in 1947. I love the smell of it, and the feel of it, and the book for itself. I also bought the 1936 Jonathan Cape edition in two volumes and a condensed two-volume edition called Wanderings in Arabia which is inscribed by Doughty.

You’ve just sniffed that book—what do you get from that? Yes, I am a book-sniffer, although I don’t know where the habit came from. Even after these years, I can still smell the Random House ink off the pages. The smell is only now fading. Some people sniff drugs and glue, but I sniff books—it’s just something I’ve always done.

Do you always write your name in every book you buy? All my life I’ve written my name and the date and place of purchase in non-fiction books, and I have generally preserved the bookseller’s penciled price. I sometimes write other comments about the book on the title-page.

Which book has been your happiest find or the one that you were most pleased to get? I don’t regard myself as a book collector as such, although I have bought books all over the world. When I was in Cairo in the 1950s, I found a copy of E.M. Forester’s Alexandria in a bookshop. Almost the entire original 1922 edition was destroyed in a warehouse fire, but I managed to get a copy of the replacement edition published by the Royal Archaeological Society of Alexandria in 1932 and signed by Forester. I have always admired and followed his advice about seeing the city: “the best way is to wander aimlessly about.”

W hich travel book means the most to you? Eothen by Alexander Kinglake, which was given to me as a present many years ago and which I cherish more than any other book. I have several copies, including the first edition published in 1844 and the sumptuous edition which Frank Brangwyn illustrated.

What’s so special about Eothen? It suits me, that’s what’s so special about it. It is detached, wry, ironical, charming and quite frankly, elitist, and in every way I’m fond of it and I like him. It is one of the most original and creative of all travel books. It has had long innings—the first edition was published anonymously and it has been reprinted many times since then. In 1982, I wrote the introduction to the Oxford University Press paperback edition.

What about books on specific countries and cities? The writer, Gerald Brenan, who wrote books about Spain, once gave me some books as a souvenir of my visit to the country, so I built up a good library of Spanish books. I wrote a book about Spain in the sixties but I haven’t kept up with buying books about it. Brenan also gave me some Arabian books of travel, including the eighteenth century topographical account of the region, Neibuhr’s Travels Through Arabia.

Why did he give them to you? I think he thought he was getting old and was going to die and he wanted them to go to someone who would appreciate them, which I certainly have.

I see that you have a large section on the United States. I’m fascinated by the United States and have visited every year since my first trip in 1953. I have written several books about America, including two about New York, so I have a good collection of books about the city. One of my favorites came out just last year— Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 , written by Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace. Others look at specific areas such as the port of New York and the harbor.

As regards to other books about the U.S., I have a good selection of Works Projects Guides which were published between the wars, and a selection of guide books covering most of the different states of the Union. In 1999, I published a book about Abraham Lincoln. I wanted to read as much about him as I could find and ended up with a large collection of books about his life—apparently thre are ten thousand biographies of Lincoln.

What other countries are represented in your collection? I once bought a lot of books about Afghanistan because I was going to write about the first Afghan War—the retreat from Kabul—and I invested in a lot of books. I bought all I could find, but in the end it boiled down to a chapter in my book, Pax Britannica, the trilogy about the rise and decline of the British Empire. But I have kept those books as I’m very fond of them. They are quite rare and I suppose quite valuable.

You have written your own account of the 1953 Everest expedition, and you have a veritable mountain of books, if you’ll pardon the pun, about Everest. As the Times correspondent, I accompanied the British expedition party led by Sir John Hunt that conquered Everest in 1953. The expedition spawned a large number of books. But prior to that, many accounts were written of individual expeditions by climbers. There are more than forty works in total from the official Everest expeditions between 1921 and 1953, and I have them all.

Do you have a favorite? I’ve got a copy of W.H. Murray’s book The Story of Everest , which is a general history of the climbs published in 1953. It was signed on the spot by all the climbers in the party. It was a proof copy that I brought with me, and everybody naturally was interested in it because it hadn’t been published. So they all read it while we were on the mountain and I got all the members of the expedition, including Sherpa Tenzing who could hardly write, to sign it.

You can see that it comes complete with tea-stains and grubby finger-prints, which give it authenticity. After 1953, I lost interest in Everest, although I have written articles about it and recently reviewed for The Spectator Sir Edmund Hillary’s book, View from the Summit , and a new book on George Mallory.

You have an interest in architecture and were recently appointed an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects? I have quite a large number of books on Islamic architecture, which has been a particular interest of mine. There’s also a complete run of the Nikolaus Pevsner “Building of England and Wales” architectural guides, of which I am rather proud. The trouble is that, along with the large-format art books, they do take up a large amount of shelf space.

I see that you have removed the dust jackets from your Pevsners. Why is that? It all goes back to my Oxford days when I was an undergraduate at Christ Church. My tutor there was J.I.M. Stewert, who was the author of donnish detective stories under the pseudonym “Michael Innes.” When a new book arrived, he immediately threw away the jacket and I thought this was rather stylish so for a time I did the same, but I don’t do it now and I wish I’d kept them.

Could you tell me about your reference books and dictionaries? I do love dictionaries. I have a fairly big section of reference books, which includes a whole batch of foreign-language dictionaries. I like words very much and I like to be able to look up what people have said about language. One special item is the two-volume edition of Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language . One of my children picked off some bits of the binding but it’s still in remarkably good condition considering that this edition, which is the fifth, was published in 1784.

It is superbly produced with gilt edging, and was given to me by one of my brothers in 1953 as a souvenir of climbing Everest. I have used it widely over the years and often use it still. Now, thanks to CD-Rom, I have some of these reference books on disc rather than in book-form, and sometimes both.

I see some atlases in this part of your library, too. There are quite a few new atlases and some historical atlases. I have every edition of the Times Atlas of the World since it was first published, including the grand five-volume set which is called the mid-century edition—a name, incidentally, which I gave it.

Do you like reading other people’s diaries? I’ve got all sorts of diaries and journals. Some are literary and theatrical—Alec Guinness, Harold Nicolson, Virginia Woolf, Noel Coward, which I thought was very contrived but they certainly give the impression of having been jotted down, and I like that. I do like the immediacy of people’s diaries.

What about general English and European literature? I keep the fiction side in a separate area. It covers a wide spectrum of nineteenth and twentieth-century authors. Some, like Kipling, I’ve got in pretty well complete editions. Other authors include Trollope, Joseph Conrad, James Joyce, Oscar Wilde, Evelyn Waugh, Graham Greene, plus many European writers. I have quite a lot of Balzac, Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Proust.

I have always loved Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina and have my grandfather’s copy in the old Constance Garnett edition, which is quaint and which I like very much. Recently in the United States, I bought the Everyman edition, which was published by Knopf. It is a nice copy, but I don’t like it as much as the old Constance Garnett one!

Moving to another section of your library, there is a collection of books about Wales. You have written widely about Wales and you are passionate about it. What’s in your Welsh collection? It’s quite a ragbag collection. It’s mostly made up of history, literature, travel, topography, art and architecture—everything from the standard History of Wales by John Davies to the Shell Guide to Wales with a gazetteer by Alun Llewellyn and a splendid historical introduction by Wynford Vaughan-Thomas. The literature section includes some classic works by the medieval poet, Dafydd ap Gwilym, the great Welsh storyteller, Kate Roberts, and the poet, R.S. Thomas. I also try to read most of the present-day novelists like Robin Llewellyn.

I also see a collection of slim books with white covers about Welsh writers. What are they? They are the “Writers of Wales” series of monographs which feature Welsh and Anglo-Welsh poets, novelists and writers. It’s a very worthwhile series published by the University of Wales Press in Cardiff and provides a critical introduction to Welsh writers. In fact, the series is the longest in the history of Welsh publishing and has been in existence for nearly thirty years. I like supporting Welsh publishers such as Seren and Gomer who are doing a very good job with their books. I review their books whenever I can, but they rarely get the recognition of the London papers.

What is the stack of magazines on the window ledge beside the Welsh books? That’s a large run of Planet: The Welsh Internationalist , which is a bimontly magazine. It covers all sorts of topics, including politics, art, music, literature, and the environment, and has a good review section. I’ve also got an almost complete collection of the Transactions of the Society of Cymmrodorion —a cultural and patriotic society founded in 1751—which still appear annually. There are so many of them that I have to store half of them at my son’s house.

Staying with the Welsh theme, do you ever visit Hay-on-Wye to buy books? I have bought books there but I don’t like it, although some of the shops are good. I don’t like seeing an old country town turned into a place for one type of shopping only. Having said that, I am a great supporter and advocate of the Hay Festival and have spoken at it on occasions.

Elsewhere in the world do you have any favorite bookshops that you always revisit? Unfortunately, many of my favorite bookshops have closed. I used to go to the Tillman Place Bookstore in San Francisco, which had a mix of secondhand and new books, but has recently closed. There were also some in New York, although I can’t remember their names. They were single-owner bookshops with very good selections.

Are there any other subject areas in which you have become interested? Lately, I’ve been buying more and more books by continental authors. For example, I have tried to get all Joseph Roth’s books. He wrote about the Austrian Empire and there’s presently a major republication of his work. Some of his books are only being published for the first time now, even though he died in 1939.

Are there any major gaps in your collection? I am weak on science fiction. I never got into it and I regret it in a way because I realize that there is more to it than I used to think. I have got a few War of the Worlds -type books, but I have never really explored the field thoroughly enough.

If there was a fire in your house and you could rescue only one book, which one would it be? After the cat—of course—I’d go for him first—it would be Eothen, largely for sentimental reasons.

Finally, which three books would you take with you to a desert island? Firstly, Doughty’s Arabia Deserts . Then War and Peace and I think, a P.G. Wodehouse—perhaps a “Jeeves” book for the charm of the writing.

__________________________________

Jan Morris: Life from Both Sides by Paul Clements is available via Scribe.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Paul Clements

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

The Optimistic, Expansive Visions of Pregnancy and Motherhood in the 1962 Novel Memoirs of a Spacewoman

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- Nation & World

Jan Morris, artful travel writer who broke many boundaries, dies at 94

As a young reporter, Jan Morris was on the mountainside, at 22,000 feet, when the first expedition in history reached the top of Mount Everest. She reported on wars and revolutions around the globe, published dozens of elegant books exploring far-flung places and times and was regarded as perhaps the greatest travel writer of her time.

Yet the most remarkable journey of her life was across a private border, when she cast off her earlier identity as James Morris and became Jan Morris.

A writer of extraordinary range and productivity, and one of the world’s first well-known transgender public figures, Morris was 94 when she died Nov. 20 at a hospital in the Welsh town of Pwllheli. Her son Twm Morys announced the death in a statement but did not state the cause.

Jan Morris spent her first 45 years as James Morris, who had been a British cavalry officer, a World War II veteran and a dashing reporter renowned for international adventures and evocative writing.

“On the face of things,” a onetime colleague, David Holden, wrote in 1974, “a less likely candidate for a sex change than James Morris would have been hard to imagine. His whole career and reputation had created an aura of glamorous and successful masculinity.”

In the 1940s, James Morris lived on the Nile on the houseboat of British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery. In 1953, never having climbed a mountain before, James joined the expedition of Sir Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay and came within 7,000 feet of the summit of Mount Everest, the world’s highest peak. Scrambling back down, James delivered the news that Everest had been conquered for the first time in history. The Times of London printed the story on the eve of the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

“I went up an unknown,” Morris told the New York Times in 1997, “and came down the most famous journalist in the world.”

Constantly on the move, James Morris reported from Israel, Algeria, South Africa and Japan, primarily for British newspapers and magazines, published books and was praised by New York Times critic Orville Prescott as a “poet and a phrase-maker with a fine flair for the beauties of the English language.”

James Morris covered the Moscow show trial of U.S. spy plane pilot Francis Gary Powers and the trial in Jerusalem of unrepentant Nazi henchman Adolf Eichmann. In Cuba, James interviewed the charismatic revolutionary Che Guevara and in a 1960 dispatch published in the New York Times offered a grim assessment of what the future would hold for the country under Fidel Castro.”

“It is a strikingly immature regime – not just in age but in style and judgment too. The rulers of Havana reduce all things to simple right or wrong, East or West, in or out, yours or ours. There still is good in many of their notions, a surviving streak of idealism, a genuine quality of young inspiration. But there is little subtlety, no experience, and scarcely a jot of that prime political commodity, irony.”

In 1960, James Morris published the best-selling “Venice” (called “The World of Venice” in the United States), creating a distinctive style of travel writing, a literary dreamscape evoking past and present at once, as sensory impressions and a poignant awareness of what some called the “psychology of place” were threaded into an elegant, flowing prose.

Venice – for centuries an independent republic before it became part of Italy – “was something unique among the nations, half eastern, half western, half land, half sea, poised between Rome and Byzantium, between Christianity and Islam, one foot in Europe, the other paddling in the pearls of Asia. She . . . even had her own calendar, in which the year began on March 1st, and the days began in the evening.”

Other books followed, about New York, Britain, South America and Spain, as well as an ambitious three-volume history of the British Empire that was so authoritatively written that critics were reminded of Edward Gibbon’s monumental 18th-century chronicle of ancient Rome.

James Morris had public acclaim and a seemingly contented family life as the married father of four children – but there remained a central, inescapable fact: a misaligned gender identity, “a life distorted.”

“I was three or perhaps four years old,” Jan Morris wrote in her first book under that name, the autobiographical “Conundrum” (1974), “when I realized that I had been born into the wrong body, and should really be a girl. I remember the moment well” – sitting under the piano, while her mother played Sibelius – “and it is the earliest memory of my life.”

Before marrying Elizabeth Tuckniss in 1949, James Morris explained this sense of inner conflict, telling her that “each year my every instinct seemed to become more feminine, my entombment within the male physique more terrible to me.”

James Morris began hormone treatments in 1964 and consulted with Harry Benjamin, an American physician and the author of “The Transsexual Phenomenon” (1966). In 1972, James went to Casablanca for transition surgery, choosing a doctor experienced in the procedure.

Two weeks later, Jan Morris flew back to England, where she was greeted by Elizabeth. Under British law at the time, they had to obtain a divorce because same-sex couples were not permitted to marry. Still, they continued to live together.

“To me gender is not physical at all, but is altogether insubstantial,” Morris wrote in “Conundrum,” which became an international best seller. “It is the essentialness of oneself, the psyche, the fragment of unity. Male and female are sex, masculine and feminine are gender, and though the conceptions obviously overlap, they are far from synonymous.”

Many readers admired Morris’s revelatory candor, but others were confused or hostile. In Esquire magazine, Nora Ephron disparaged “Conundrum” as “a mawkish and embarrassing book. . . . Jan Morris is perfectly awful at being a woman; what she has become instead is exactly what James Morris wanted to become those many years ago. A girl. And worse, a 47-year-old girl.”

In any case, Morris continued with her writing life much as before, only wearing skirts, necklaces, a nimbus of graying hair and a perpetual smile.

Most Read Nation & World Stories

- Sports on TV & radio: Local listings for Seattle games and events

- Hillary Clinton accuses protesters of ignorance of Mideast history

- There are 2 new, highly transmissible COVID-19 variants collectively known as FLiRT

- Trump may owe $100 million from double-dip tax breaks, audit shows

- Thomas says critics are pushing ‘nastiness’ and calls Washington a ‘hideous place’

She completed the final volume of the British Empire trilogy and continued to wander the globe, writing for Rolling Stone and other publications. The books seem to pour out of her, often with simple titles such as “Travels,” “Journeys,” “Destinations” and “Among the Cities.”

She became almost a revered figure, considered a founder of modern travel writing, even though she resisted the title.

“The reason why I don’t regard myself as a travel writer is that the books have never tried to tell somebody what a city is like,” she told the Independent in 2001. “All I do is say how I’ve felt about it, how it impinged on my sensibility.”

Morris was often asked which city in the world, out of the hundreds she knew, was her favorite. She invariably named Manhattan and Venice, both of which she visited every year.

But she also had an abiding attachment to Trieste, a somewhat eccentric port city in northeastern Italy. Morris first saw Trieste in 1945, then returned periodically over the years before publishing in 2001 what she considered perhaps her finest travel book, “Trieste and the Meaning of Nowhere.”

“The nostalgia that I felt here 50 years ago was, I realize now, nostalgia not for a lost Europe, but for a Europe that never was, and has yet to be,” she wrote. “But we can still hope and try, and be grateful that we are where we are, in this ever-marvelous and fateful corner of the world.”

James Humphry Morris was born Oct. 2, 1926, in Clevedon, England.

At 17, James Morris joined the 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers, a storied British cavalry unit, and served in Italy and the Middle East during World War II. James later worked for a news agency in Cairo, then returned to Britain to study at the University of Oxford, graduating in 1951.

After working for the Times of London for several years, James joined what was then the Manchester Guardian in 1956 as “wandering correspondent,” winning a George Polk Award for journalism in 1960. A year later, James became a freelance writer and received a master’s degree in English literature from Oxford.

It was in Oxford where James Morris made the first tentative steps toward becoming Jan, going out in public wearing dresses and makeup, years before athletes Renée Richards and Caitlyn Jenner were heralded as transgender pioneers.

In 2008, Morris and Elizabeth Tuckniss Morris were united in a civil union.

“I made my marriage vows 59 years ago and still have them,” Elizabeth Morris told Britain’s Evening Standard. “We are back together again officially. After Jan had a sex change we had to divorce. So there we were. It did not make any difference to me. We still had our family. We just carried on.”

They settled in the Welsh village of Llanystumdwy, with one of their sons living next door. The couple arranged for a joint gravestone with an engraving in Welsh and English: “Here are two friends, at the end of one life.”

In addition to Elizabeth Morris and their son, Twm Morys, survivors include three other children. Another child, a daughter, died in infancy.

If anything, Jan Morris was a more productive writer than James had been. She often published two or three books a year, and more than 45 in all. Besides her accounts of travel, history and autobiography, she wrote two novels and biographical studies of Abraham Lincoln and British admiral John Fisher.

In 2018, she published “Battleship Yamato,” about an ill-fated Japanese warship that was sunk in 1945. It was believed to be one of the last books about World War II written by a veteran of the war. She continued to publish essays about her life in Wales, her memories and what she called the “tangled web” of her life until shortly before her death.

“I spent half my life traveling in foreign places,” Morris wrote in “Conundrum.” “I did it because I liked it, and to earn a living, and I have only lately recognized that incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey.”

Venice and Morris and Me

One writer travels to “la serenissima” and finds that time is no match for venice’s magic..

- Copy Link copied

Jan Morris first arrived in Venice in 1945, as an 18-year-old intelligence officer with the British Army. Then she was James Morris: a man to the world, a woman to herself.

Photo by Linda Heimerman

I am in Venice, in search of Jan Morris, the great British travel writer and historian who died last November at the age of 94. I am here with my younger sister, Virginia, who has gamely agreed to a Morris-inspired itinerary. Our guidebook is not Fodor’s or Lonely Planet but Morris’s own The World of Venice , published in 1960 and still in print today. It is a rhapsodic book, zesty and beguiling, about this “lonely hauteur,” this “jumbled, higgledy-piggledy mass,” this “God-built city”: Venezia. Here, “all feels light, spacious, carefree, crystalline,” Morris writes with characteristic aplomb, “as though the decorators of the city had mixed their paints in champagne, and the masons laced their mortar with lavender.”

I first encountered Morris’s singular, celebratory prose in graduate school. Smitten, I hurled myself into her published work—a vast collection of more than 50 books, most of them about place. Morris, I learned, was promiscuous in her affections, finding something to love virtually everywhere she went. And yet there was one locale that seduced her with particular intensity: an island city that would prove fodder for no fewer than four books and scores of articles and essays. Writing of this brackish wonder in her 1974 memoir Conundrum , Morris recalls “trailing my fingers in the muddy water, submitting to what I still think to have been the most truly libidinous of a lifetime’s varied indulgences—the lust of Venice.” With an endorsement like that, how could I stay away?

On disembarking from a water taxi, Virginia and I locate our bed-and-breakfast along a meter-wide alleyway in the central San Marco district. The proprietor, Elisabetta, leads us up to the top-floor apartment where we’ll be staying for the next several days. She says she’s sorry if she seems sluggish: She has only just received her second vaccine shot and is feeling its effects. I ask about her experience of the pandemic, and for several minutes we swap COVID stories. During lockdown, she says, she was allowed no more than 400 meters from her house. It is July 2021: This is how strangers make small talk.

Out in the city, Virginia and I wander. It is our first time here, and we share an almost petulant astonishment at the sheer fact of the place. The borderlessness between the canals and the buildings is as beautiful as it is ridiculous: Could the city founders have chosen a less practical place to establish themselves? There are no cars, of course, and the row houses look like something out of Renaissance science fiction, as if they’d emerged fully formed from the muck beneath. This is Venice, then—all storybook bridges, striped-shirt gondoliers, and pigeon-filled campos. A city more or less happily acclimated to a permanent flood.

Jan Morris first arrived here in 1945, as an 18-year-old intelligence officer with the British Army. Then she was James Morris: a man to the world, a woman to herself. ( Editor’s note: Morris wouldn’t transition for another three decades, but we are using her preferred pronouns throughout.) Venice was in those days like “a surrendered knight at arms”—a wistful, melancholic place where the glories of the old republic, the so-called Serenissima, had been ceded to a decidedly humbler present.

In the late 1950s, Morris returned with her young family to write a book about the island. For a year they lived in a flat near the Grand Canal, the city’s main thoroughfare and waterway, “in a condition of more or less constant ecstasy.” This was the year that led to The World of Venice , Morris’s most famous book and the one that would make her most widely known. Not that she was a nobody: In 1953, at the age of 26, she’d reported the news of Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary’s successful ascent of Everest, gleefully sprinting down the ice-choked Western Cwm with one of the great journalistic scoops of the century.

After lunch, Virginia peels off to take a nap. I wander east, passing shop windows full of court masks, quill pens, and tiny glass animals. I shake my head “no” at gondoliers asking if I want a ride, and marvel at the uncrowded squares, appreciating my luck, to be meeting the city at its least crowded in perhaps decades. Venice is hardly empty, but it certainly isn’t full, either: When I walk into a stationery shop or take a seat on a bench, there’s almost no one competing for space—hardly the experience of the estimated 20 to 27 million visitors who crammed here annually in the years before the pandemic. (In The World of Venice , Morris reports that “rather more than 700,000 foreigners came to Venice in a normal recent year.”)

The sky above is a chalky fresco blue. I continue east, soon arriving at the Public Garden, a rare stretch of Venetian greenery where the cicadas buzz in hypnotic syncopation. Along the water I locate the statue of Italian nationalist Guglielmo Oberdan, his acid-stained visage trained out on the lagoon. I pull out my book, flipping to a passage Morris wrote about this very spot. Then I call out an odd, childish sound—“ chwirk, chwirk ”—waiting to see if the invocation will summon a passel of cats, as Morris has promised it will. But there is no movement in the dense shrubbery surrounding the statue, and when I peer deeper into the greenery, I see only a discarded white porcelain toilet bowl.

British writer and historian Jan Morris, pictured at her home near the village of Llanystumdwy, Wales, in 2007.

Photo by Colin McPherson

Morris would’ve surely chuckled at my attempts to follow , quite literally, in her footsteps. She conceived of her books as personal, impressionistic evocations, not “to do” lists for the intrepid tourist. It was for this reason, perhaps, that she always bristled at the moniker “travel writer.” She didn’t write about travel, she insisted. She wrote about place.

If Morris’s gleefully subjective mode of reportage seems commonplace today, it wasn’t always so. As historian Peter Stead put it in a BBC profile about Morris, the genre was once divided into two rather tedious camps, at least in Britain: the scholars on the one hand and the complainers on the other. The scholars wrote for a highly educated audience that understood oblique references to art and history. The complainers, conversely, used their forays away from home to point out the failings of others: Those Italian waiters—really!

Morris pursued a different path, churning out dozens of books in a distinctively brilliantine style as admiring as it was accessible. Most of her research was done in the streets, wandering around and asking for directions. One of her favorite tactics for diagnosing a city was something she called “The Smile Test,” wherein she grinned broadly at locals, using their responses to gauge the character of a place. (In 2013, she told journalist Don George that San Francisco passed the test best of anywhere and was thus the most open-hearted city on Earth.)

Continuing onward, I try “The Smile Test” for myself, beaming stupidly at an old woman with her dog; at a man with a black-ribboned straw hat; at a group of 20-somethings in dark Puma gear. The results are inconclusive: No one really seems to notice me, or else they’re all too accustomed to idiot foreigners like myself to bother reacting.

By now I have made my way to the northern side of Venice, where the streets are mostly empty and the boats are all shrouded in tan and blue canvas covers. Despite the quiet, I see evidence of life hanging on the clotheslines that stretch from building to building, their damp carriage lolling gently in the breeze. I love these displays not just for their quaintness but also for their startling vulnerability. In one alleyway I spot a pink bra and an elastic-waisted pair of flower-print pants. In another, I glimpse a Nirvana T-shirt and a pair of polo shirts whose sweat stains are visible on their collars.